Grief is the emotion that defines the last five weeks for some of us. Watching the US Presidential election results threw thousands into a depression— across the board because of what it said about how Americans really felt about issues that were thought to be history, but for many of us, because Hillary Clinton came so very close to shattering the last glass ceiling in her country’s political system. This week, many of us felt an unanticipated sense of loss when J Jayalalithaa’s death was officially announced. Whether we agreed with her politically (I mostly did not) and whether we had ever voted for her (I had only done so this year), a great sadness was pervasive. Nothing changes that reality.

Supporters grieve Jayalalithaa's demise. (AFP)

“Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?”

Gerard Manley Hopkins asks a young child in a poem I read in Class 10 and have carried in my heart ever since. Why did we react to these two events with such sadness? Why did I?

I belong to a generation that could have never predicted the possibility that an African-American could become the American President. It happened. Twice. When Hillary Clinton won the Democratic nomination in July, we gave ourselves permission to hope that girls in the US too would be able to aspire to this office. Clinton’s feminism falls short by the yardsticks now held up, especially by younger women, but now the once-impossible was close enough to touch. Never mind that the road to Election Day was paved with the most misogynistic baiting— not just by the other candidate but by the media as well. Clinton held her own, with tenacity, grace and focus, and still she lost. That you could give your whole adult life to public service, that you could work so hard, that you could bear with so much, that you could come so very close and still not be considered good enough for a job that went to someone with a negligible fraction of what you brought to the table— that said that women were simply not entitled to ambition or reward. We were disappointed that Clinton did not win, but what we mourned most of all was that betrayal. It was not that merit, focus and effort were not enough. The message was clear— women were not enough. Not good enough. Not smart enough. Not anything enough to make it to the top.

Jayalalithaa’s story is almost the opposite. In a society where all indicators suggest that women cannot succeed, her sustained ascendancy requires us to recast our assumptions. Someone commented that gender was irrelevant to her story. Gender was completely relevant to her story—her objectification in cinema, her vilification in politics—but her success lay in making them seem irrelevant. Notwithstanding her welfare measures, Jayalalithaa’s politics were gender-blind. Jayalalithaa also belied any essentialist argument for women in power— that they will bring nurture and gender sensitivity to their work. Like any other politician, she has left behind a conventional, mixed track record on the “women’s empowerment” score. Many of us are sad to think of the journey that brought her to this pre-eminence— the price she paid at every turn breaks our heart because we know that is the price every woman politician pays in every patriarchal society. Jayalalithaa was an easy target because she came from cinema to politics— even criticism about her policies was tinged with disapproval of her relationships and her appearance. Even when we disagreed with her on most counts, her presence affirmed that women could force the world to take them seriously. When the mutterers and mockers got done, they would find she was still one of the most powerful people in the country.

(PTI)

“Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow’s springs are the same…

It is Margaret you mourn for.”

Hopkins holds a mirror up to our grief, saying that we mourn for who we once were and can never be again, and we mourn also for what we could never become. In Clinton’s loss and Jayalalithaa’s death, we have seen mirrored our own journeys— coming up against speed-bumps, obstacles, landmines and glass ceilings everywhere. Our grief tells us how every barb they faced mirrored one in our own experience.

Hillary Clinton giving her concession speech the day after the election. (Reuters)

Clinton and Jayalalithaa had much in common— sharp minds, great work ethic, tremendous ambitious, tenacity, resilience, tumultuous personal lives that kept getting dragged into public discourse and both faced unbelievable sexism and body-shaming. We hurt at their loss because it brings back the wounds of every loss and every jibe we ever faced. The accidental-done-on-purpose forgetting to include us in discussions. The so-called compliment that draws attention to our bodies and away from our professional presence. The friendly advice out of fake concern about our health that undermines our confidence. The unspoken quid pro quos—to forget the things people say and do (the everyday sexism) or to overlook the thing they fail to do (like giving you credit)—in order to keep an oppressive peace. The clinging on to the high ground because it’s the right thing to do, though your fingers hurt and your eyes smart. The hurtful jokes that never sound funny. The dismissal of our ideas that precedes their being co-opted as someone else’s original thought. The creation of standards for our success that do not apply to anyone else— must be personable, must be brilliant, must work hard, must not be ambitious, must not want credit, must not upset the apple-cart, must know her place. Clinton’s election loss and Jayalalithaa’s final departure allow us to cry and rant for all the times in our lives that we have kept quiet.

It is Margaret we mourn for.

The child in the Hopkins poem has no way to change or reverse either autumn or growing older. But, in our hands, lies the ability to make women’s political activism and participation a less hazardous choice. Since it is also the season of year-gone-by reviews and resolutions, here are some thoughts for things we can work on in 2017 so that we do not feel this grief again.

In 2017, we expect five Indian states to elect new legislators— Goa, Punjab, Manipur, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. This means we need to get started right away on asking the right questions, lobbying for some bare minimum commitments, holding parties accountable to them and monitoring the election closely. This is civil society’s work— and we are all part of civil society to the extent we choose to be pro-active citizens.

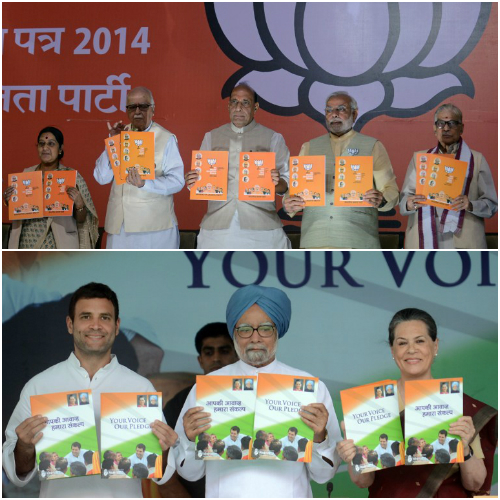

Political parties go through the ritual of preparing manifestos. A couple of decades ago, because you could not circulate them very widely and because a healthy scepticism then animated our democracy, we saw these as rituals and manifestos as largely interchangeable. We ignored manifestos routinely. Now we analyse them when they are published but forget to hold winning coalitions responsible for keeping their word. Anyway, since we do seem to think manifestos matter, ensuring gender inclusivity in the issues addressed and gender sensitivity in the language and approach would be a place to begin. Who drafts manifestos and who finalises them? These are the people we need to sensitise.

The second challenge in an election season is ensuring that there is gender parity in the allocation of election tickets. How many women are being nominated and who are the women being nominated? Apart from petitions and demands, one useful intervention in each state would be to create directories of women that belie the usual excuse: “Where can we find competent women?” Forget pointing out that competence is not a requirement for male nominees; it would be more constructive to simply provide lists of Panchayat and Zilla Parishad women as well as women social workers from villages and district towns. Is this something we can do in each state?

Black money is not the only campaign finance issue that needs to be addressed. Access to campaign support is gendered and parties tend to neglect women candidates in their apportionment. For structural reasons, it is much harder for women to raise funds to campaign. Recognising this, a non-profit in the US, EMILY’s List, identifies women candidates who espouse a set of core political values and helps them raise funds. (‘EMILY’ stands for ‘Early Money is Like Yeast.’) India does not have a comparable culture of political giving so an Indian EMILY’s List is two steps away— creating a culture of individual support to political parties and creating a demand for good women candidates such that people will pay to support them. A more immediate goal would be to engender the campaign finance reform conversation, itself only a faint thread in political discourse.

Related to money is the on-ground political support for female candidates. Often in my constituency, a major party does nominate a woman. But unless we really research the candidates, we continue to know little about the person. Too many of us in the voter queues read the Election Commission poster and make a random choice on the spur of the moment. Nomination is the beginning of the journey; female candidates also need a share of political workers who can canvass votes, public and media relations support to raise their profile and ground-level support by more prominent party leaders. This is also a good way to judge a party’s commitment to gender equality.

Even easier, because outrage is how we talk politics now, is to call out misogynistic speech and signal that it is now unacceptable to us. The election campaigns to come will be bitterly fought and because women leaders will figure prominently, the vitriol will probably be patronising and sexist. The simplest—laziest—thing we can do is to monitor hate speech and communicate our disapproval in a variety of ways— social media posts and reactions to petitions. Can we commit to cleaner, more inclusive and less ad hominem campaigns?

In May last year, before the Tamil Nadu Assembly elections, Prajnya put together a Gender Equality Election Checklist which may be applied to any election context.

Elections place a spotlight on women’s political exclusion, but really, the time to change that is in the years between elections. Off-season, it becomes clearer where the choke points are, and what can be done to remove them. Off-season, it should be easier to approach one’s representatives and local activists and initiate first conversations about local gender concerns. The years between elections are particularly suited to three sets of important interventions.

In the years since gender quotas were introduced into local government, a great deal has been invested in training women Panchayat leaders. However, once trained and armed with experience, these women find they have nowhere to go. Doors open to a minuscule percentage of them at the next level. For the women who cross this threshold, the policy issues are relatively different. The election off-season is a great time for creating training processes and access to policy education for women who have been in Panchayats and are either seeking office at other levels or have been elected at other levels.

It is also a good time for civil society to build two kinds of relationships. The first is a consultative equation with legislators that can inform Parliamentary debate on specific issues. Ideally, both sides should seek this out, but typically, civil society does so halfheartedly and the platforms acquire a ceremonial rather than substantive cast. The rare MP or MLA that really wants to sit down and learn and talk through issues is the one that must be feted in the ways that matter— not bouquets and panegyric but through letting people know that these are serious people. Let us reward people for their advocacy of gender issues and their willingness to be identified with inclusive ideals.

The second is to create, host and facilitate cross-party alliances on key gender issues. Some things are truly above politics— equality should be one of them. Inner-party politics in India, especially at the state level, divests members of autonomy when it comes to any policy or issue engagement. Party members seek permission for the smallest thing and a siege mentality coats every casual conversation on a social issue with the tinge of possible betrayal. This paranoia may serve parties in some obscure way but it serves us not at all. Can we start to tinker with this thinking in small ways and to build the alliances that will foster true, substantive debate?

Where will the women emerge from in nomination season if we have not made them visible in the off-season? I address both civil society and media here. The rosters and directories I spoke of earlier cannot be assembled overnight. The networking opportunities take time to create. Civil society and media are uniquely positioned to sift through false claims and to create openings for sustained, deep social engagement for women who seek a political career. Making women in public life visible is also a way of protecting them from violence and of supporting Women Human Rights Defenders. Moreover, despite how we think of politicians, many women political activists lack simple media and communication skills. How to organise and deliver a speech, how to canvass, the art of writing a pamphlet or a press release, how to use the internet— these are skills anyone can learn and these are skills we can teach each other as a form of support. This is the time to invest in building that kind of capacity.

The death of Jayalalithaa this week and Hillary Clinton’s electoral loss a few weeks ago should move us towards action. The sense of purpose we universally admire in them must now inform our choices in 2017. The glass ceiling does not need to shatter; it can systematically be lifted off by our collective resolve and effort. I will make that effort; will you?

Swarna Rajagopalan is a political scientist by training and the founder of Prajnya, whose work is largely focused on gender equality.