“Wonderful concert!” I looked at the woman who breathed charm and camaraderie as she congratulated our team after our musical tribute to Mahatma Gandhi in Columbus city, on our US tour this summer. She introduced the man beside her, “My husband Amit.”

That very morning I had found two books in my host’s study: “Dothead”, a book of poems, and “Godsong”, a translation of the Bhagavad Gita, both by Amit Majmudar. I had no idea that he was the Poet Laureate of Ohio, and lived in Columbus.

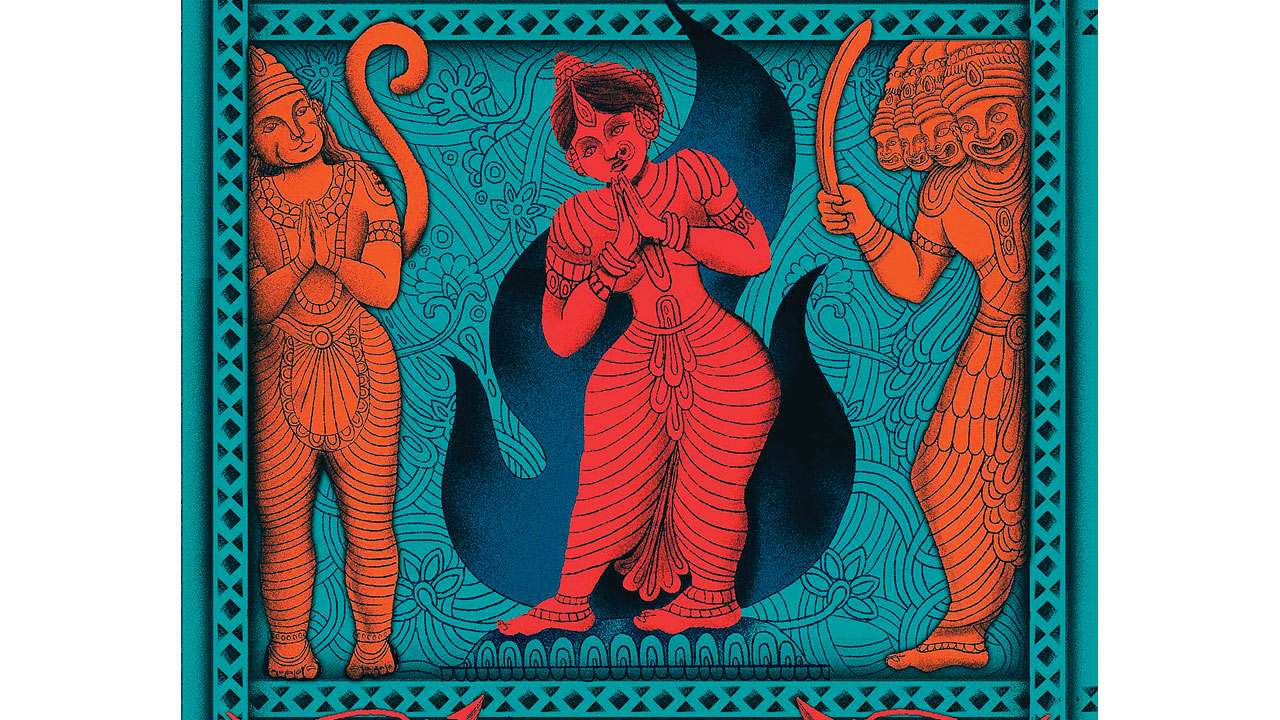

Early this year, diasporic writers Majmudar and Chitra Divakaruni had been invited by literature festivals in India to talk about their new books – both centre-staging Rama’s wife! In Chennai, I had heard Divakaruni discuss the difficulties of shaping a cult figure idolised by a vast community as her protagonist in “The Forest of Enchantment”. In Columbus, I had never imagined I would get to hear the how and why of Majmudar’s “Sitayana”.

As a major mythological character, Sita bears the palm for colourlessness. Objectified by the male gaze of Ramayana writers in every Indian language, Valmiki’s heroine has been shaped by centuries of patriarchal imagination as a “chaste” and “pure” wife, meekly obeying her husband’s diktats. Even in a postmodern graphic novel, Sita cannot be allowed to stray from the ideal of the uttama nayika, the “unimpeachable” ideal of male fantasy. As a goddess worshipped by billions, she is dangerous material for reinterpretation.

When Majmudar found time on a working day for a chat in the park – my first question had to be “Why Sita?” A bluejay trilled in the silence before he answered, “Myths can be reworked endlessly. I don’t want to put people off by indulging in some revisionist or attention-seeking Ramayana for its own sake…. I was true to myself and my readers in Sita’s story, which is ever living, ever changing… My “Sitayana” wrote itself, very quickly.”

“Sitayana” may have been a quickie, but Majmudar’s immersion in the Ramayana began from the days of his residency in medical college. All sleep-deprived free time was spent in wrestling with the architectonics of the epic.

“Years of rewriting kept me mentally alert as I debated on how to find perspectives and structures to retell a story everyone knows” and which he himself knew from Valmiki-Kamban-Tulsidas as also comics and tele-serials.

Starting at the crucial space and time of the abducted Sita’s confinement in the Asoka orchard, “Sitayana” flashes back and forth, overlaid and intercut with multiple voices. Such stereophonic effects combined with panning techniques add pace, perspectives, contrasts, subtexts. “This may sound kooky and loopy, but I was literally taking dictation as the characters talked, including the little squirrel who helped Rama to build the bridge across the ocean. You feel honoured and blessed when that happens.” He adds with a smile, “A gift from the gods for translating the Gita?”

Narrativising style and wordplay remind us that the novelist is also a poet. “Words shape the imagination in a give-n-take partnership, springing up little surprises here and there. I start writing and the different elements of the language start playing, with some spontaneity and serendipity, and chaos gets structured.”

How does Majmudar the nuclear diagnostic radiologist relate to Majmudar the writer? “I produce 15,000 pages of clear, concise technical writing per year as a radiologist (yes, far more than as novelist/poet) interpreting CT scans and ultrasound reports, based on close observation and interpretation. That discipline is invaluable to any writer!”

Identifying with Hindu metaphysical ideas (minus the political affiliations this affirmation would imply in India), Majmudar is interested in all religions. He sees the literary and the spiritual conflating at the centre of his life. A stranger to desi-videsi confusions, he feels no pressure to belong to any larger collective. “Cultural hybridity is part of my individuality, strength and power, enabling me to access more than one culture/civilisation.”

Three forthcoming books underscore concern with dharmic dilemmas. In “Kill List” (Knopf), a collection of verse, the title tells the story. “Downfall” examines three controversial killings in Kurukshetra: Sikhandi killing Bhishma who refuses to fight the transgender warrior, Bhima’s breaking the warrior’s code by smashing Duryodhana’s thighs, and Arjuna slaying the weaponless Karna as the latter is repairing his chariot. “Soar” explores searing ambiguities in a surveillance mission. Here two soldiers (Hindu and Muslim) on a hot air balloon during World War II, become sitting ducks under that massive ball of flammable gas, for the enemy forces they are sent up to spy upon.

Meanwhile Majmudar continues to work on retranslating the Bhagavad Gita - “to do it better”.

The writer’s final words bristle with pride, “Actually, you should be writing about my wife, Ami. Her novel “Torchbearers” is about to come out! It is absolutely wonderful!”

The author is a poet, editor and a translator