While China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been in the news for a while, Japan is slowly funding the building of supplementary trade corridors in the Mekong region, projecting itself as not only interested in building infrastructure but also trade facilitation through human capacity building in the region. With a growth rate exceeding 5 per cent and a combined population of over 240 million, the Mekong region, which was devastated by the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s, has now emerged as a new growth centre of Asia. With the exception of Thailand, the population of the region — that also includes Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam — is young, with more than 20 per cent of its residents below 15 years of age. In 2015, the combined total GDP in the region amounted to $673 billion, and the middle classes are growing right across the region. Japan’s renewed interest in the region is fuelled by Prime Minster Shinzo Abe’s enthusiasm for the US-inspired ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’, which also ropes in India and Australia. China views this as a strategy to contain Beijing’s economic rise and increasing political clout in the region. Under Japan’s new initiative that has targeted mainly Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam, it is not only funding building of highways, railways and bridges, but also trade facilitation through the training of human capital for better flows of people and goods. A major criticism of the BRI has been the emphasis on the building of infrastructure and the lack of attention to building human resources in the countries concerned.

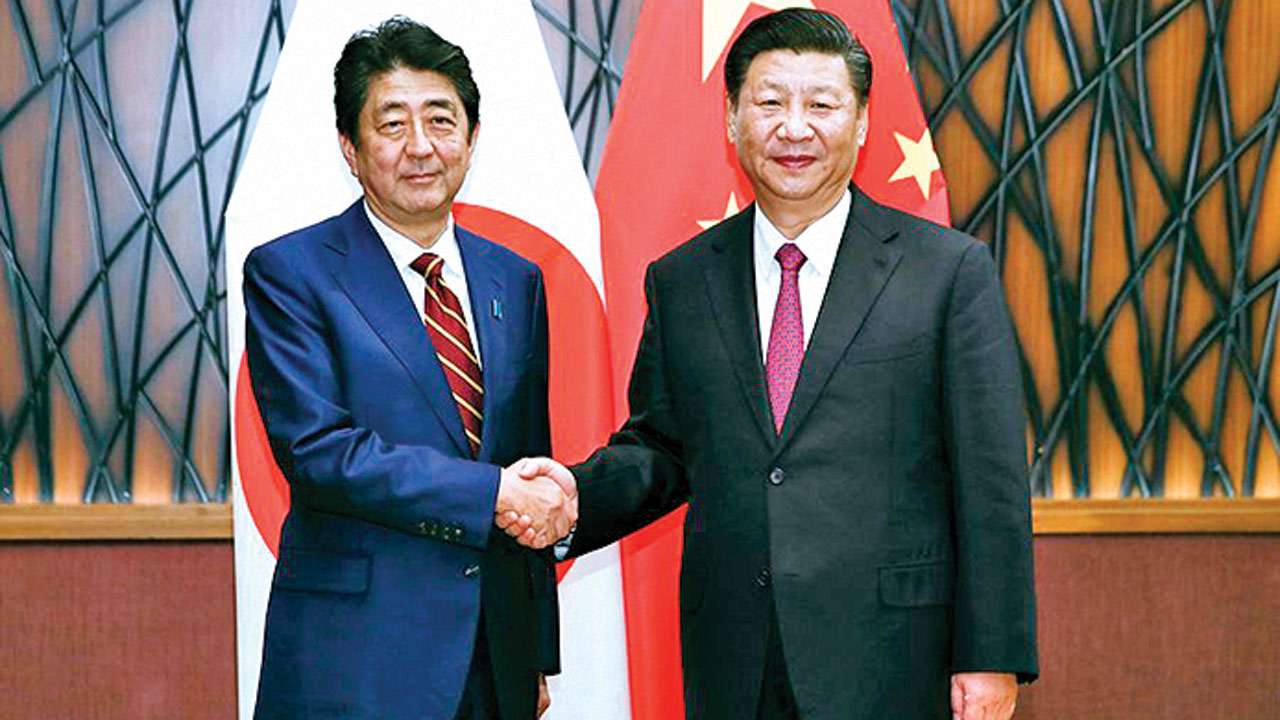

This has led to suspicions that China is building these trade routes for its own benefit and not to promote two-way trade. The ASEAN, whose membership includes all the Mekong countries plus five others, is worried that the increasing rivalry between Asia’s two major powers may sideline the ASEAN-centrality strategy of the regional grouping with respect to development issues. During the ASEAN Foreign Minister’s meeting in Singapore in August 2018, it was emphasized that the ‘Indo-Pacific’ strategy should respect ‘Asean-centrality’ in building the regional economic architecture. At the same meeting, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China would welcome the Japanese initiative for security and economic cooperation in the region, but warned that it needs more funding than what Japan is offering. The Japanese government has pledged US$ 110 billion towards ‘high-quality’ infrastructure projects in Asia. The Chinese government, over the last few years, has pledged some $4 trillion for numerous infrastructure projects in developing countries, that has the potential to make Asia the centre of the global economy. When China announced its grand Silk Route revival initiative (later renamed BRI) a few years ago, Japan expressed scepticism. But in May 2017, Abe sent a special envoy to the BRI forum in Beijing. And at the Hamburg G20 summit in July 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Abe met and discussed Japan’s interest in collaborating with China in implementing the BRI. While perceived disputes in the South China Sea have global attention, there is a greater conflict brewing along the Mekong river, where China has formed its own Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) organisation.

At the 2016 MLC Summit, China pledged $10 billion in preferential loans and another $10 billion in credit for the five countries to develop the region. It has triggered some 132 development projects in the region, but that includes building dams along the river that has upset Vietnam which is downstream. “It is impossible to discuss the LMC without putting it into the context of the BRI. The Mekong sub-region represents a key area for the BRI,” argues Nguyen Khac Giang, lead political researcher at the Vietnam National University in Hanoi. He points out that the so-called “signature projects” of the LMC, such as the Kunming-Bangkok road, China-Laos railway and Long Jiang Industrial Park (in Vietnam) are in the BRI framework; and most of the finance for LMC projects will come from China, either through the LMC special fund or the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund.” The link with China’s ‘initiative of the 21st Century’ indicates that the LMC is part of a bigger bid by Beijing to seek a leadership role in the region, notes Giang. In the 1970s, Japan was credited with having helped the development of South East Asia with strategic investments in setting up industrial parks, where Japanese companies set up manufacturing plants to make use of the region’s cheap labour.

China began its investment in South East Asia much later and started committing funds for infrastructure development after 2000. China’s initiatives for connectivity gained momentum in 2013 when President Xi Jinping proposed the BRI.

“In the colonial past, the Mekong region was divided between two rival powers: Great Britain and France,” notes Furuoka. “With recent developments, the Mekong countries may want to work out an astute and ingenious diplomatic policy to counteract potentially contradicting interests in the region. Otherwise, they could once again find themselves becoming a ‘playground’ for rival powers in Asia,” he warns.

The author, Head of Research, Asian Media Information and Communication Centre in Singapore, is a journalist. Views are personal.