I am an admirer of the Roman Catholic Church because of its historical importance. I would not for a moment overlook its many moral crimes and its worldly arrogance. On the positive side, the Church had been a beacon of learning and a civilising influence through the nebulous Dark Ages from the fall and end of Rome in 455 CE (Common Era) to the emergence of Charlemagne at the beginning of the eighth century CE, soon after the Battle of Poitiers in 732 CE when the Franks defeated the Arab armies.

It is this turn in the fortune of a battle that kept Europe Christian. It could very well have been an Islamic Europe had the Arabs won. Of course, this is a debatable point. King Ferdinand ll of Aragon and Queen Isabelle l of Castile re-established Christian dominance in political terms despite Islam having flourished in southern Spain for about 800 years. It was again the Roman Catholic Church that provoked or inspired, depending on the point of view, to set out on the Crusades in 1095 to recapture Jerusalem which was under the control of the Arabs. In the complicated episode that was Crusades, which lasted for a century and more, the Europeans were able to absorb the material and cultural achievements of Islamic Arabs. The main purpose of the Crusades was to defend the Eastern Roman Empire. But it failed in this main objective. In a space of three hundred years, Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453 CE and it became an Islamic outpost in Europe. It was only in the 19th and 20th centuries that a nationalistic Europe retrieved many of the territories

But in its many clever contrivances to survive and dominate through changing times, the Roman Catholic Church had invented this system of canonisation in a formal and almost a legalistic form. In other religions too, there is the natural reverence for the people of high piety. But the Roman Catholic Church has institutionalised the process and given it a bureaucratic visage.

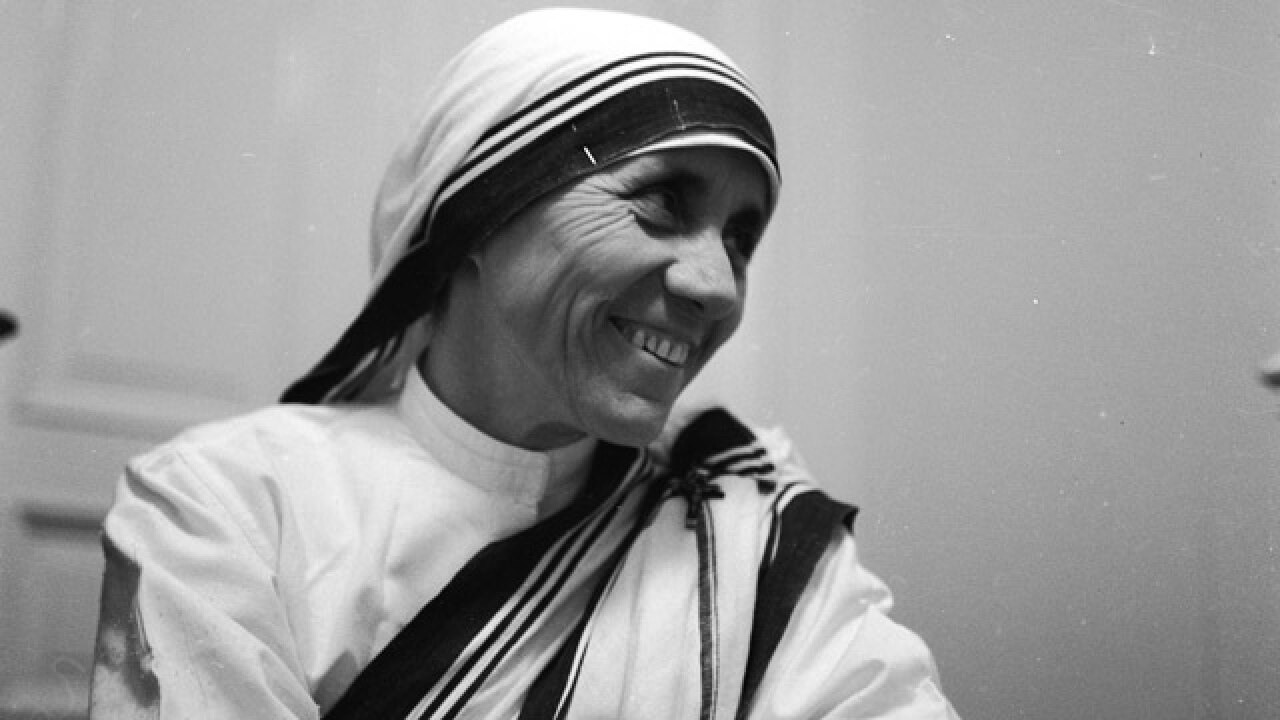

Mother Teresa was a simple and unquestioning believer of the Roman Catholic Church. Whatever might have been her agonies of faith in her moments of inner solitude and utter loneliness, she was a soldier—proud and humble—of the Church. She must have venerated the many saints of the Church with unfailing devotion.

Two uncomfortable questions arise in the context of her canonisation. First, people in Kolkata and in India who already revere her like a saint will not be too impressed by her canonisation. For them she is already a saint and they do not need the imprimatur of the Church. It seems that it is the Church that stands to gain by the canonisation of Mother Teresa. The Church gains a sense of legitimacy which it had been losing over the last few decades, especially with the exposure of child abuse by priests of the church.

The second uncomfortable question is this: The Church has shown undignified haste in moving towards canonisation. Yes. It is now 19 years since she passed away in 1997. It can be said that a span of nearly two decades is good enough time. The stories of miracles, which are matters of faith and to subject them to rational scrutiny is an irrational thing, do not seem to have passed the difficult hurdle race that the Church had created to make it doubly certain that the miracles were not hoaxes. More accurately, that the miracles were not conjured by the Devil—the Devil is a real entity in the Church jurisprudence—and that they emanated from the goodness and holiness of the person to be canonised was an essential phase of the process. There appears to be some laxity in the stringent procedure that the Church had set up for itself. It is the unwillingness to let more time pass and the dust settle as it were on the living memories of the people who had seen Mother Teresa that betrays a sense of anxiety on the part of the Church.

It is the inherent right and privilege of the Church to choose its criteria for making a person saint. Perhaps it would make more sense if Mother Teresa is declared a saint not on account of the putative miracles but because of her service to humanity, of her compassion towards the poor and the sick and the dying, and her own intense and unwavering faith in the Church. It will be argued that canonisation is not a good conduct certificate, that it is not a Nobel Prize for Peace, that it is not an Olympic gold medal. It is rooted in theology and miracles are part of that theology. It will indeed be difficult to argue against this contention whatever the objections of agnostics and sceptics.

While the Church must stand by its own convictions—and its theology is an integral part of its belief system—it must then, to remain credible, show the immense patience before it decides on making any person a saint. The Church has not shown its traditional forbearance of late and it seems to be in a hurry to declare some of its devout followers as saints.

Many people in India, and not just Christians, are happy that a person who has settled in the country and who has served Indians, has been made a saint. There is the view that the Church is looking for saints outside the Western world because there is the strong belief that the Roman Catholic Church is representative of the Western world, especially Europe and therefore of Western civilisation. The impression is that the Church is trying to get rid of its image as a Western institution.

There are those anti-Church, and anti-Christian, Hindu right-wingers in India who have been very hostile to Mother Teresa and her missionary work. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) Sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat had alleged that Mother Teresa’s work was motivated by the proselytization impulse. The secularists, and not so much the Christians, took umbrage at what they perceived to be the anti-minority tirade of the RSS. But Mother Teresa did not ever say that her work was humanitarian. She knew that she was working for Jesus and that she perceived Jesus in the suffering humanity that she was striving to serve. The RSS misses the point that Mother Teresa was willing to work for God, yes, her God, and that it did not involve any hatred towards any other religion. The RSS is no believer in God, and it has its own god, the nation. Of course, the RSS too adopts the fake rhetoric of the secularists— humanitarianism.

The other line of attack against Mother Teresa is that her religiosity was so blind and narrow-minded that she refused to use the benefits of modern medicine to alleviate the suffering of the people she tended. There is much strength in this criticism. But Mother Teresa’s position is morally consistent. If she believed in the compassion of God, she cannot yield to the temptations of the miraculous cures offered by medicine. There is something heroic in her defiance of medicine, which is indeed the sign of total faith. It is indeed a difficult issue and Mother Teresa seems to have chosen.

I think the way to rebut the RSS is not to deny that Mother Teresa believed in missionary work, but to say that she was honest and sincere and that she did not hide behind humanitarianism as the RSS hides behind terms like nationalism and humanitarianism. In these days, it needs immense courage to believe in God, and more importantly in the Church. Mother Teresa did.