What is the last news that you have heard of Pakistani cricket? That their national team lost disgracefully to the rising Bangladesh? Or that they failed to impress in the World Cup? Or that they failed yet again to beat India in the World Cup? Or that once more Pakistani cricketers are barred from playing in the IPL? Have you heard, by any chance, the news that bilateral international cricket is soon returning to Pakistan or read that warm and respectful tribute to Misbah ul Haq? My guess is a majority of the readers would say no to the last two questions and yes to the rest.

And that is not particularly surprising. The Indians’ attitude to Pakistani cricket these days is governed by the contempt reserved for a hopeless loser. The trouble is that it hides our own insecurities. Mocking Pakistani cricket or cricketers does not make them any worse. In reality, it shows up the Indian cricket fan as a shallow and insecure animal and the Indian public on the whole as a petty tribe. There is nothing sporting about it all.

In the Eighties, the Indian cricket fan would be haunted by the demon of Pakistani cricket. The prospect of losing to Pakistan had assumed the proportion of a national calamity. The tortured history of the two countries, including a painful separation at birth and three subsequent wars, certainly contributed to the magnification of bilateral cricket matches into Orwellian wars minus the shooting. Even if the two met in a third country, muscles would be flexed in the media reports and fans would go into a frenzy, holding their lives in suspension during the match, waiting to celebrate a victory as a deliverance or to mourn a loss as a national calamity.

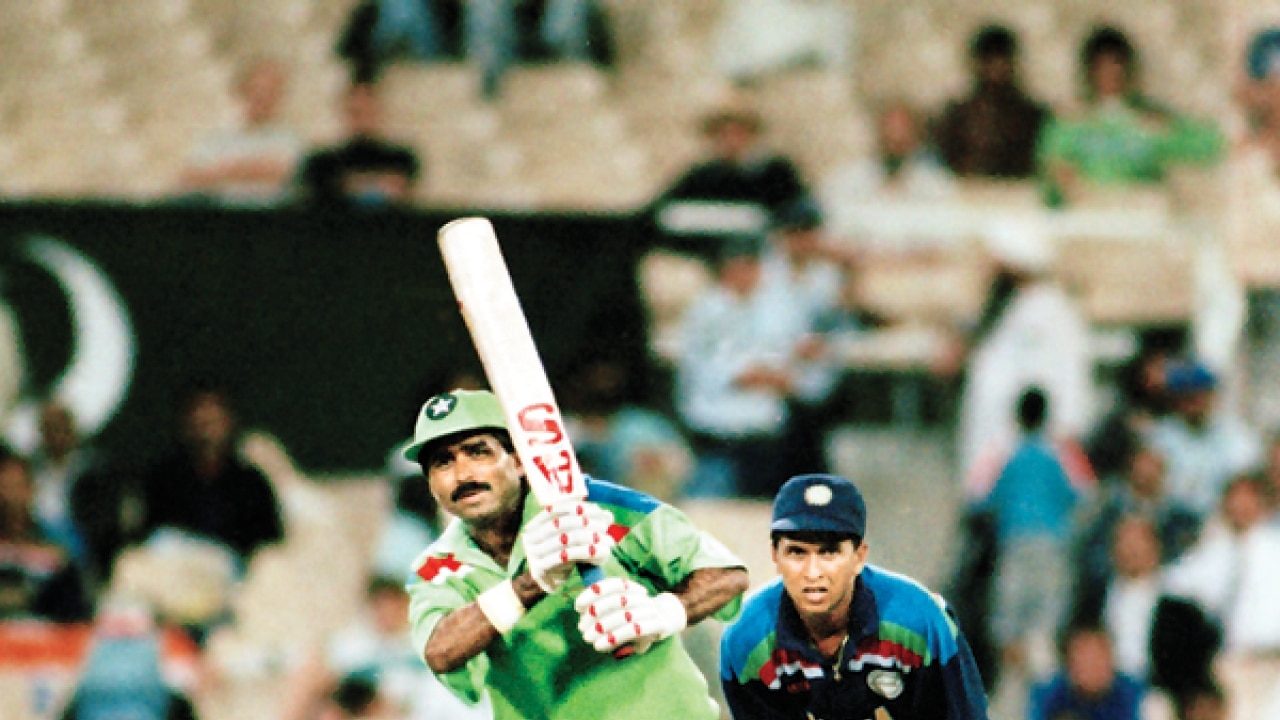

All discussions about India-Pakistan cricket among Indian fans since 1986 would invariably refer to that last ball six by Javed Miandad. That single delivery has contributed sufficient notoriety to the otherwise modest international career of the bowler, Chetan Sharma. On the other hand, Javed Miandad grew into this singularly haunting nightmare for the Indian cricket fan. They could be reduced to silence with a mere mention of that blow, as if it was the unkindest cut ever inflicted on Indian cricket. The collective dread subsequently spiralled into dystopic proportions in 1992 when Pakistan brought the World Cup home for the first time. Humiliation could not be harder for the Indian fan.

Then there descended the deliverance day, that day in 1996 when the Indian cricket fan was restored the confidence to face the world. Amir Sohail hit Venkatesh Prasad for a four and pointed his index finger towards the boundary, as though ordering Prasad to fetch the ball. It is not clear if Sohail momentarily lost his focus after that dismissive gesture or Prasad produced a magic for the next ball. Sohail went for a wild heave and missed, only to have his stumps knocked down. By then Miandad had grown too old to revive his 1986 magic. His desperation — as he ran out of partners — made for delightful television. Pakistani batsmen subsequently failed to chase the Indian total and India immediately erupted in mass hysteria. The demon was finally confronted and put to rest.

By 2015, it had been nearly 20 years since Pakistan won a World Cup match against India. Meanwhile, their iconic players had retired and their replacements could not quite rise up to the challenge of consistent excellence.

In addition, political instability prevented the organisation of international cricket in Pakistan for quite some time. Pakistani players cannot participate in IPL, the most rewarding cricket league in the world. A far from perfect infrastructure of domestic cricket, accentuated by these external reverses, has now turned Pakistani cricket into a pale shadow of its past. If it was the demon haunting the Indian cricket fan until the Nineties, it is now the favourite cricket weakling for them to mock.

You remember those meek and naïve classmates — don’t you? Ones you regularly bullied or taunted in school? You — the bully of the class — were either followed or admired. You thought your bullied classmates did not fit in and you were anyway secure in the knowledge that they could not hit back. The irony of course is even those bullied or taunted in the past turn into bullies themselves, at the first available opportunity.

Unfortunately enough, the Indian cricket fan too is a victim of this bully syndrome which inflicts a majority in our society. The very Indian fan who dreaded a match up with Pakistan before 1996 now looks forward to it in the safe knowledge that Pakistan today is a spent force, that it cannot anymore disgrace India on the cricket field. A match with an emasculated Pakistan is nonetheless marketed as a mock war between the two countries. The marketing of an event, where an Indian win is more likely, as a war of sorts is simply an engineered spectacle for popular consumption. Indeed, if the teams were evenly balanced, and a contest between them carried an equal potential of an Indian loss, it would not require such aggressive branding in the first place. Aggressive marketing in this instance is an instrument to offset an anticipated decline in popular interest. The India-Pakistan cricket rivalry myth is reinforced with an overdose of excitement precisely because it has for a while turned into a one-sided affair.

This is precisely why the Indian media is not interested in reporting news with a promise of revival for Pakistani cricket. They have no space to report that Zimbabwe has actually agreed to visit Pakistan in May. It is not suggested that a single trip by lowly Zimbabwe will in itself restore the standard of Pakistan cricket to its former excellence. Yet, for a country struggling on many other fronts, it certainly is welcome news. If the tour manages to pass off without any fresh security concerns, it will hopefully be a baby step forward to an eventual return of international cricket at home. That could in turn strengthen the call for an entry of Pakistani cricketers in IPL. All of this, of course, is still in the realm of future. But the shallow outlook of the Indian cricket fan and limited interests of the media are right here, refusing even to acknowledge their indifference to the greater cause of cricket.

The writer is an aspiring historian who addresses topical issues with a larger perspective