Meghna Gulzar's unusual spy drama Raazi being toasted for crossing the Rs 100 crore mark (and counting) on the 25-year-old shoulders of its more-than-able star Alia Bhatt, also stands out for its nuanced humane portrayal of Pakistanis as a people. Gulzar's adaptation of Calling Sehmat by Harinder Sikka has an Indian female protagonist marry a Pakistani army officer for gathering intelligence. Her spying helps avert a major naval strike being planned by the Pakistani defence establishment in the 1971 Indo-Pak War.

In an era when thumping 56-inch jingoistic chests is in, the filmmaker chooses her words (no surprise there, given her wordsmithery pedigree) carefully while speaking of the genre-defining Raazi's success. “The narrative itself was so powerful. Even a slight jingoistic tinge would take it overboard and ruin it. I was very clear that making a film about India's interests shouldn't necessarily involve Pakistan-bashing and I'm glad the audiences have accepted this breaking of the stereotypical way Pakistanis are portrayed,” she said. “How can we forget that the average Pakistani is human just like Indians. Why would we need to show them as bad to show India as good? The film just makes its point without any loud sloganeering since we weren't setting out to play to the gallery or raise decibel levels just to aggressively push the film's commercial graph. That is just not my style.”

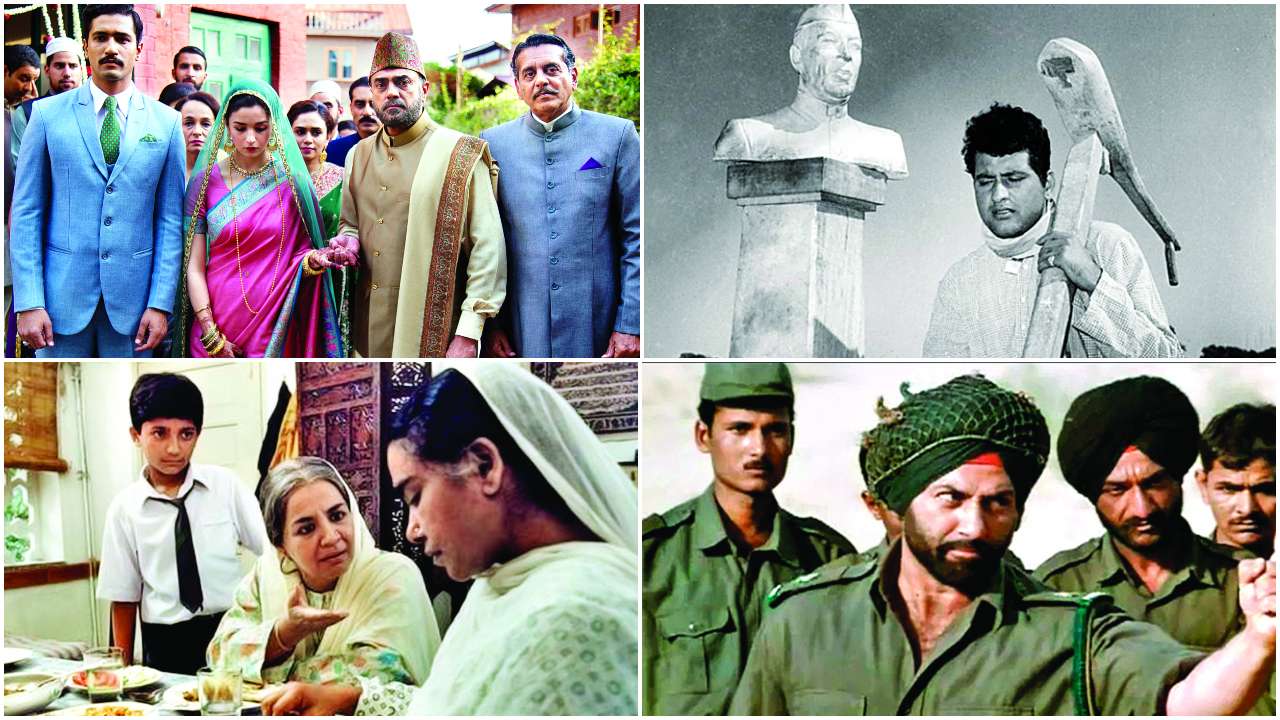

But can Raazi reverse the trend of high octane (fire-hydrant plucking) Pakistan-bashing that helped mint hits like Border (1997), Sarfarosh (1999), Gadar:Ek Prem Katha (2001) , Ma Tujhe Salaam, LoC Kargil (2003) at the box office and an entire assembly line of films which tried to milk this formula? “I don't think it will,” insists Dr Anjali Monteiro School from School of Media and Cultural Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences. The internationally acclaimed documentary filmmaker says, “The immense gains at the box office for these films indicate a huge appetite among audiences. I don't see that changing soon. The political climate also likes to keep furthering only this kind of discourse between the two nations – a militaristic one where we are forever breathing down each others' necks. The film industry seems to be taking its cue from there.”

Others like film and cultural historian Meghna Kashyap echo Monteiro. “When a Rustom beats an Aligarh to a national award, a message is being sent. And apart from rarely rare exceptions, Bollywood is not exactly known for a hard spine. Given the way, such fare is commercially lapped up where is the incentive to explore an alternative narrative? That would mean real research and legwork,” she says citing two examples to underline her point. “Look at Dutta's Refugee or Khan's Kabul Express which didn't make everyone across the border into diabolical demons. But see their later work and the contrast is too stark to ignore,” she says and adds, “Whether 1999's Kargil conflict, 2001's attack on the Indian Parliament, 2008's 26/11 Mumbai terror attack - each has been marked by a strong anti-Pakistan mood which the film industry has milked with films made around these themes.”

So much so that even then Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf once personally pleaded with Bollywood's then reigning star Aishwarya Rai in 2004 “not to act in films that projected Pakistan in a bad light,” during a live satellite address at the India Today Conclave. “I'd like to request a leading star like Aishwarya Rai not to act in such films because they're most unrealistic,” Musharraf had said unmindful of the audience's guffaws.

Recent films have even stopped attempting to build plots around real wars and conflicts and largely take the easy way out with spy dramas (Agent Vinod, Ek Thha Tiger , D-Day, Azaan) higher on production value than content, points out Kashyap. “Though these have had mixed fortunes at the box office, it is a theme that Bollywood doesn't seem to tire off.”

And when Bollywood is not making sworn enemies of them it makes Pakistanis into caricatures in comedies. Like Tere Bin Laden, Welcome to Karachi, Filmistan or Total Siyappa. “Many of these come across as delightful films by themselves but seem to try too hard to keep busy with the passive-aggressive bickering often deliberately side-stepping the elephant in the room, the real Indo-Pak bad-blood,” observes Kashyap.

But this kind of ginger side-stepping has a history which goes back to the run-up to Partition in 1947 and the carving out of a Pakistan from an undivided India. Acute discomfort, with what was seen as a historical embarrassment, meant that this was completely blocked out by filmmakers says Nirmal Kumar, co-author of Filming The Line of Control. “Even any oblique references to Pakistan were astutely avoided. The largely Punjabi filmmakers felt very bitter about the how their land was carved out to draw the Radcliffe Line often affecting their immediate or extended families, memories of which were still raw and painful.”

It wasn't until 1967 classic Upkar that a very oblique reference to Pakistan was made, yet Manoj Kumar shied of naming it in the protagonist's (suggestively called Bharat) moral high ground as he painfully confronts his younger brother who asks for the ancestral farmland to be divided. “Though Chetan Anand made both Haqeeqat (based on the Sino-India war of 1962) and Hindustan Ki Kasam (based on the Indo-Pak war of 1971), the Pakistanis were not shown as brutal and insensitive like the Chinese. “While the Chinese were seen as cold and bereft of emotions, Pakistan was still seen as an estranged brother we were emotionally invested in,” says Kumar.

The 1965 and 1971 wars with Pakistan had begun to stir passions within the country and the far political right began to muddy waters pointing fingers at the local Muslims. “This conflation of the Muslims within India with the 'enemy state Pakistan' is very cleverly and shrewdly manipulated from then on to this day to create the 'other.' It is like the dispensations in power know they have to create two scapegoats – one within (the Muslim community), one without (Pakistan)– to blame for all their own failures as a government,” says Monteiro.

MS Sathyu's Garm Hawa (1973) based on the plight of a Muslim family caught in the crosswinds of Partition was released in this climate. “This film based on Ismat Chughtai's was far removed from the militaristic narrative of two hostile neighbours. It showed the deep connect people on both sides had with each other and established how their existential worries often mirrored one another,” says Montiero. According to her increasing tensions in Punjab and Kashmir where Pakistan was seen as actively fomenting trouble did not help and the animosity only kept rising. “Later generation filmmakers hadn't experienced Partition and were only happy to further the establishment's view,” she points out.

She brushes off any similarity drawn between the Hollywood made all its villains Russians during the Cold War. “The Russians are far too removed from the US both geographically and socio-culturally. This is very different from India and Pakistan where food, culture, music and even rituals are common. In fact, the differences between the South and North of India are far greater than that between North India and Pakistan. So the otherising and vilification takes on distinct visceral edge.”

It would take a heavyweight like late showman Raj Kapoor to buck that trend and release Henna (1991) when the mood in India was strongly anti-Pakistan. “Were it not backed by the RK films banner and its star-spangled cast wonder if it would have been as a big a hit. In fact, its songs are still the rage on the radio even across the border,” points out Kumar.

Parallel and crossover cinema's forays away from the geopolitical have also been able to move the camera lens away from the barbed wires, tanks and guns to hunger, identity and gender helping audiences connect with the resonance they see.

Speaking of his National Award winner Mammo (1994) which came 21 years after Garm Hawa, filmmaker Shyam Benegal modestly passed the credit on to Khalid Mohammed who had based the story on his own grand aunt. “When I read it I was very moved at how it brought home the real pain of Partition without getting to the blood and gore. That was really special about the film. It humanised its characters in a way that everyone, Indian, Pakistani or otherwise could identify with,” says the auteur who adds, “That is perhaps the reason why people still react so emotionally to the film so many years later and come up to Khalid, Farida Jalal or me and speak of the connect they felt with this character who has to face-off with a nation-state.”

Five years later Pamela Rook's Train To Pakistan (based on Khushwant Singh's namesake novel) and Deepa Mehta's 1947: Earth (based on Bapsi Sidhwa's Ice Candy Man) would do the same. Often cited as films that brought out the ugliness of hatred and bigotry we all carry within, Kashyap says she ranks both these a close second to Govind Nihalani's telefilm, Tamas for “the way these films portray polarisation and the dehumanisation of people who in turn carry this forward.”

Which brings us back to why more filmmakers do not make films of this genre. Filmmaker Mukul Abhyankar (whose Missing released recently) should know. After all, he was invited by Musharraf government to train a pool of Pakistani talent to create their own daily soaps. “Commercially a film which shows India and Pakistan in a stand-off will always do well. And Bollywood more than anyone else believes nothing succeeds like success.”

He only admits to being perplexed that the Pakistan government decided to ban Raazi. “Though the film, it is the Indians who are villains masterminding a devious sinister plot and the Pakistanis simply seem to be following their call to duty. In the process, Sehmat ends up killing the family's trusted servant, her brother-in-law and her husband dies in a blast. In fact, when he finds out, he tearfully wants to know if there was ever anything between them. I can understand if they ban Gadar but they should have been 'raazi' for this one!”

Pakistanis vilify India too but it doesn't get as pronouncedly noticed given the size and reach of Lollywood which can hardly match Bollywood in budget and scale.

The PTV series Angar Wadi and Laag (both directed by Khalid Rauf) showed how the excesses of the Indian army pushed people to join militancy. Rauf would go on to make a movie called Laaj with a similar theme. Both the film and these tv series have done very well and still considered iconic by the entertainment industry. An entire generation grew up thinking of Indians, especially Hindus as hostile because of the stereotypes perpetuated in Rauf's work.

Pakistan Military has a media wing called Inter Services Public Relations, not only extra constitutionally censors media content but tried to ensure that all content being put out propagates a pro-army, anti-India narrative. It also provides funds to filmmakers who make content pronouncedly toeing their line.

When Ali Kapadia tried to make a film trying to delve into the reality behind the Indo-Pak relationship his film was stopped. An angry Kapadia says: “ISPR studies scripts in fine detail, does background checks on filmmakers and even lands up on film sets during shoot, to make sure everything appears the way they want. Not having them on board from the beginning means a film can be shut down whenever they want.”