With no state to call their own, Thathai Bhatias look at their cuisine as a strong factor that holds the community together.

n the late ‘70s, Mumbai resident Lalit Gajaria and his mother had accompanied his sister-in-law to Arya Vaidya Sala in Kottakkal, Kerala, for a lengthy Ayurvedic treatment. The family carried along their own food ingredients and a cooking stove. Once there, they cooked their own meals and when they almost ran out of something, Lalit would grab a sample and head to the nearest store. He would show this to the Malayalam-speaking storekeeper, gesture he wanted more and thus replenish their food supply.

Though carrying food and a stove to an alien land was a necessity in the ‘70s, the practise is not really unheard of today in the Thathai Bhatia community. Some of the community’s women do not eat food served at hotels or weddings, preferring to carry their own. “I have seen groups of eight or nine women go to a corner and eat their own food from tiffin boxes at weddings,” says Lalit.

Thathai Bhatias hail from Thatta, a small town near Karachi in Pakistan. The community is often inaccurately described as being a Sindhi sect. “But we are followers of Krishna and are Pushtimarg Vaishnavas,” explains Lalit. Also, while most Sindhis are non-vegetarians, Thathai Bhatias are strict vegetarians.

Onion and garlic are banished from the kitchen of a Thathai Bhatia family — some even refuse to let in a loaf of bread. “Earlier, bread was made by Muslims and the kneading of the dough was done by foot,” explains Lalit. But religion has very little to do with the restrictions, he adds. This is more of a cultural practice.

Eighty five-year-old Sita Bhai Haridas, a Dubai-resident for 25 years, is yet to taste chocolate, biscuit or bread. She always carries her own water and food, even while travelling. “When I grew up in my village in Karachi, we never had chocolates, cakes or biscuits. Why should I begin now?” she questions. Her son, Kishore Bhatian, 67, says that the need to follow the practice has diminished over the years, with every generation. “The children in my house like to order out, especially pizza. The main kitchen is for the entire family but when they bring the pizza home, they have to eat it in the pantry,” explains Kishore.

Home cooked traditions

Back at the Gajarias’ two-bedroom apartment in Kemp’s Corner, South Mumbai, Lalit’s wife Chandra Gajaria, 66, is bent over the stove making tuk, an authentic Thatia Bhatia dish served as a side dish or an accompaniment. She deep fries cut potatoes and yam on a medium flame till half done, waits till they cool down, flattens them between her palms and then puts them back into the fire. “Once crispy, you can sprinkle them with salt and red chilly powder,” explains Chandra.

My eyes, however, are on the dish with a deceptively simple name: Bhatia kadi. This kadi takes a whopping four hours to get cooked. It is an assortment of vegetables like drumsticks, yam, ladyfinger, bananas, potatoes and other ingredients like jeera and fenugreek seeds, channa and cluster beans cooked in a thick, delicious broth. Chandra insists that it is not as complex as it sounds. “You don’t have to crush anything … the vegetables are added in stages. The longer it is kept to boil, the better its taste,” she explains. The vegetables are cooked to perfection and blend in seamlessly with the rich gravy.

A typical Thathai Bhatia lunch includes chappati or puri, rice or pulao (consumed before the chappati/puri), vegetables, a kadi or dal, salad or fruits and curd, dahi ki kadi or buttermilk. Rice is cooked with salt and later with ghee on dum and served with lentil toppings like crushed moong dal, moong dal cooked with ghee or crushed or whole urad dal. The authentic Bhatia puri is made from red rice, also called Patni rice. “We don’t roll the dough using the rolling pin. We do it with our hands,” explains Chandra.

one cuisine to bind them

With only about 10,000 Bhatias remaining worldwide, Dubai-based couple Bharat and Deepa Chachara look at Thathai Bhatia food as something that has stood the test of time and united the community. In 2002, the duo launched a website Panja Khada (our food) which is believed to be the only website on the cuisine. The website includes recipes, explanation of various culinary terms and other useful tidbits. “Last month we created a Facebook group called Bhatia Buzz. We had a competition asking people to share tips on how to use leftover food. In five days, we got about 86 recipes from India, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, Dubai and so on.”

Bharat is pleased that most respondents were below 40 years of age. He agrees that most youngsters tend to lean towards fast food, but insists that they are aware of the cuisine and are using it as a base for fusion. “The cuisine is evolving,” laughs Chachara. “Don’t be surprised if you see Bhatia pizza in Khana Khazana!”

Batatay ja Tuk

Ingredients:

3 to 4 large potatoesl Oil, 1/2tsp salt, 1/2tsp red chilli powder, 1/4tsp black pepper powder (optional)

Peel the potatoes and cut them lengthwise into two. If the potatoes are very large cut them into four. Potatoes can be replaced with yam (suran ja tuk), raw banana (kache kela ja tuk), sweet potato (taraylo mitho gajar) or colocasia (arwi ja tuk).

Heat the oil for frying on a medium flame. When hot, deep-fry the potatoes. When they are half done, remove and allow them to cool for five minutes. The potatoes can also be par-boiled.

Flatten each half-fried potato with the palm of your hand. They will become round and cracks will appear on the potatoes’ surface. lFry the potatoes again in the oil on a medium flame till crisp and golden brown. Sprinkle with salt, red chilli powder and black pepper powder. Serve hot.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

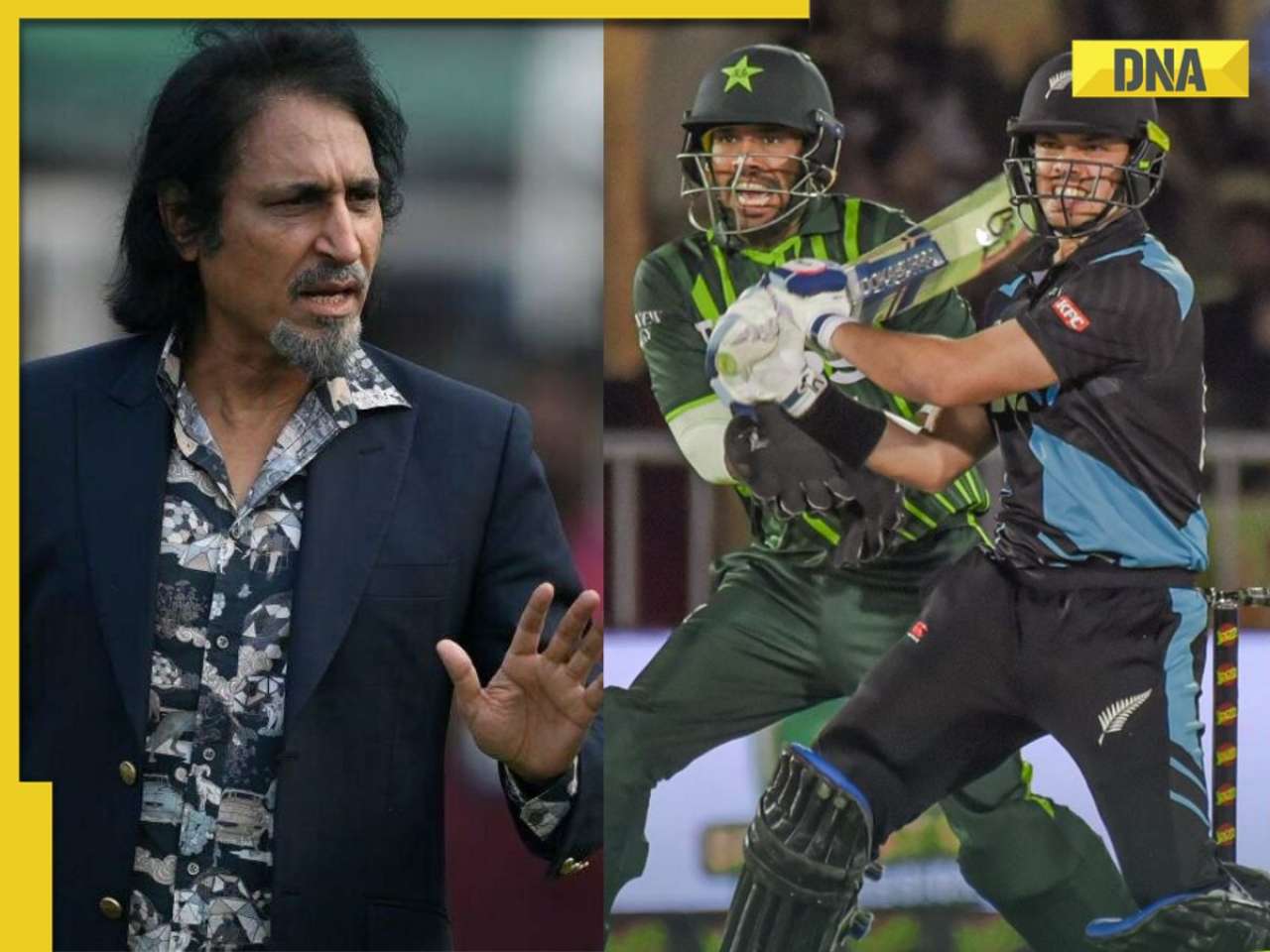

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

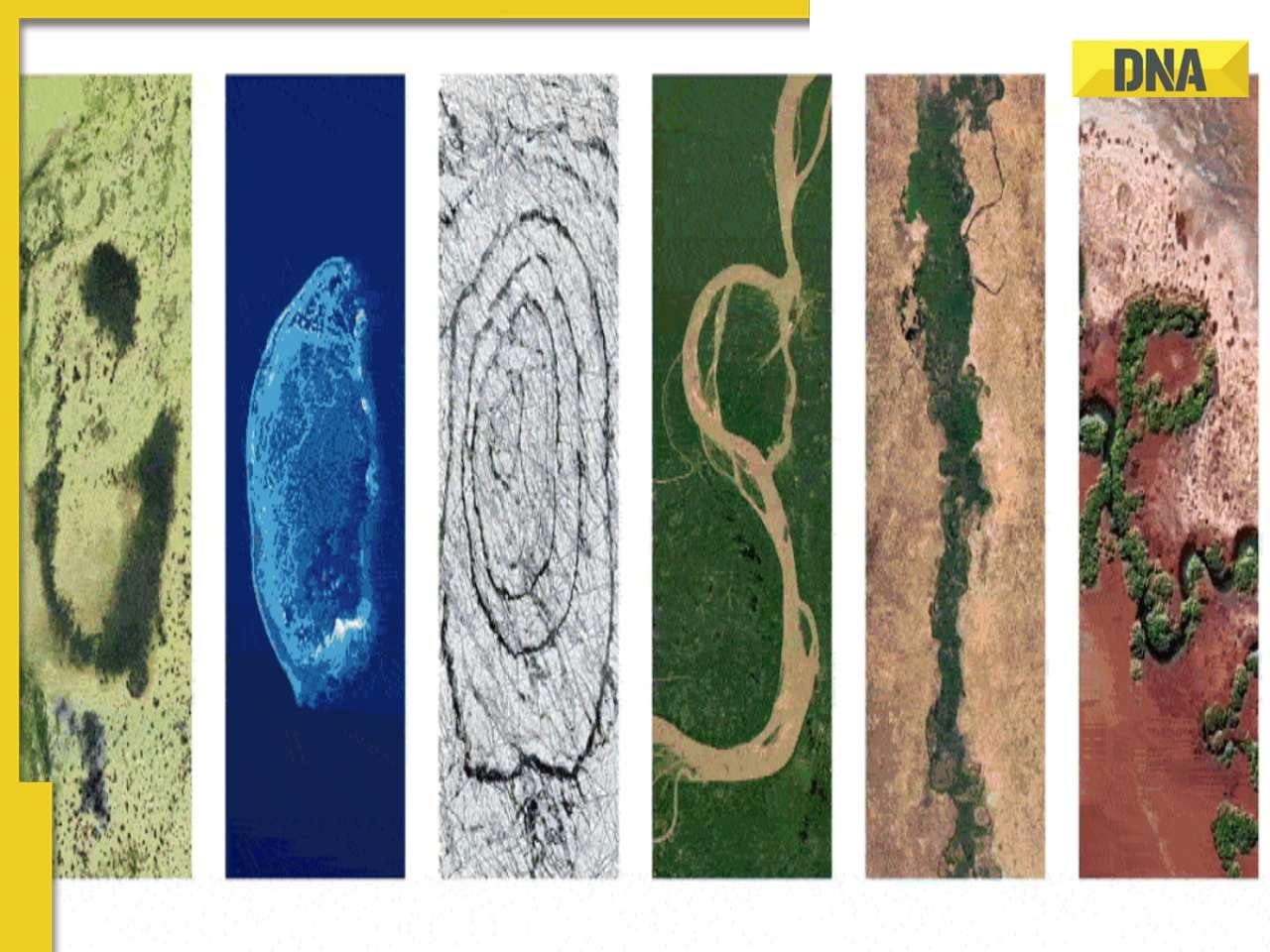

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)