The earthquake alarm sounded, but then teachers disagreed on where to run to safety - seventy out of 108 pupils died.

The siren that blared out from the tower alongside Okawa Elementary School was strident and unmistakable.

Minutes after the Great East Japan Earthquake had shaken this community so violently that children and teachers fell to their knees and shielded themselves from everything that was falling, a far more serious danger was rapidly approaching.

None of the 108 children at the school had experienced an earth tremor of magnitude 9 before but, as all Japanese pupils are trained to do, they responded in accordance with the emergency plan and quickly assembled in the playground. By this time, the massive wave was roaring into the bay at the mouth of the Kitakami River and beginning its sweep inland.

A heated disagreement reportedly delayed their next steps, with a senior teacher insisting that they should make for higher ground close to the bridge over the river, while another teacher argued the children should climb the wooded hill that rises steeply behind the school.

The delay proved fatal. With the tsunami ripping through the 110 homes that lay between the school and the coast and broaching the dyke, the children belatedly made for the bridge but were engulfed.

Seventy pupils were killed and, one year later, another four are still missing. Ten teachers were among the dead and another has still not been found.

On the wall in Masako Karino's room are photographs of her son, Tatsuya - a smiling 11 year-old who was swept away by the tsunami that swallowed the school, and his eight-year-old sister, Misaki.

Tatsuya liked to draw, and his framed pictures of fantasy deities and sunflowers are propped against the wall. He had a globe and knew the different television stations in countries around the world. When he grew up, A heated disagreement reportedly delayed their next steps, with a senior teacher insisting that they should make for higher ground close to the bridge over the river, while another teacher argued the children should climb the wooded hill that rises steeply behind the school. wanted to design computer games.

"Misaki was very cheerful and bubbly," Mrs Karino adds in a quiet, controlled voice. "But she was also competitive and she hated to lose at anything. She had a unicycle, but she would never wear trousers - it was always a skirt or a dress, no matter the weather. I kept telling her that she would fall off and scrape her knees, but she never listened to me, so she kept falling and cutting her knees."

On the afternoon of March 11, Mrs Karino had been frantically trying to get home after the earthquake struck but the roads were blocked. Her husband attempted to find a way along the high embankment that protected their community from the river, but the tsunami had already overcome it and destroyed dozens of homes.

Soon it was dark and they had no choice but to wait for daybreak. After a sleepless night, Mr Karino climbed through the pine forests that separate their valley from the school. "He saw water all around the school," Mrs Karino says. "He knew straight away there was little chance they could have survived."

Of all the individual tragedies that befell north-east Japan one year ago, few are more poignant than that which occurred here.

The school is the only building that still stands in a scoured landscape. Homes, shops, hospitals and the local community centre have all been eradicated. A year on, trucks are hauling away the last few piles of collected debris.

The salty smell of the sea is mixed with the stench of the black mud that remains coated across the village. In the elementary school, not a window remains intact but the concrete shell stands, with blackboards still in place and a mural of children in different national costumes. Two wooden desks salvaged from the debris are stacked on top of one another in an empty classroom. Plastic sheeting flaps in the bitter wind.

The hill that stands behind the school and offered the children sanctuary is unmarked.

As soon as they were able, parents started looking for their children.

One day, after lifting lumps of shattered wood and twisted metal in the remains of the village, Mr Karino discovered the security alarm that all Japanese children are issued with that had belonged to his son.

"He picked it up and it started buzzing," Mrs Karino said. "He couldn't turn it off so he just held it between his hands and brought it all the way home. When he got here, it stopped."

Tatsuya's body was found on March 22. Without warning, his alarm sounded again in the night of April 1. The following day, Misaki's body was discovered. The alarm has not gone off since.

"It has been nearly a year now, but it seems as if it all happened just yesterday," says Mrs Karino. "We have gone through all the rites for when a person dies and I am aware that they are no longer with us, but I still get the feeling that they are here. Because we live a long way from the river, we did not lose our home or any of our belongings, so the only thing that is missing is the children and hearing them come home in the afternoon."

Mrs Karino has returned to her job, for a construction company in Ishinomaki, because it helps take her mind off things, she said.

Her husband has arguably taken their loss worse and keeps saying that he wished he had spent more time with the family and not at work.

Mrs Karino said the local authorities had offered counselling - albeit four months after the disaster - but she does not have the strength to be angry about all that has happened any more.

Not all the bereaved parents feel the same way, however.

Naomi Hiratsuka was locked in an animated discussion with a town official in a hard hat just yards from the school where her 12-year-old daughter, Koharu, was also among those killed. For the past 10 days, a one-mile stretch of a tributary of the river had been dammed to enable the first search of the area, but heavy rain and snow had filled a pool above the dam and authorities said they had no choice but to release the water.

"We have pleaded with them not to, to give us a few more days, but they say it's not possible," says Mrs Hiratsuka, 38.

"It's the same old story; they have not done enough for us," she said.

"Everything that they have done is too little, too late."

It took a long time for the searchers to discover Koharu's body and she was only found, on Aug 8, about three miles away in the neighbouring Naburi Bay. In the meantime, Mrs Hiratsuka completed a course in operating heavy machinery and used a rented digger to help with the search.

Even after Koharu was found, she continues the search for the other missing children.

"In the morning, I send my other two children to school and then I come here and dig all day," she says. "I'll take a break for lunch and then start again. When it gets dark, I'll go home and make dinner for the family. That is my life now," she says with a shrug.

Methodically, Mrs Hiratsuka's digger rakes over a stretch of ground that used to be someone's garden.

Nothing remains standing between the river and the base of the pine-clad hill to the south.

One year on, the death toll from the worst natural disaster to befall Japan in living memory stands at 15,846, with a further 3,320 still listed as missing.

In towns such as Ishinomaki, Minami Sanriku and Ofunato, heavy machinery has cleared away most of the debris and left order of a sort. The remnants of these communities are being sorted - with typical Japanese thoroughness - into mounds of plastic, piles of wood that has come from buildings, lengths of lumber and metals.

Other victims of the disaster - such as the cargo ship the Kyoutokumaru, which is propped upright on the foundations of a home in Kessenuma, with a burnt-out car beneath its keel - will take longer to remove. All along the coast, diggers and trucks are in constant motion, taking away the physical reminders of a tragedy.

Next weekend, on March 11, a priest will come to the Karino family home to perform solemn rites and the relatives will gather to mark an unwanted anniversary. Mrs Karino says: "I understand what has happened and I know that they are not coming back, so there are times when the lows are very low and I don't think that I am coping very well at all.

"But we have to go on," she added. "That is why my husband and I have decided to have another child."

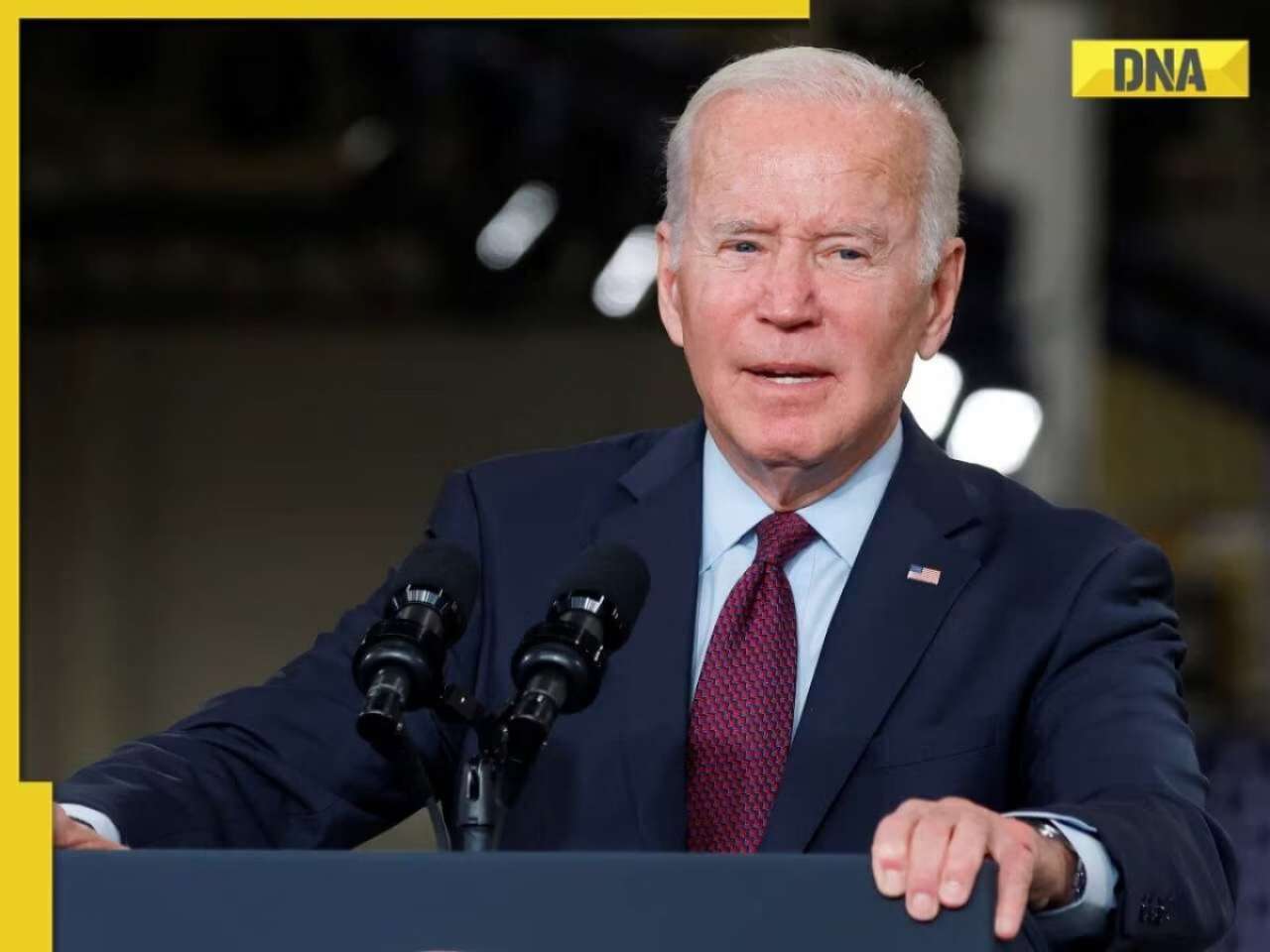

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)