Never was the human body so bent by its own soul,” said the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke about French sculptor Auguste Rodin’s “The Muse”, also called “The Inner Voice”. To him, the bent form signified intense listening “to one’s own depth”. Rodin subsequently freed the figure of arms and drapery, and called it “Meditation”.

Not surprising that Rodin originally intended this image for his “Gates of Hell” panel – surely, that’s the place where the inner voice will become totally inexorable. Then he modified the naked image to stand beside a naked Victor Hugo in the novelist’s monument that he was commissioned to assemble. Predictably, the authorities rejected the “preposterous” idea!

My interest in Rodin began when I read his essay on Shiva Nataraja (1918), a poetic and personal response to the photographs of the dancing god’s bronzes from the Madras Museum (yes, from my own city). I read about the sculptor, looked at photographs of his work and came across some of his striking bronze and marble figures in museums.

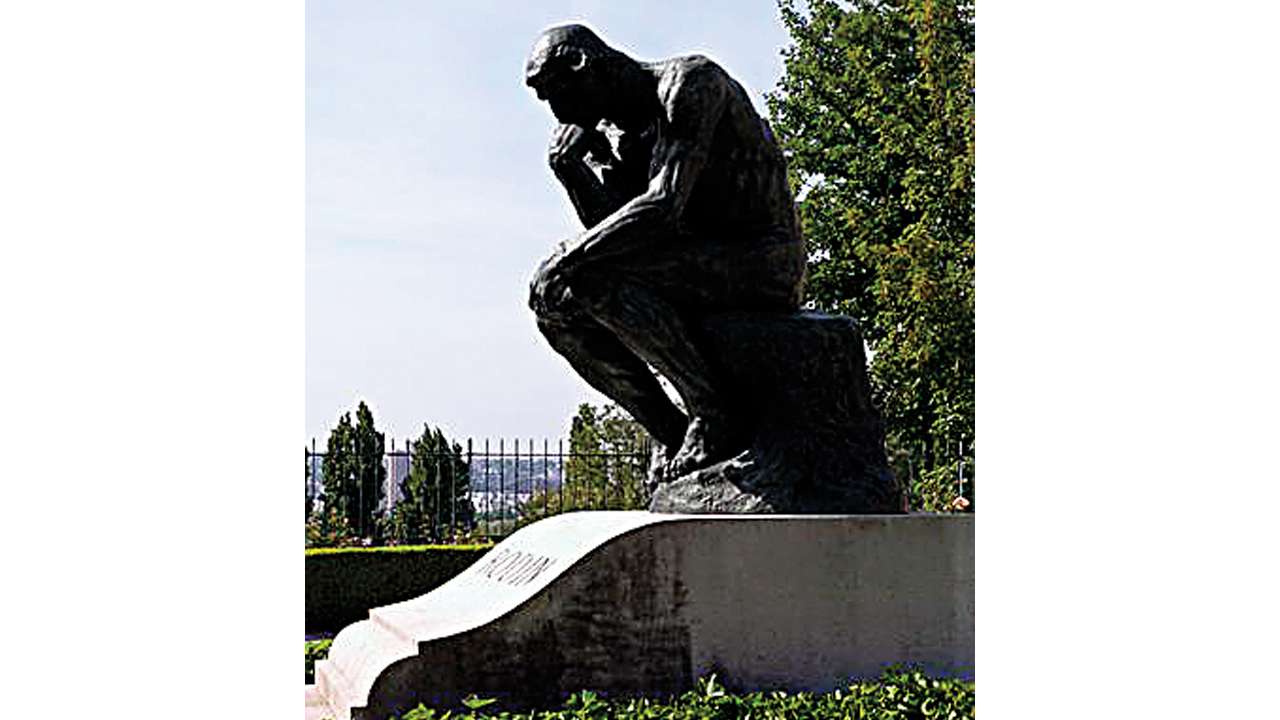

However, such encounters cannot quite prepare you for the impact of a collection of his work. Especially if you come out of a cold underground tunnel in London and run into “The Muse” in a sunlit gallery (Victoria and Albert Museum). What a perfect counterpart it made to Rodin’s most famous work, “The Thinker” which had riveted me earlier at a Rodin exhibition (Art Institute, Chicago)!

Both bronzes show you just how awesome and burdensome the act of thinking can be. You can see contemplation as a struggle for the body as well as the mind, demanding as much physical as mental energy. It is not The Thinker’s face, but his torso that overwhelms you – tense, taut, every vein standing out, every muscle stretched, every nerve on edge. Why, the man with the bent head could be intoning Hamlet’s words, in his own silent soliloquy, “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space...” And the Muse could be adding a caveat, equally silently, “were it not that I have bad dreams.” However, with all the ambiguities in her posture, she could also whisper, “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

It was natural to believe that these two male and female images freeze that crucial moment when human imagination churns deep within. In the crouching thinker, the straining of the torso is surely the struggle of creative expression, as it is in the bent and armless Muse, striving to inspire – and be inspired. Of course, as in most of Rodin’s work, we also see how these male and female images reveal the sculptor’s own tussle to embody his vision in material so stubborn and intractable, that it refuses to be anything but concrete.

How does the sculptor meet his challenge; how does he make stone refract light?

Rodin had seen how this magic was perfected in the bronzes of Shiva Nataraja. He noted “the materiality of the soul that one can imprison in this bronze, captive for several centuries.” He saw the fusion of dance, poetry and sculpture in its “perfect expression of the rhythmic movement of the world”. The dancing Nataraja showed (what he was trying to achieve in his own work) that the sculpted body – in bronze or stone – could capture a still moment among constantly shifting movements. Then, a light was switched on and the rhythms of poetry released.

Rodin had never seen Indian dance live. But since his greatest artistic concerns were about life and light, I was not surprised to learn that he sought them by drawing pictures of karanas or dance movements mentioned in the Natyasastra, the ancient Indian text on dramaturgy.

It is a cliché to say that the West sees art as a mirror of life, plane, convex or concave – flattering, magnifying or distorting. But a reflection none the less. However, standing before Rodin’s “Prodigal Son”, a celebrated structural marvel, I could not help wondering if the sculptor knew that the East believes that art is at best a revelation – at least, it is the resonance of something beyond. Rodin casts the prodigal son, a wastrel returning home to beg his father’s forgiveness, in a posture incredibly imbalanced. However, his teetering body and out flung arms suggest not just human grief, but the possibility of receiving that rare gift: human compassion. Does Rodin’s image mirror how low we can fall? Does it reveal how high we can rise?

The author is a playwright, theatre director, musician and journalist