The general elections 2019 is moving towards closure, with six out of seven phases already over. All eyes are now on the counting.

It is not surprising that the issue of counting of Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trails (VVPATs) has become hot once again.

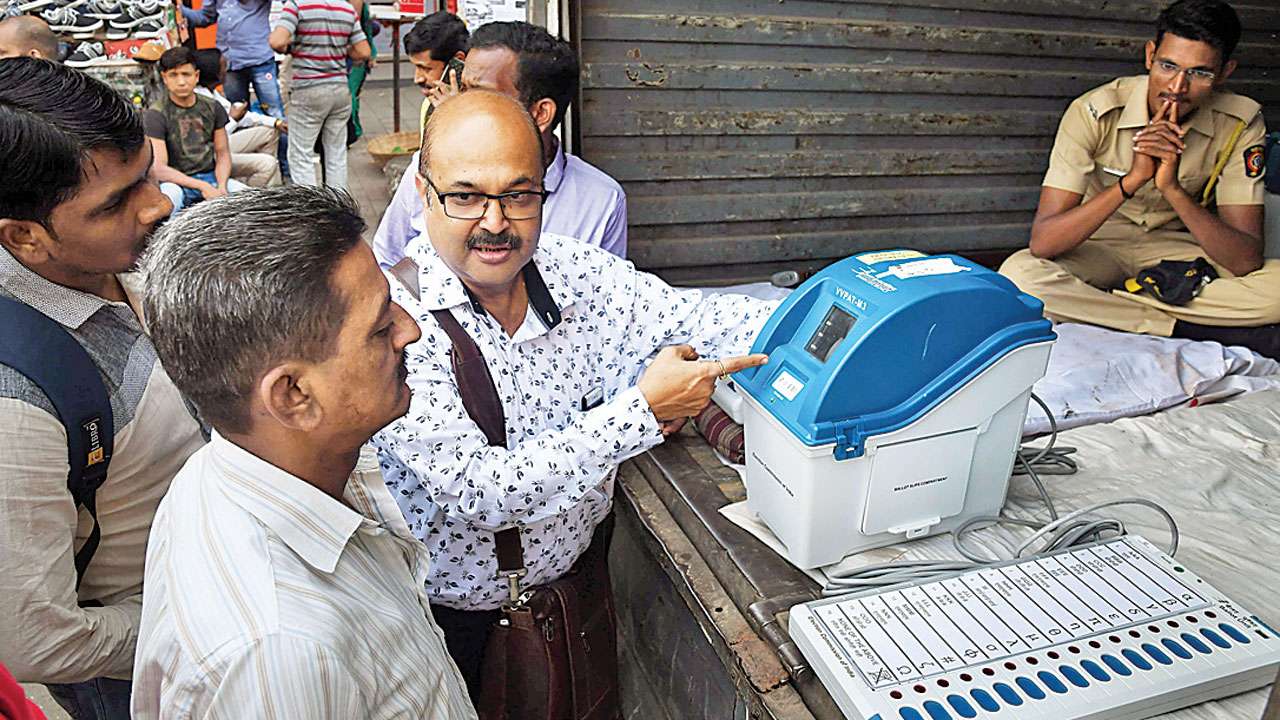

The decision to introduce VVPATs as a measure to make electronic voting machines (EVMs) transparent was taken in 2010 when a meeting of all political parties arrived at a consensus that this was the ultimate answer.

Finding the suggestion reasonable, the Election Commission (EC) immediately accepted it and asked the two EVM manufacturers, BEL and ECIL, to design the VVPAT machines. An independent committee of experts consisting of five professors from different IITs was tasked to oversee the design and the manufacturing process.

A series of trials were held, followed by a full-day election simulation in July 2011 in five climatically diverse cities– namely Cherrapunji, Delhi, Jaisalmer, Leh, and Thiruvananthapuram.

Since many bugs were noticed, the trial was repeated after addressing them in July 2012 at exactly the same places. Only after making sure that they were technologically sound and climatically dependable, were the VVPATs initially deployed in 20,000 polling booths successfully. Subsequently, all constituencies were equipped with VVPATs.

In 2013, the Supreme Court also lauded the EC’s decision to use VVPATs and directed the government to release adequate funds for their procurement for the 2019 elections. The machines that kept coming in were randomly deployed. From 2017 onwards, all state elections have been conducted with EVMs attached with VVPATs.

What was the counting procedure? Slips generated by one VVPAT in each assembly constituency were counted. Of the 1,500 machines counted so far, according to the EC, not a single mismatch was found.

In various elections, however, many VVPAT machines malfunctioned. The chief election commissioner (CEC) righty clarified that malfunctioning is different from rigging.

During the by-elections in Bihar and UP, and the Karnataka assembly elections last year, VVPAT glitches resulted in machine replacement rates of 4 to 20 per cent.

These were largely due to issues in the print unit, which is sensitive to weather. With hardware changes introduced in the machines, the glitches came down to 2 per cent for the Chhattisgarh Assembly elections.

While the debate is going on, I had offered an out-of-the-box solution: Let the top two runners up in every constituency choose any two VVPATs to be counted. As they have the highest stake in the results, they will choose the ones they are most suspicious about.

This is analogous to the Decision Review System in the game of cricket, in which two referrals are allowed for each team. Ever since its introduction, violent disputes about the controversial decisions taken by the umpire have all but disappeared.

This would do away with a large random sample being demanded at present, as only four machines will have to be counted per constituency. In case any mismatch is detected, all machines in the constituency must be counted.

In March, as many as 21 opposition parties moved the Supreme Court demanding that 50 per cent of the total slips be tallied. The SC asked the Commission to increase the sample size of the tally from one booth per assembly constituency to five assembly segments of each Lok Sabha constituency “for better voter confidence and credibility of electoral process”.

The court said that the move will ensure the “greatest degree of accuracy and satisfaction” in the electoral process.

On April 24, the same 21 parties approached the SC again with a review petition, citing concerns related to the first two phases of polling and the “unreliability” of the EVMs.

On May 7, it was turned down with the court saying that “we are not inclined to modify our order”.

I wonder how these parties expected the apex to review its decision, which was taken after great deliberation, when no new facts had emerged justifying the return to the court.

Surprisingly, the issue which should have been discussed and debated is still unattended: What happens if the VVPAT count doesn’t match the EVM count? Even one mismatch is enough to create doubts about the other machines as well.

The current provision is that if there is a mismatch, the VVPAT will prevail. This is fine if the mismatch corresponds to the figures of the mock poll, which have not been deleted.

In all other mismatch cases, perhaps all machines in the constituency should then be counted. The apex court has called for “better voter confidence and credibility of the electoral process.”

If it takes time, so be it. After all, that was the purpose behind the introduction of VVPATs. This can be tried out on a pilot basis. There may not be many such cases, if at all, as evident from the experience of 1,500 machines, which didn’t throw up any mismatches, but public confidence will be ensured.

The Commission may convene an all-party meeting, yet again, as concerns are serious and the stakes extremely high. My experience in dealing with political parties is that with open-minded dialogue, consensus does emerge. Clarity of procedures is required before the counting day approaches. Time is running out.

Writer is former chief election commissioner of India and the author of An Undocumented Wonder- the Making of the Great Indian Election.