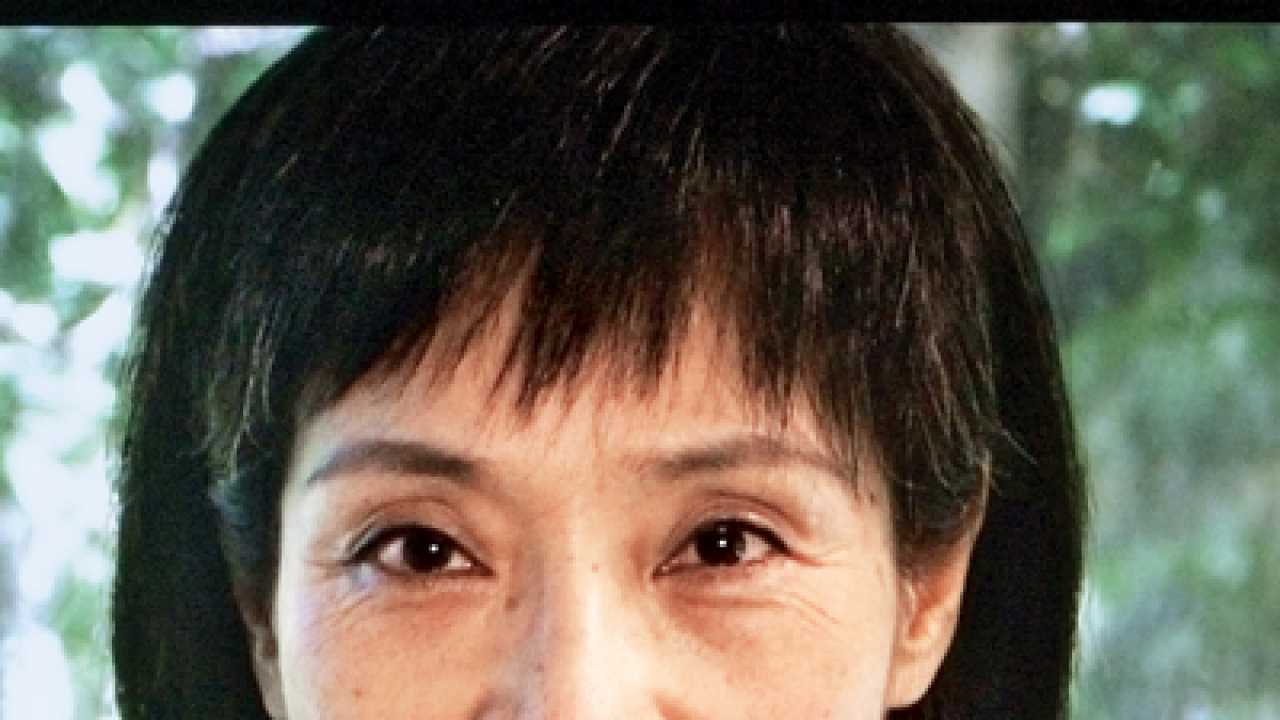

Anchee Min was 17 when was sent to work in China's infamous collective farms, after which she was made a propaganda artist. Her memoir, Red Azalea, is a frank and candid confession of an extraordinary life. Between pages of description of the guilt of having to denounce a favourite teacher, the perplexing emotion of not making your mother proud, the drudgery of 15-hour work days toiling at collective farms and the fear of watching your escape plan come to naught, lies a vivid and gripping account of life in China during the decade-long Cultural Revolution.

The second part of her memoir, The Cooked Seed is a classic narrative of an immigrant's life in America: Not speaking English, falling down, getting hurt, standing up again, finding your bearings and making a success of life; In Anchee's case, by writing several books on some of China's most incredible women in some of China's most incredible circumstances.

What are your earliest memories of your childhood and of your family?

My mother (once) came to pick me up from kindergarten in day light. She was wearing a mask, and was very happy that she was allowed a leave work early. Her tuberculosis was so bad that it was contagious and she was kicked out.

You went through a lot of harsh experiences (denouncing your teacher, toiling in collective farms) at a tender age. Do you recall being particularly puzzled, tormented about something, or having conflicting feelings and thoughts? Can you elaborate.

During China's Cultural Revolution, the entire society was forced to think one thought — loyalty to Mao. We operated on fear and fear alone. If you didn't do what was told, punishment would follow. The only thing that puzzled me was that my mother was not proud of my award-certificate, which I brought to her. She was displeased that I was praised by my school as the model student, 'Little Red Guard'. My mother was bothered that there were no children's books (that we were reading). She had trouble with the fact that Mao's books were our school text books, although she dared not voice her opinion.

You've been open about the fact that you were in a relationship with another woman during this time. Where do you think this stemmed from?

It was a craving for human connection. She was in love with a young man in another company, and was frustrated that she couldn't get in touch with him. I volunteered to play the go-between, and delivered their letters. When the man was afraid to reveal his feelings, and I returned empty-handed, I couldn't bear my friend's disappointment. I started to make up stories, telling her about how much he loved her. Eventually, I played her boyfriend and kissing followed naturally (inside the mosquito net). It was by such accident (that) I discovered the poetry of God, that love is limitless in its expressions and forms.

Were homosexual relationships common during the Cultural Revolution?

I have no idea. We were so very isolated. The punishment for sexual intimacy was severe. We had over a hundred thousand youth, in the age group of 17 to 25 working in the collective farms near the East China Sea. The only way to maintain control over human nature was through terror. Our youth was robbed.

You've said that you learnt to write 'I love Chairman Mao' before you learnt to write your own name. Did you ever question what the allegiance to Mao meant?

No. It never occurred to me to question it. We were taught and trained at a very young age to follow Mao's will, and to devote ourselves to our country.

When the scouts selected you as one of 'peasant faces,' did you think it would lead to a better life – away from the hours of toil at the farms? How did it eventually turn out?

I was spotted while hoeing weeds in a cotton field. I received a letter ordering me to report to the Shanghai Film Studio for a screen test. I saw hundreds of beautiful young women of my own age there. We competed. I dare not hope that I would be the one chosen as the face of "Proletarian China". Of course, I would've done anything to escape the labour camp. But there was no way to know (who would be selected). Everything depended on "orders" from upstairs, which meant Madam Mao. I turned out to be a lousy actress. I couldn't cry on cue. When the camera started to roll, my body trembled so badly that the camera assistant had to pin my costume down.

You worked in close proximity to Mao's wife, Jiang Qing or Madam Mao. Can you describe her?

We were sent to Beijing to watch Madam Mao's favourite Western movies to learn the technique of filmmaking. The movie was Jane Eyre and The Sound of Music. It surprised me that these were Madam Mao's favourite movies, for they were full of human emotions. I didn't have personal contact with Madam Mao, but people who did told me that she was quite a character, hysterical. She told everyone that she was Mao's "foot-soldier". She produced eight propaganda modern operas for a billion people to watch, to be brain-washed to worship Mao. She succeeded and the movies were an effective tool.

Upon your arrival in the US - at the airport - you were taken in by the softness and fragrance of toilet paper. What were the other small joys of life that you cherished in your initial years in the States? Apart from language, what were the cultural shocks you experienced.

Hot water in the shower and toilet, air-conditioned rooms, elevators and refrigerator. The smiling faces on women's magazines were a culture shock. I had never seen smiles like that — smiles that came from the heart and soul, and the faces that bore no mark of worrying or suffering.

You lived a tough life in China and a tough life as an immigrant in the US. What were some of the most valuable lessons you learnt during these years of struggle?

I learnt not to take anything for granted. There are bad apples in every society. There are also extraordinarily kind people. (it is important to) have gratitude and keep one's spirit up.

You went to the United States to study art. How did your writing career start?

Studying art was an excuse (to get to the US). I didn't speak English and I knew I wouldn't be able to survive without English. So I spend most of my time at art school working on my English. One day, my English teacher told me that I was "a lousy writer", but that I had "excellent material". I realised that I had something unique. (It occurred to me that) my 27 years of experience of living in China were "the wonderful material" that I could share with America and the world.

Apart from Madam Mao, you've written about many other Chinese women; powerful leaders and commoners. Which of these characters did you find most compelling as a writer and why?

I found Empress Orchid Ci Xi a compelling character. The interesting thing that historians never mentioned was her upbringing before she was selected as an Imperial consort and eventually became the empress. She grew up in China's poorest province, Anhui. She must have brought all those experiences and common-senses to the Forbidden City and ruled China from behind the curtain with such senses. The dynasty lasted for 50 years before she died. To a writer, such "gray area" is very meaty.

Which of your own books is your favourite?

Probably (the memoir books) Red Azalea and The Cooked Seed. It's my life, and I didn't have to research for them. For the other books, I had to spend years to do research to get every detail right.

Who are your favourite Chinese writers, or writers who write about China? Which of their works would you recommend?

My favourite writer who wrote about China is, still, Pearl S. Buck. Her understanding of China is superior. Among the Chinese language writers, I enjoyed (reading) Shi Tie-Sheng and Chi Li. Any of their works are good.

China has transformed dramatically in the last few decades — financially, politically and as a society. Is Beijing doing everything right — or terribly messing things up?

Beijing is trying its best. It's not easy to feed 1.3 billion people. It's so easy to point fingers and criticise. China's problem is a hidden one. The "aftermath" of the Cultural Revolution is what the nation is suffering (from). We lack immunity from capitalism and a profit-driven market. We want democracy, but we don't understand what democracy truly means. For example, it doesn't mean "take" but not "give". Freedom to Chinese peasants can mean the freedom to decide whether to add extra fertiliser to their plants, chemicals to their food and dump polluted waste water in the rivers.

What do you miss the most about the Middle Kingdom?

I miss Chinese folk songs and music. I also miss washing my dishes in the Yangtze River.