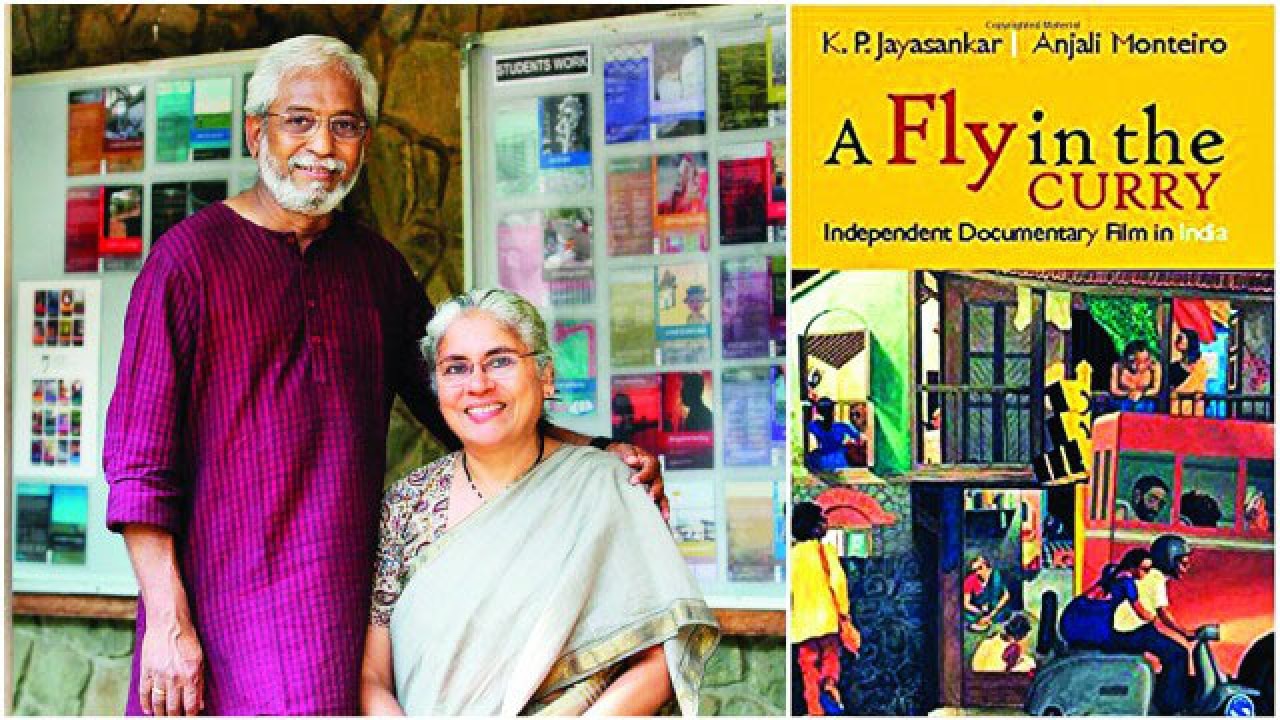

Anjali Monteiro (AM): This was a book we carried in our heads for a long time. It has always been difficult to find material on documentary filmmaking. As documentary filmmakers, who teach documentary as a subject, it has always been a struggle to find literature on this genre, particularly after the 70s when such a rich body of work was created. True, there are a few dissertations and papers which explore certain facets, but there was nothing comprehensive available.

KP Jayasankar (KPJ): There is a particularly large body of a very vibrant work in the field of documentary and there has been very little effort from mainstream media — media historians and critiques have not focused on this rather rich genre of work, as much as, say, feature films. I see the book as a baby step to foregrounding the history of documentaries and their contribution in bringing to the fore the various contestations, questioning the normal and the definitions of what is development, what is culture as also documenting journeys of various social movements.

AM: Despite the point you make, one can't deny the role Films Division played through the 40s, 50s, 60s and even until the early 70s in shaping the face of the non-fiction narrative. Of course, a lot of the Films Division work tended to be preachy, boring and statist but there were works by Mani Kaul, Sukhdev and others which stand out. One can't use one brushstroke for this complex body of work. In the 70s, we see a definite shift to what we have dealt with in the book, and call political cinema. The works of Anand Patwardhan, Deepa Dhanraj and a whole lot of filmmakers comes to mind. But there again, over a period this began to fall into some kind of a mould for documentary making. This went on till the 90s when one sees a shift from what had become the language of the political documentary with filmmakers like Amar Kanwar and others who experimented a lot: both themed and form. The arrival of the internet and digital technology has opened a whole world of possibilities and a lot of lines are blurring between fiction and non-fiction, documentary and non-documentary. Its also become much cheaper for people tell stories with films.

KPS: Documentary films have always questioned the dominant ways of looking at the world. Right from Anand Patwardhan onwards though, there has been little by way of state-sponsored patronage from television or other distribution avenues. Its relationship with social movements has been a very strong factor that led to its development. Because there is no patronage or state funding, each documentary is a labour of love. Especially, if they try to lend voice to the marginalised voices and narratives. Given that, as a form, the documentary has always had a political edge and has faced opposition because of its contestational stand.

AM: We have been fortunate to have institutional support for our work. We have been lucky to have a fairly liberal editorial space without any controls holding us back or telling us what to do. This has allowed us to work with marginalised stakeholders like women's groups, feminist poets and the transgender community with a fair amount of ease. It also helps that we look at politics a bit differently from other documentary filmmakers. We look at the cultural and performative also as the political. It is a notion that power defines normality as a space and this needs to be questioned. A lot of our work falls into this space and the problematising of the self has always been important to us.

KPJ: We work with really young people. The sheer idealism, energy and motivation they bring means they will step on some toes or the other. Their work is largely political since they bring a rare conviction to what they do, unlike us, who have been in the system for longer. Ultimately, they understand better that the actual aim of documentary is to bring the viewer unmediated images of reality. In the times we live in we know nothing, not even news in unmediated anymore. So the political could be the way you look at things, how you build the narrative and your take on issues. Both of us have been privileged to be associated with works which critique dominant notions of representation. A film made by a group of students which looked at the issue of beef and livelihood had got into trouble because of the questions it raised. It was stopped from being shown at a festival after being accepted as an entry. But on the internet it received more than 60,000 views. Ultimately how one counters censorship and regimes of control is also about negotiation. Like during the Emergency, The Indian Express carried a blank page to protest government censorship or two years ago, to protest the ban on the documentary India's Daughter from being telecast in India, NDTV decided to go off air for an hour resorted to 'silent protest.'

KPJ: Censorship takes many forms. From making Anand Patwardhan scrounge around to get raw to stock to shoot where a deliberate attempt was made to stop him from making the film, to refusing it a censor certificate, to ensuring it does not find slots to screen and finally attacking it as a and when it does. I agree there is a lot of control and censorship, but the internet has ensured there is enough, at least till now, for all kinds of work. So one side there is a vertical integration, where those in power or their crony corporates are control every media industry and then there is a large body of very vibrant work which is being created and put out there regardless.

AM: Also there is also an attempt at using such extra-constitutional censorship as means of ten seconds of fame. This is faced by documentary filmmakers, artists and also feature filmmakers. A large part of the opposition to something that doesn't fit in with the moral code of a few, falls under this. It is growing both in frequency and impunity. And this is not only the right wing outfits but even others have not done too much to stop or even criticise such vigilante groups. So we live in a very censorious time and society where unfortunately even the public perception is that it is right to censor or stop something that you disagree with and use means that are beyond the Constitution...

AM: I don't think the media, at least not the mainstream which is largely centrist, has tried to further a left agenda to the exclusion of the right. In any case there are multiple points of view on every single issue. I think media debate is often impoverished by the reduction of everything into a binary. Also one can't homogenise either the left or the right since within each of these folds there are several schools of thought. The point is for people to listen fearlessly. We are now unwilling to listen fearlessly and fear points of view that differ from our own. It is very important to listen without trolling, without attacking, without using all kinds of unethical ways to silence by the state or non-state players.

KPJ: Invariably now everything is linked to Indian culture. As if Indian culture which has been around for centuries if not millenia, can be threatened by a book, a play, a poem or a documentary.

AM: And the vigilante groups know very well that artistes, writers or painters are easy-to-pick, soft targets.

AM: One certainly hopes there is marked difference between the jury and the state. And of course we were not chosen because our work supports/endorses the state narrative on anything. Much of it, is in fact, to the contrary. We know in the past, many documentary filmmakers too have returned awards to protest what was happening at FTII. We see it strategically. If this award helps take the book to more readers and gives it more mileage, then it is good in the long run for documentary. I can't say for sure if there is an element of compromise involved. Maybe if we were really revolutionary, we would have refused to accept the award.

KPJ: I fully get the ambiguity in us accepting this award but remember one can't simply write off all government machinery as the state. We need to also get our foot in the door. If this is what it is going to take to get an inch more of space for dissent, why not?

AM: And where can you draw the line as all dots are connected? Are we going to stop using cameras made by big corporate giants to make our films then? So there is no entirely politically correct position to be in. I think what's important is to strategise and think how best one can give space to unheard voices and opinions

KPJ: But we are not against the critique of our accepting the award and respect it as valid just like we took a negotiated stand of accepting it.