Rather like Aldous Huxley, Colin Wilson died on the wrong day. In Huxley's case, this was November 22, 1963, when John F Kennedy was shot. Wilson died on the same day as Nelson Mandela, and was thus largely ignored by the media. Yet, there was no guarantee that a better choice of day might have got the world to sit up and take notice. Wilson was 82, and a far cry from the "24-year-old genius" who had burst on the literary scene as England's home-grown existentialist and answer to Jean-Paul Sartre. His wish was to live to be 93, the age at which his hero George Bernard Shaw died. In his first autobiography, Voyage to a Beginning, Wilson said he regarded himself as the most important writer of the 20th century, adding, "I'd be a fool if I didn't know it, and a coward if I didn't say it." Many agreed with him.Many saw him as a crank, author of books on the paranormal and criminology, on serial killers and booze and biographies of mystics and Jack the Ripper. Older readers remembered him as one of the 'Angry Young Men', a group of working class authors who found success around the same time in the mid-50s.

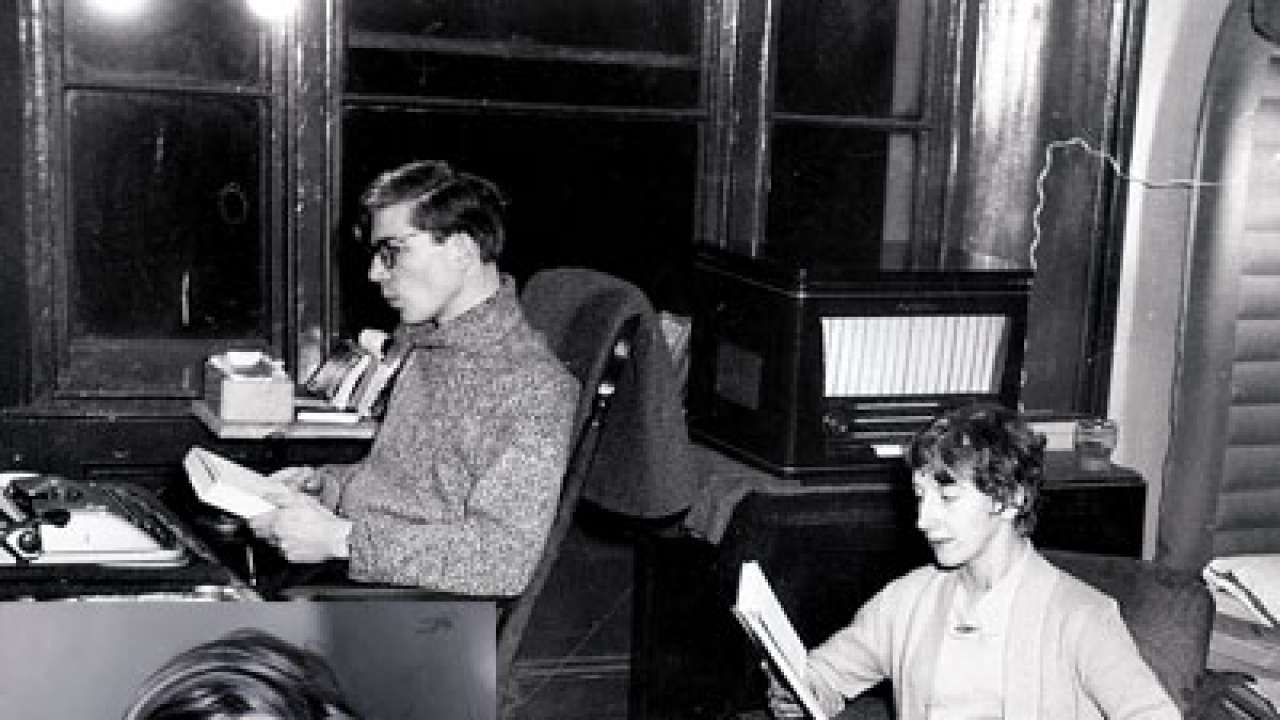

Men like John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, John Braine, Allan Sillitoe, Arnold Wesker: talented writers who were squeezed into a media invention.Wilson was self-taught and by 24 had read more than most might in a couple of lifetimes. He slept in a sleeping bag in Hampstead Heath and wrote by day in the reading room at the British Museum. The Outsider, a journey through alienation, first spoke of a "positive existentialism", a counter to the negative approach of Sartre and Heidegger. Wilson saw the problems raised by the Continental philosophers as genuine, but found their solution, or lack of one, both depressing and unnecessary.I must have been 15 or 16 when I first came across The Outsider and was stunned to know that adults asked the same questions that adolescents did — some of them then went on to look for answers, others let the idea of there being no answer overwhelm them. But this was not so much an introduction to philosophy (although it was a fine introduction to philosophers from Locke and Hume and Descartes to Nietzsche and Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard) as a drive through literary criticism.

Artistic alienation was a broad enough category to include TE Lawrence, Vincent Van Gogh, Vaslav Nijinsky, Ramakrishna Paramhansa, Gurdjieff, TE Hulme, Dostoevsky, Eliot, Kafka and others.It was a fascinating read at that age. We — a classmate, Anil and I — were old enough to understand that pessimism was more stylish, and more likely to impress girls, but young enough to hope for hope. It was some years before we could slot Wilson correctly. He was not the philosopher we had thought he was, but a literary critic with a fascinating theory and a wide range. But all that was in the future. We devoured The Outsider series (six volumes, plus a seventh, which was a summing up: Introduction to the New Existentialism). We accepted or rejected a writer based on what Wilson had to say about him. There was something exhilarating in the message that we could change the world. Or at least become rich and famous just by thinking and writing.The everyday world might be boring and trivial, but the wider world of art and literature had infinite interest. We tend to forget the latter, and get trapped in the former.

If Wilson developed a cult following it was because he confirmed many of our suspicions at an age when "philosophy" and "literature" were still things that other people did.Ultimately, it was the literature that mattered. Wilson's criticism. Eagle and the Earwig, The Craft of the Novel, The Books in My Life, Poetry and Mysticism retain their freshness and originality after all these years. Amazingly, The Outsider cycle was completed when Wilson was just 34. It was too early to become the grey eminence of philosophy (for one, Bertrand Russell was still alive, as was Karl Popper); Wilson chose the alternative, spreading himself over a range of subjects and arriving at the same answers through different routes.He could not shake off the biggest criticism of his oeuvre of more than 100 books: that he wrote the same book 100 times. The actress Mary Ure, wife of John Osborne called The Outsider an anthology of other people's ideas. The reviewers who had called Wilson a genius when The Outsider appeared — like Byron, he awoke one morning and found himself famous — seemed embarrassed by their high praise and tore into his next book.

While that did not guarantee instant anonymity, it gave Wilson the time and space to work without any intrusion. It also might have caused him to take on some commissions just for the money. In an interview following the release of his autobiography, Dreaming to Some Purpose, Wilson was asked if he'd had much influence as a philosopher. His reply is revealing: "Oh no!" he told the interviewer. "None at all. Daphne Du Maurier said to me that everyone who has a great success finds that the next 10 years are very difficult — they have a period when people take no notice of them. And I thought, No, not 10 years, I couldn't bear it! But I've been forgotten for almost 50 years. It's been a bit discouraging… but when I'd done this new autobiography, I looked at it and thought my God, this is a bloody good book! Now they'll see what I'm getting at!"How wonderful it is to keep a vision alive for half a century and to continue to believe in personal genius till the end! For those of us who woke up one morning and found ourselves a friend in Wilson, he is like a favourite uncle. We know his weaknesses, but we don't care. All boyhood heroes are beyond criticism.

The author is currently Editor, Wisden India Almanack