Mathew Siemiatycki, Associate Professor of the Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University of Toronto, teaches and researches on infrastructure planning, financing and project delivery. He has carried out studies on transportation plans and projects in many global cities, including Delhi. In an exclusive, wide-ranging interview with K Yatish Rajawat, he talks about the challenge of city planning and why silo planning for the cities is not working out

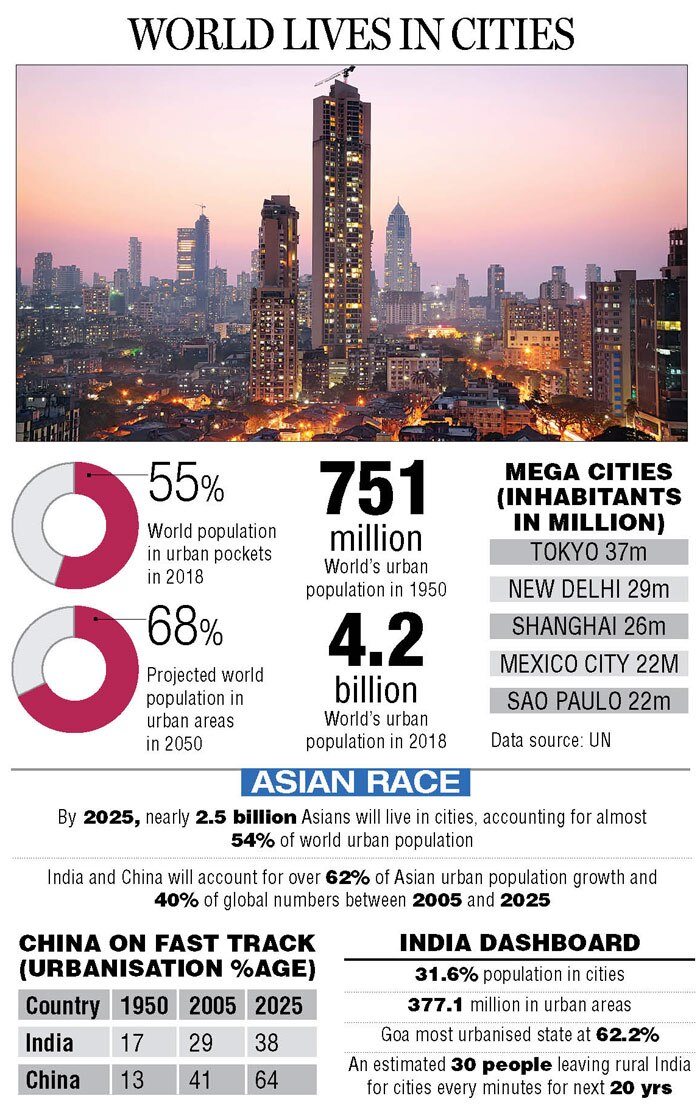

More than half the world’s population lives in cities. Cities are the sites of great opportunities. That is where employment is booming and innovation is happening. But cities are also facing great challenges of inequalities and un-affordability. They are facing challenges around their natural environments, whether it is related to resilience and sustainability or wild fires and personal health from air pollution. They are facing challenges in terms of transportation and how people move around, how the infrastructure grows and issues revolving around culture. This cannot be addressed by a single discipline hence the University of Toronto (UoT) is creating a multi-disciplinary School of Cities.

The way we have examined, studied and understood cities, they have really been in silos. Within city governments and within universities, we have urban planning departments, architecture and business schools. We also have engineering schools to ensure that the structure is functional. Each of these tends to operate in individual silos. This is true of governments and the private sector as well. The real opportunity for the University of Toronto is to create a hub and venue where we can create a new way of understanding the city that’s multi-disciplinary. Start from the foundation that cities require multiple skill sets and require people to have a broad understanding of the relationship between the economies and environment.

The University of Toronto has 250 faculties to do research on cities. The School of Cities has urban planning in geography, political science, history, music, economics and whole host of other programmes. Then we have architecture, engineering and schools of law & management. These are the founding partners. We also have relationships with the School of Proper Health with the School of Social Work as well as the others. So, the University of Toronto is a very large urban institution. What the schools allow us to do is to bring together and provide a hub for collaborations to take place, while also training students in a multi-disciplinary way.

In the academia, the city has been traditionally studied within a discipline, which has its own language, journals and their discourses. But the reality is that the way the faculties conduct their research and the robotic way of research is different. Unlike the academic side, our attempt at the School of Cities is to create this hub that brings together people early in the process and creates collaboration. It is about increasing this collaboration across disciplines and to start thinking about urban problems in different ways. Take the example of a project like cities by design. It entails bringing together an inter-disciplinary group of scholars to design a city intelligently and to get city planners together with architects. The city planners and the architects will plan at the regional and district scale along with the landscape architects. Together, they will converse with people who understand the working of public and private finance. This is a very different approach on how to build cities. I think it is this inter-disciplinary approach, which provides the academics with a venue that will be able to really move beyond the silos that have traditionally challenged urban research.

We want to create a relationship that allows us to do real world research and work with organizations in the public and the private sector in order to understand the genuine challenges on ground. You seek that knowledge and data and in turn, feed that knowledge/data information back into the way decisions are made. So, we are working in partnerships and creating collaborations with municipalities, private sector firms and non-governmental organizations. We want to be on the ground floor as they start to develop their plans, their ideas. We will sit with them and involve them in discussion and provide inputs from our academic experiences as well.

The process is still in the development stage, but to give you an example, how do you set the price publicly and what’s the impact on transit usage the way transportation systems are priced? What we are looking to do is partner with the transportation agency, which has a digital fare card, and with the fare card, we can work with them to see how changes can be made in their fare structure. It can help create positive financial benefit for the users and for the private sector.

This is a project that we are working to develop. I have used this as an example of the kind of project we want to develop. Another scheme involves working with a startup company that wants to move into the challenge economy. Our effort is to see how such companies work in collaboration. What would be the responsible way of entering into new markets? So again, these are in the development phase and are not finished products.

(Siemiatycki continues) Another example is the working of community groups, who are trying to deliver very large scale projects as well as some very local ones, but whose impact is enormous. We are looking to collaborate with such folks and organizations for undertaking such projects. You can do research on such projects and then use that information to demonstrate how to actually programme public spaces. How do you ensure that there is social inclusivity, diversity and that other objectives associated with small scale building initiatives are met? We will partner with them, provide evidence and then take the best idea and scale those up.

I see technology as one part of the puzzle, but not the entire story. I think that this is really the key point, because there are folks who feel that cities are a technical problem to be solved. I come from an urban planning background and I think cities are made up of people who are a complex social species in a critical environment. There is a relationship between people and the technologies.

No. I think that’s a very useful feedback but what I would say is that this multi-disciplinary approach brings urban planning and a host of other understanding of the social environment. We have scholars at the university who have been researching very locally, including myself, on how change takes place and how commutation engages on the ground. I have written papers on the Delhi Metro for example and the way that project was built, but it was something more than just a transportation project. The symbolic message of that project and the way it was rolled out, it became very contentious. What we bring to the table is this recognition that cities aren’t just a technical enterprise.

Yes. Okay. That’s very important, your comment about engineers. I think that’s really the history of how engineers have proceeded and in many contexts, how cities have been planned.

Yes.

Hmm…

I agree with you and I think you are exactly right. I think that cities are often seen as a capacity issue and we are typically focused on the supply side. How do you increase supply to keep up with the demand? The phenomenon that you described will increase demand. You can’t build your way out of the congestion problem and you can’t build your way out of the crowded city problem. At the University Of Toronto, we have some leading thinkers on that matter, including Prof. Eric Miller from School of Engineering who has done some pioneering work on the issue of huge urban demand. City building is a government function, but it is also very much bottom up. So I completely agree with you that this idea that you are going to build your way out of traffic congestion problems or issues around water or energy as capacity is a bit misplaced. Capacity has to be expanded and building infrastructure is needed, but it is more about planning solutions.

At the moment, we are going to be engaging students on a host of educational degree programmes. Some of these activities will revolve around training and leadership, professional education and how you increase technical knowledge to broaden the understanding of city building amongst practitioners. We are also trying to work with younger people to give them the skill sets, as they move into a career in city building.

I think you are right. We spent a lot of time in the build up to the launch of the School, involved as we were in internal discussions with whole set of universities around. What do they mean to have a School of City? And I think, it’s really about learning a new approach. It is for all of us in our own disciplinary silos…

For feedback and inputs, please write to editor@dnaindia.net