The image of Mahatma Gandhi at the charkha is one of universal appeal. It was after all, through this one symbol that he brought the entire nation together under the banner of Satyagraha. Spinning one’s own yarn, weaving one’s own cloth and making one’s own clothes not only ensured that the market for British mill-made cotton faced a major setback in India, but also brought the masses into the fold from all corners of the country. In a brilliant socio-political manoeuvre, farmers now had a solid role in the movement.

Yet, as the nation prepares itself for a celebration of the Mahatma’s 148th birth anniversary, one cannot deny that the cotton farmers have fallen out of the sustainable cycle of khadi, just as the demand for khadi itself has exponentially reduced with the introduction of foreign and synthetic material.

“Khadi is an industry with zero carbon footprint, because it is handspun and handwoven,” says the chairman of the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC), VK Saxena.

However, while this may be true, strictly in the production sector, the introduction and subsequent spread of BT cotton (a genetically modified variety of cotton inherently detrimental to the soil and heavy on the farmer’s pocket) in the agricultural sector keeps it from being “true khadi” as activist Vandana Shiva calls it. “Gandhi would not have allowed BT cotton into his fabric,” she asserts. “But, how can the supply to khadi weavers be organic without a concerted effort to make sure the cotton is organic?”

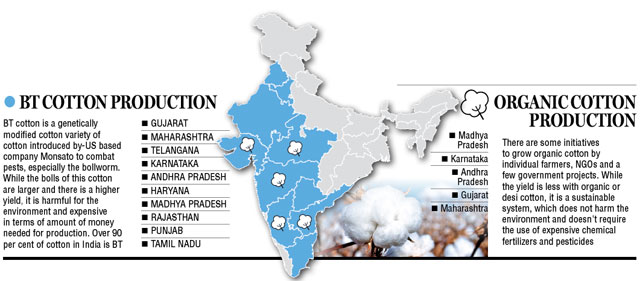

According to a report by the The Cotton Corporation of India published in 2013, over 90% of India's cotton land is dedicated to growing BT Cotton. The seeds of this strain of cotton, which is resistant to the green bollworm menace, is produced and distributed by a USA-based MNC, Monsato at the beginning of each planting cycle. “Thus, not only do farmers have to buy larger amounts of fertilizer needed for this GM cotton, but they also have to buy seeds each season, as opposed to desi cotton, in which the yield included seeds for next year's crop,” explains Andndateertha Pyati, an environment journalist and cotton activist.

According to a report submitted by cotton activist and director of Ahmedabad-based NGO, Jatan, Kapil Shah to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Science & Technology, Environment and Forest on 16th January, 2017, “Each and every cell including root tip, flower bud, ball and seeds produce toxin and there by it adversely affect the farm ecology. Not only root exudates, but also the residue of the plant also emits toxin while decomposition of plant tissue.”

And while the plant was initially brought in to ensure a reduced usage of pesticides, many insects have developed a resistance, leading to the creation of super pests. The pink bollworm became such a menace that in 2017, farmers faced major losses due to massive infestations.

In Vidarbha, tragedy struck as more than 40 farmers allegedly passed away due to passive pesticide inhalation in 2017. In other districts, such as Yatmal, farmers, unable to bear the loss of the 2017 crop failure and faced with difficulties in the process of getting the government grants granted last year, committed suicide before the 2018 cotton season.

Shivdas Patil, a cotton farmer from the Jalgaon district of Maharashtra also felt the pinch last year when he lost the majority of his cotton crops to the infestation. “We lost 60 takas of cotton to the pest, only 40 were salvageable and brought less in the market since it was inferior to the produce found in other years,” he laments.

The risk factor with BT is high. While the high yields and bigger boll size are lucrative for farmers, explains Patil. However, low produce mean that the investment made in the form of expensive seeds, fertilizer and pesticides leads to heavier losses than desi varieties. “A lot also depends on rainfall. Without enough water, or too much rain during plucking season, there is always a risk for losses being incurred.”

While the woes of the farmers cut deepest in the cycle of creating textile, it is not the only complication surrounding khadi. The KVIC defines khadi as cloth that “is hand-woven using hand-spun thread,” according to Saxena. However, many a time, factory-made cloth is passed off as khadi. Customers are fooled, since the texture of this fake cloth is rough, which most mistakenly think is the way to gauge for khadi. “It can only be detected by the twist of the weave as to whether cloth is khadi or not. But that can only be detected using machines; the layman would not be able to tell the difference,” says Saxena, adding that they have issued notices to over 286 institutions and local khadi bhandars for passing off mill-made cloth as khadi. The most notorious of all these, perhaps is the ethnic clothes and accessory giant Fabindia. “We have filed a case against them for using mill-made fabric and have filed a suit of Rs 55 crores for compensation,” says Saxena. The case is still on, and resolution does not seem to be near.

((Left) A weaver weaves khadi cloth from hand-spun thread; (Right) Shivdas Patil, a farmer from Jalgaon in Maharashtra)

It is not only in weeding out of contamination that the KVIC has cleaved a path for khadi over the past five years. While khadi weavers and thread spinners used to have miserable working wages, earning only Rs 4 per 100 metre of thread spun from cotton, the clusters brought under KVIC purview over the years have seen a marked improvement. “ In 2016, we increased the price from Rs 4 to Rs 550 per 100 m of khadi and further increased it to Rs 750 this Independence Day,” says Saxena. This means that the wage of these workers is an approximate of Rs 200 per day, a much more respectable salary to draw than even two years ago.

The industry itself has grown exponentially over the last four years – 133% as opposed to its 6.8% growth from 2004-2014. While in 2015, khadi only constituted 0.26 per cent of the whole textile industry, as of 2018, it has become 0.88 per cent.

However, the chairman himself admits that despite efforts to the contrary, BT cotton is used even by KVIC weavers to make khadi. “In some parts, we do use organic cotton. For instance, In Andhra Pradesh, we use organic cotton for the Kunnuru khadi, which is a heritage khadi. We also use organic cotton in our tribal areas,” he says, but laments, “Since were are not in the farming department, we cannot oversee the fact that all the cotton coming in is organic.”

Aside from government initiatives, there have also been initiatives taken by several NGOs to grow cotton using organic farming. “These efforts have been taken in Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, pockets of Maharashtra, but are still very niche,” says Shah, whose own NGO, Jatan works towards production of organic cotton. “There have also been efforts by many agricultural scientists to create local strains of BT cotton, but none of these are in the market as of now.”

In and around the small town of Musiri in Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, the Digital Empowerment Foundation, which is working on empowering weaver clusters with new computer technology for marketing and design, carry organic cotton for the weavers to use. Founder-director Osama Manzar says, “It is not a khadi initiative as we source the yarn. But we source organic yarn for Musiri and are planning to do the same for all our clusters within the year.”

In terms of economy, the khadi still needs to be able to stand on its own without constant backing and supervision from the government and NGOs. For this to happen, the marketability of the product needs to increase. Haresh Shah, ex member of KVIC, and trustee of multiple NGOs including Yusuf Meherally Centre (YMC), Mumbai Khadi & Village Industries (MKVI) and Vaikunthbhai Mehta Research Centre for Decentralised Industries (VMRCDI), who has tried ways to make khadi clothes more appealing to the youth, laments that most people do not understand the value of the cloth. “I wanted to create a market for khadi, which the impulse buyer could simply pick up, not something that is so highly priced that they would think twice,” he recalls. However, he often faced problems from consumer websites that were unwilling to promote his clothes since the fabric is not as perfect as loom-woven fabric. “This is the mentality that needs to change. But it is difficult to bring this change. When you go to a Sabyasachi or Ritu Kumar or a similar high-brow designer label and spend huge amounts of money to buy a khadi garment, it is not for the fabric but for the label that you are investing the money. The marketability of the fabric itself remains low.”

One possible solution towards promoting khadi that makes use of organic cotton, he says, can be to demarcate khadi cloth according to premium and regular, with khadi made from organic cotton being offered at premium prices, and a proper campaign to back it up. “There could be a demarcation of khadi according to the variety of cloth used and the design,” he explains. “You could have an affordable variety, as well as a more premium variety for the elite.”

For khadi to be marketable, the youth needs to become a part of the buyer circle. One way to do this is to bring the cloth into the 21st century, as has been seen in recent efforts by some fashion designers. “While the youth would be more than happy to wear a garment made from heritage cloth (which khadi is), they would only wear it if the garments are attractive,” says Jawahar Singh, co-founder of Avishya.com, an online portal for handcrafted clothing and accessories, who tout the use of organic cotton for their clothes. Alongside sarees and kurtas, modern garments would help increase the market value of khadi. The cloth itself could also be dyed in a rainbow of attractive colours instead of sticking to the conservative white of pre-Independence India.

A second possible step is to have more mid-range garments, as Shah had tried to conceptualise.

A middle ground is what Singh says brands should aim for. “The problem is that you have a few designers making say 20 exclusive designs and marketing them at exclusive high-end boutiques. Or you have khadi mandals, where subsidised garments are sold. But most of the youth are looking for an in-between. If you have more mid-level brands say at the same level Fabindia in the market, it would be possible to bring khadi into the mainstream,” he says.

Ultimately, it is the division between industries that seems to be at the root of the cotton-khadi problem. One cannot technically call khadi non-sustainable in itself. However, with 90 per cent of the cotton in the country being grown using methods detrimental to the environment and farmers, the entire textile industry is being backed by a system which is the very opposite of sustainable. Hence, khadi, too, cannot escape this cycle.

With no integration between departments in the government, sustainability cannot exist across boards. Like the Niti Ayog initiative in the health sector, which is an umbrella agency working across the health and nutrition sectors, a similar move in the textile industry, which would look at the matter holistically, can be a possible solution.

And so, the debate continues...But as Pyati succinctly says, no matter the market value, or the industry improvements, with BT cotton still at the helm, “this is not the kind of industry that Gandhi, as a man who was an advocate of all things indigenous, would have envisioned for India.”

Note: In the story How sustainable is Khadi? carried in the September 30 issue of JBM, Smita Mankad has mistakenly been given a designation as leader of Organic India’s True Wellness Initiative. She does not represent Organic India or Fabindia in any way. We apologise for the error. The story neither attacks KVIC nor FabIndia in anyway.