The central government recently declared the minimum support prices (MSP) for 14 kharif crops (or crops which are planted in summer). This includes crops like paddy (rice), jowar, maize, bajra, raagi, moong, urad, groundnut, etc. Of these crops, the government largely buys paddy directly from farmers through the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and other state procurement agencies. The trouble is, even though MSP is valid throughout the country, the government procurement mechanism varies across the length and breadth of the country.

It is good in some places and bad in some others.

This basically leads to a situation where even though the government sets an MSP, in parts of the country where the procurement mechanism is weak, farmers end up selling the paddy they produce at a price lower than the MSP. This beats the entire idea of having an MSP.

The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) studied the wholesale prices of paddy between April 2016 and February 2018. It found that in Uttar Pradesh and Assam, the two states which contribute 17 per cent to the overall paddy production in India, prices were below MSP during the “peak market arrival period of October to December 2017”.

The Commission also found that “prices in West Bengal, Punjab and Haryana were above the MSP, mainly due to the good procurement system that is in place in these states.”

To cut a long story short, the procurement mechanism varies from state to state, and it has an impact on the wholesale price of paddy.

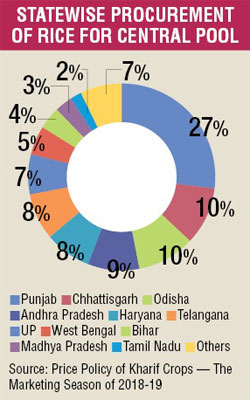

One state where the procurement mechanism is good is Punjab. As the CACP points out in a document titled Price Policy of Kharif Crops — The Marketing Season of 2018-19: “Punjab is the largest contributor to the central pool of rice procurement with an estimated share of about 27 per cent, followed by Chhattisgarh (10 per cent), Odisha (10 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (9 per cent) and Haryana (8 per cent).”

One state where the procurement mechanism is good is Punjab. As the CACP points out in a document titled Price Policy of Kharif Crops — The Marketing Season of 2018-19: “Punjab is the largest contributor to the central pool of rice procurement with an estimated share of about 27 per cent, followed by Chhattisgarh (10 per cent), Odisha (10 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (9 per cent) and Haryana (8 per cent).”

The interesting thing is that the people of Punjab consume very little of the total rice (i.e. paddy) that they produce. Almost all of it is sold in the open market. The government procures a bulk of this marketed surplus.

Of the total rice procured by the government for the central pool in 2016-17, 27 per cent came from Punjab. In 2015-16, this had been at 25.7 per cent.

It is worth remembering here that Punjab is a semi-arid region. Production of paddy requires a lot of water. Hence, the question that needs to be asked is, why is a semi-arid region growing so much rice?

Punjab is the third-largest rice producing state in India, with West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh taking the top two places. Given the fact that very little of this rice gets consumed in the state, almost all the rice produced, is available for sale. The government of India procures more than 70 per cent of this. The larger point being that the farmer in the state has a ready-made buyer in the Indian government. And given this, the system as it is, incentivises him to produce more and more rice, in a semi-arid region.

When it comes to rice production, Punjab is India’s most productive state. Even though this yield has only increased by 20 kgs per hectare in the last 10 years. Punjab produces 3,974.1 kg per hectare of rice. The trouble is it uses a lot of water to achieve this. As The Price Policy for Kharif Crops: The Marketing Season for 2016-17, points out: “If water consumption is measured in terms of per kilogram of rice, West Bengal becomes the most efficient state, which consumes 2,169 litres to produce one kg of rice, followed by Assam (2,432 litres) and Karnataka (2,635 litres). The water use is high in Punjab (4,118 litres) …[This] shows that the most efficient state in terms of land productivity is not necessarily the most efficient when measured in terms of irrigation water.”

This excess production of rice in the state is leading to water shortage. As CACP report out: “Given that this water is extracted by mining groundwater, as is being done in much of… [the] Punjab and Haryana belt (particularly in the case of rice), where [the] water table is receding by 33 cm each year, thereby shrinking its per capita availability.” This is a situation which needs to tackled with utmost speed and sincerity.

The government (both the state as well as the central government) needs to look beyond the immediate gains of the Punjabi farmer. One solution is to gradually move the government procurement of paddy from Punjab to other states. At the same time, the farmers need to be encouraged to grow crops that do not need as much water as rice does. As CACP report out: “Crop diversification from water-intensive crops to pulses and oilseeds is the need of the hour”. Even though, rice procurement by the government has become more diversified over the years, Punjab continues to contribute more than one-fourth of the rice to the central pool. Clearly, Punjab’s share is intact (in fact, it has grown). This, when there are still some rice producing states where enough procurement is not happening.

The writer is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. Views are personal.