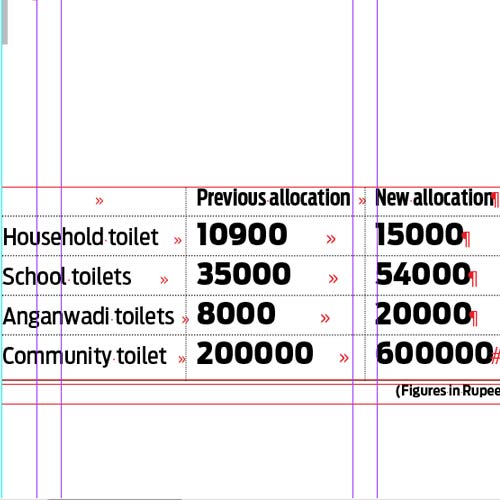

From being the sterile recipient of excreta, the humble toilet has reached the exalted status of being the subject of the Chief Executive’s speeches on every occasion. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has talked of a toilet in every home by 2019 in his Independence Day speech; this culminated in a series of announcements, including the 100-day target of the government to build 52 lakh toilets. The Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS) has put its money where the PM’s mouth is by substantially raising subsidies for the construction of different categories of toilets. It has also announced a new programme called the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (SBA).

Do the figures add up? Yes and no.

The logic behind these allocations is that earlier amounts were too little to make durable toilets. From 1999 to 2006, the government paid a subsidy of Rs500-Rs1,200 per household toilet “often resulting in non-durable toilets which became defunct over the years”. MDWS’s online reporting system says 77.2 per cent of households of people below the poverty line (eligible for subsidy) have toilets that include these defunct units. The Census 2011 says only 32.7 per cent have, while the 2012-13 survey by MDWS puts the figure at 40.4 per cent. The 2012-13 survey of the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) puts it at 40.6 per cent.

The different figures disguise a very real problem.

Over the years, the government has released money for toilets in 84.2 per cent of the BPL houses. But only 40.4 per cent of them exist. So about 36.8 per cent or 3,57,11,000 toilets have disappeared of which about half have been subsidised. At an average cost of Rs850 per toilet, that means infrastructure worth Rs1,518 crore is infructuous; this was either never made or used for other purposes.

A major fault in the programme lies with people who are supposed to benefit. Defecating in the open is a fact of Indian life. An estimated 62 crore defecate in the open every day. That means about 51 per cent of the population. Going by the ministry figures, 49 crore people in rural India out of a total rural population of 88.8 crore have toilets. The number of open defecators should be 39.8 crore, or 45 per cent of the rural population. This implies there are 22.2 crore ‘ghost’ defecators.

There is an explanation for this: Studies from different parts of India indicate the use is very low, at about 35 per cent. Therefore, only about 22 crore people actually use their toilets and 27 crore do not. This puts the number of those defecating in the open slightly higher at 66.8 per cent. These studies also gives reasons that range from the plausible (poor quality of construction) to the implausible (cultural ethos, as if Indians have defecated in the open since time immemorial).

The sanitation programme has been fundamentally flawed since it began, with only a small amount of money to promote hygiene or trigger behaviour change. What was conceived as a demand-led campaign, where people are ‘taught’ about the hazards of open defecation, has become yet another target driven government programme to ratchet up numbers. SBA does not address this systemic flaw and allocations for hygiene or behaviour change remain a small fraction of the total amount.

Performance against the 100-day target has been pathetic. The Ministry issued orders to the states to make 52 lakh toilets against an annual target of 1.25 crore toilets, ie, 41.6 per cent. However, funds release has only been Rs442 crore out of a

budget of Rs3,085 crore, or 17 per cent, that too, to only eight states. SBA sets a target of 1.77 crore toilets a year for the next five years. It seems the 100-day target covering the quarter from May to August was arbitrary and was done before SBA was announced, a classic case of putting the cart before the horse. Not only has the 100-day target been missed, in the process of chasing it the crucial rules that will support SBA have been delayed.

One of the main changes in SBA is severing the link with the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme. The previous scheme provided a subsidy of Rs4,500 and those who built toilets were eligible for Rs5,500 from MGNREGS. This did not work in practice as the agencies administering both schemes were different and the flow of funds was seldom smooth or coordinated. Hopefully by increasing the subsidy and bringing it under a single scheme SBA will speed up things.

The danger remains of SBA becoming target driven. People in the social sector say it take six to eight months to convince a village of the need and utility of toilets. This is time and resource intensive but usually results in better quality of construction and higher levels of usage, sometimes as much as 100 per cent; true, curtailing open defecation is a slow process. This could entail focusing on hygiene as being the central plank for behaviour change both before, during and after the construction of toilets. The approach will have to change from creating a demand for toilets to using them. Most people are aware of the scheme and the generous subsidy for making a toilet; they will comply with the letter of the scheme. They may not comply with the spirit of the scheme which will end up defeating the purpose of making India open-defecation free. In its current form SBA may end up spending around Rs16,000 crore over five years to create more infructuous infrastructure. SBA’s targets do not indicate there is space for adequate hygiene education leading to behaviour change as it is more ambitious than its predecessors. At its height, the earlier sanitation campaign made 1.24 crore toilets in 2009-10 but usage has been poor, at less than a third. Unless there is a course correction at the outset, open defecation will continue to pose problems.

Jacob is the Head of Policy with WaterAid India. White works with WaterAid UK