The problem with history is that it is often nuanced. Therefore, Rahul Gandhi’s colourful barb at NaMo’s China diplomacy in the Masood Azhar episode case might resonate with those bashing PM Modi, but betrays deep historical ignorance.

Such ignorance adds up because graver implications of past mistakes cannot be undone.

It is a fact that India was a founding member of the United Nations, whereas mainland China was excluded from that body until the early 1970s.

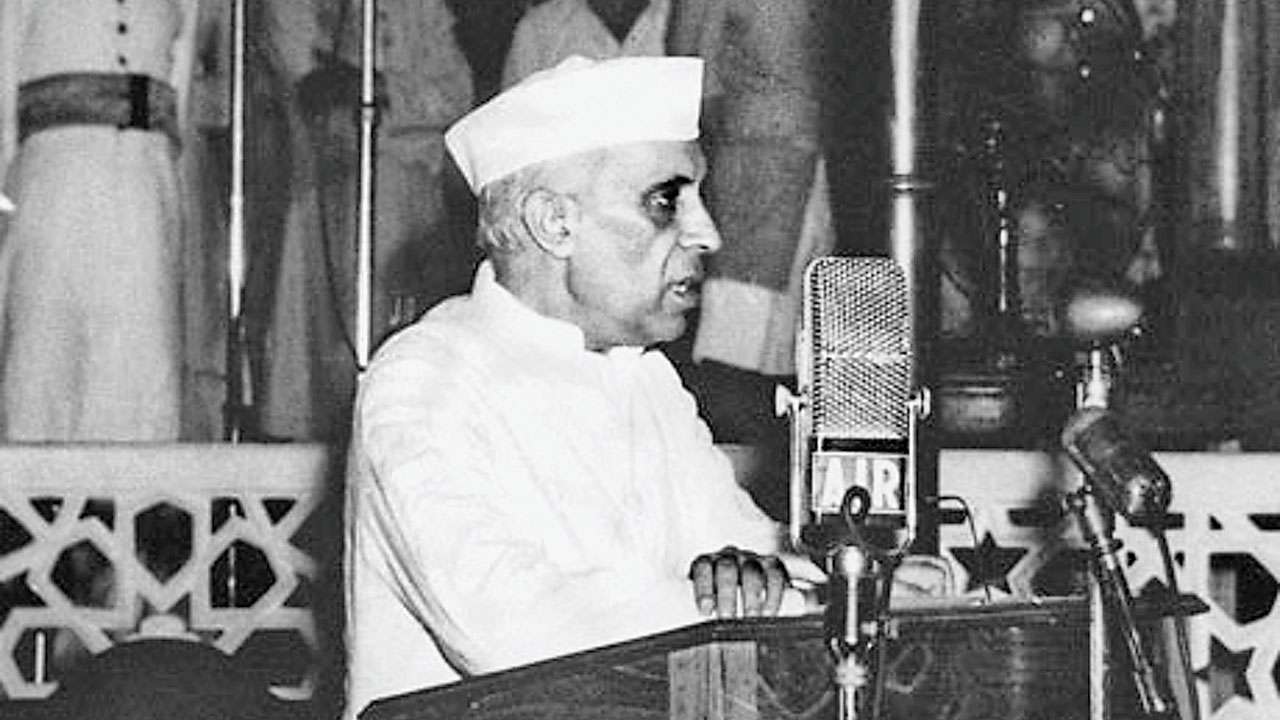

Nehru campaigned for China’s entry in the UN, and for making it a member of the UN Security Council (UNSC) at the expense of India’s chance of becoming a member of that apex body.

Even though never requested by China, India voluntarily and vigorously advocated Peoples Republic of China (PRC) for the permanent membership of the UNSC in lieu of Taiwan, lobbying with all nations for the UN membership and UNSC permanent seat - not for itself, but for China.

Both the US and the USSR were willing to accommodate India as a permanent member of the UNSC in 1955, in lieu of Taiwan, or as a sixth member, after amending the UN charter.

Nehru wanted the seat to be given to China, as he did not want them to be marginalised, a gesture reciprocated by China in kind seven years later in 1962.

That the lesson was completely lost on Nehru is evident from the fact that Nehru’s sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit — the first woman president of the United Nations General Assembly — advocated China’s case even in 1963.

Shashi Tharoor in his book ‘Nehru: The Invention of India’ recalls that when the US offered support for an “Indian Monroe Doctrine” in southern Asia in 1953, Nehru turned John Foster Dulles down with scorn.

“Indian diplomats who have seen the files swear that at about the same time Jawaharlal also declined a US offer to take the permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, then held, with scant credibility, by Taiwan, urging that it be offered to Beijing instead”.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in his speech in Parliament in August 1959, recalled how the Chinese occupation of Tibet in October 1950 notwithstanding, India had decided to raise the question of China’s admission into the United Nations in September 1959 at Nehru’s bidding.

On November 18, 1950, the representative of El Salvador moved the United Nations formally and asked the General Assembly to create a special committee to ‘study’ what measures should be adopted by the United Nations General Assembly to shield Tibet against ‘unprovoked’ Chinese aggression.

But when the Steering Committee of the United Nations met, the Indian representative asked the committee to drop the whole matter. When Vajpayee had moved a resolution in Parliament that simultaneously India should also raise the Tibetan issue in the United Nations, Nehru was unresponsive.

KM Panikkar, the Indian Ambassador in Beijing, stated that to protest the Chinese invasion of Tibet would be an act of interference vis a vis India’s efforts on behalf of China in the UN and destroy PRC’s prospects of entry into the UN.

Vallabhbhai Patel did try to draw the attention of Nehru to the threat expansionist China, warning against pursuing its entry into the UN, without quid-pro-quo, but Nehru seemed to be living in his own world, so far as China was concerned.

Patel advise came “in view of the rebuff which China has given us and the method which it has followed in dealing with Tibet”.

“There would probably be a threat in the UNO virtually to outlaw China, in view of its active participation in the Korean War”, Patel warned in his letter to Nehru, “We must determine our attitude on this question also.”

Nehru went ahead with his bull-headed stubbornness, his miscalculations driven by his inexplicably adamant and unreasonable approach, which ended up creating and complicating India-China border problem and allowed it to drift into an unfortunate war.

He bungled Kashmir in 1947-48 by refusing the military advice of its generals to clear the state of invaders, and internationalised the issue by sending it to the UN.

The Panchsheel in 1954 and the Indus Water Treaty in 1960, with zero reciprocity, amounted to massive giveaways.

After signing the Panchsheel agreement with China in 1954 and helping Chou Enlai to emerge into the limelight in Bandung in 1955, Nehru’s starry-eyed phase of “Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai” blissfully glossed over the real divergence of interests between the two countries at that time.

India exploded a bomb in 1974, but instead of declaring weapons status, it declared its intent to stay non-nuclear and left itself vulnerable to external pressures to disarm.

Nehru’s idealistic shenanigans were fatal, to say the least. Patel was strongly against the reference of Kashmir to the UN and preferred ‘timely action’ on the ground.

Because of this reference, the issue no longer remained an internal affair, but snowballed into an international issue in the UNSC, enabling Pakistan to rake it up every now and then.

If the grand old party is willing to own up the role of Indian National Congress in liberating India from the British rule all to itself, it must also be willing to accept that many of the pathogens still afflicting India are bequeathed to India by Nehru. Cosying up to China is one of them.

Author is a commentator on geopolitical affairs, development and cultural issues