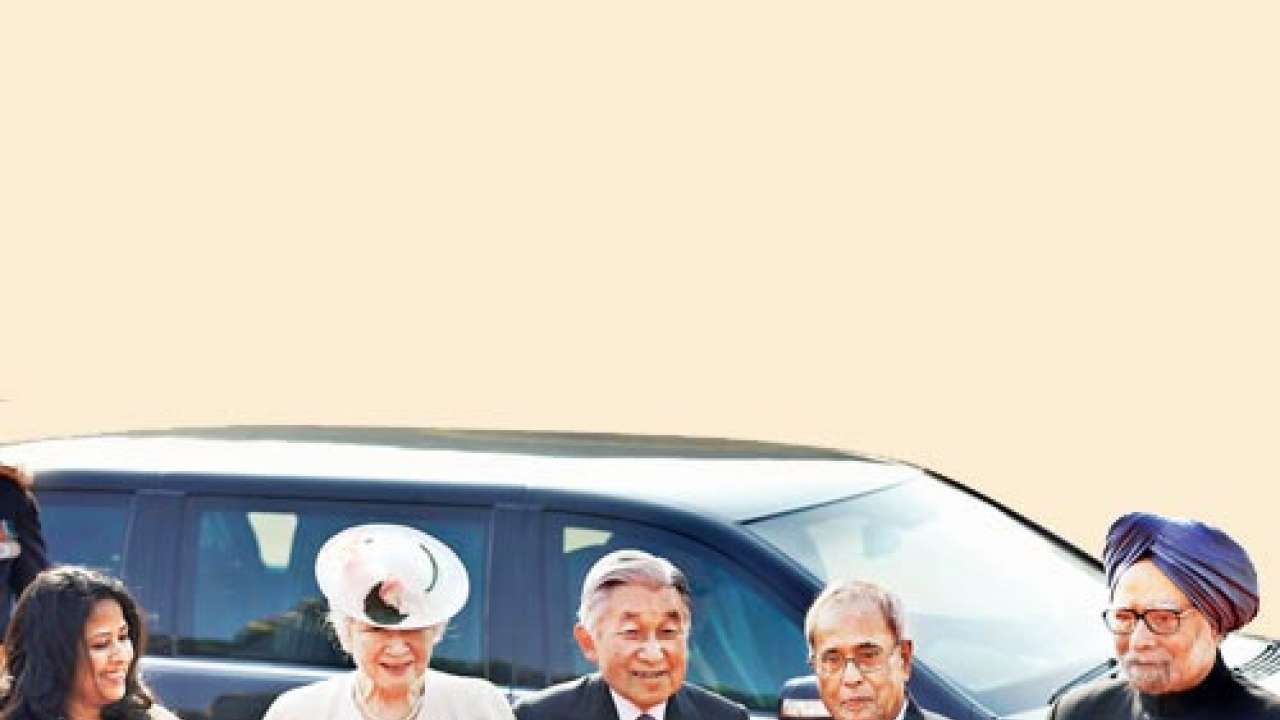

The visit of Akihito, emperor of Japan, and his wife Michiko, to India has been heralded as a major marker of the growing importance of the Indo-Japan relationship. The visit of any head of state is important but the Japanese emperor occupies a peculiar position in his own society. He is no longer a god, but it seems he is still far from being an ordinary Japanese. To begin with the most obvious distinction: the emperor has no last name. He is just Akihito, not that anyone in Japan would use it.

The lack of a last name is the least of the differences that mark the ‘tenno’ or heavenly sovereign, as he is known in Japanese. ‘Tenno’ means more than an emperor; it conveys the divine character of the position. Japanese mythology, enshrined as history, shows that the emperor is a direct descendent, 125th in an unbroken lineage, of the Sun goddess. Archaeologists contest the fictitious genealogies that have built the myth but they cannot excavate the ancient imperial tombs as they are family tombs to provide conclusive proof.

The divine emperor was the core element in modern Japanese nationalism that powered Japan’s drive to build a rich and powerful nation and a vast colonial empire. Under the US occupation, after World War II, many of Japan’s pre-war institutions were changed but the emperor was absolved of any responsibility for the war. He famously renounced his divinity, but the somewhat ambiguously worded statement did not stop others from continuing to rest their claims of Japanese exceptionalism in a if not divine, then an imperial house with an ‘airy existence’. Japanese conservatives claim to act on his behalf but where does he stand on these issues?

Hirohito’s legacy is highly contested as his reign spanned both the pre-war phase of Japanese expansion and the post-war period of ‘miraculous’ growth. Akihito, as crown prince, won hearts and minds by marrying a commoner but, as emperor, he has presided over a nation in doubt.

When he came to the throne in January 1989, the stock market was at a record high and Japan seemed set to fulfil its promise of becoming the next great global power. Within two years the bubble burst and Japan entered a ‘lost decade’. Even as Japan declined economically, China began its remarkable transformation emerging as a global economic and political power. This reversal of fortunes has created deep fissures. The Japanese are divided on how to cope with the social problems of an aging society, rising unemployment, increased immigration and the sceptre of a rising China. Extreme nationalism provides one easy, if false, answer while others seek to rethink many of the assumptions that Japan has been built on and create a more open society.

The conservative right calls for a return to ‘traditional’ values, refuses to give immigrants working in Japan the right to vote, and calls for a strong foreign policy built on US military alliance.

Yasukuni, the Shinto shrine where Japanese soldiers are enshrined, has become a major symbol of this viewpoint. Class A war criminals, condemned at the Tokyo trials, were enshrined in 1978. Conservative politicians regularly visit Yasukuni but what has been ignored is that Hirohito never visited the shrine after 1975 because he objected to praying for the war criminals.

Akihito has continued to stay away. It is a clear statement that, to my mind, stresses the democratic character of the monarchy. During Akihito’s enthronement ceremony, when the debates were focused on ancient rites and their present significance, he again underlined his commitment to democracy by saying that he would obey the Constitution. Even more remarkably, in 2001, on his 68th birthday, when Japan was looking to co-host the World Cup finals with South Korea, Akihito dropped a metaphorical bombshell. He said that he felt a certain kinship with the Korean people as, in the eighth century one of the empresses was of Korean descent. In South Korea it was front page news though the Japanese right was miffed. The Korean connections have long been supported by historians but have never been publicly acknowledged. Indeed, in the pre-war period, books were banned and authors arrested for making such statements.

Similarly in 2004 when the question of singing the national anthem in schools was being debated, Akihito spoke unequivocally. A well-known Japanese chess player said to the emperor that he was working to have the national anthem sung in schools. Akihito replied that he hoped that this would not be made compulsory; another nail in the conservative agenda.

Historically, Japanese emperors have rarely exercised political power, even in the classical period there were very brief periods when they actually ruled. The longevity of the imperial house was really possible only because others exercised power in their name. Historically, they have often been so impoverished that they could not even afford to carry out their enthronement ceremonies.

In the modern period while they were made the centre of a powerful religious nationalism, their movements and utterances were carefully controlled. Today, the emperor is a symbolic head with no political power but continues to carry the onerous burden of myth. The imperial household that manages the emperor, and his family, is a place of rituals and tradition and even though ushering in change must have been very difficult, the institution is slowly changing. The Japanese emperor’s visit is important as Indo-Japan relations develop a greater closeness. He may not be a political figure but he does represent the new Japan with which India, and Indians from all sections of society, need to engage more fully. A creatively productive engagement can be built on a better mutual understanding but only when it is framed within a larger universe of values.

The author is Professor of Modern Japanese History, Institute of Chinese Studies

He may not be a political figure but he does represent the new Japan with which India, and Indians from all sections of society, need to engage fully. But that engagement must be framed within a larger universe of values.