Mining for rare earths, used in green products, is causing great harm to ecology and environment.

Some of the greenest technologies of the age, from electric cars to efficient light bulbs to large wind turbines, are made possible by an unusual group of elements called rare earths. The world’s dependence on these substances is rising fast.

Just one problem: These elements come almost entirely from China, from some of the most environmentally damaging mines in the country, in an industry dominated by criminal gangs.

Western capitals have suddenly grown worried over China’s near monopoly, which gives it a potential stranglehold on technologies of the future. In Washington, Congress is fretting about the U.S. military’s dependence on Chinese rare earths, and has just ordered a study of potential alternatives.

Here in Guyun Village, a small community in southeastern China fringed by lush bamboo groves and banana trees, the environmental damage can be seen in the red-brown scars of barren clay that run down narrow valleys and the dead lands below, where emerald rice fields once grew.

Miners scrape off the topsoil and shovel golden-flecked clay into dirt pits, using acids to extract the rare earths. The acids ultimately wash into streams and rivers, destroying rice paddies and fish farms and tainting water supplies.

On a recent rainy afternoon, Zeng Guohui, a 41-year-old laborer, walked to an abandoned mine where he used to shovel ore, and pointed out still-barren expanses of dirt and mud. The mine exhausted the local deposit of heavy rare earths in three years, but a decade after the mine closed, no one has tried to revive the downstream rice fields.

Small mines producing heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium still operate on nearby hills.

“There are constant protests because it damages the farmland — people are always demanding compensation,” Zeng said.

“In many places, the mining is abused,” said Wang Caifeng, the top rare-earths industry regulator at the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology in China. “This has caused great harm to the ecology and environment.”

There are 17 rare-earth elements — some of which, despite the name, are not particularly rare — but two heavy rare earths, dysprosium and terbium, are in especially short supply, mainly because they have emerged as crucial ingredients of green energy products. Tiny quantities of dysprosium can make magnets in electric motors lighter by 90 percent, while terbium can help cut the electricity usage of lights by 80 percent. Dysprosium prices have climbed nearly sevenfold since 2003, to $53 a pound. Terbium prices quadrupled from 2003 to 2008, peaking at $407 a pound, before slumping in the global economic crisis to $205 a pound.

China mines more than 99 percent of the world’s dysprosium and terbium. Most of China’s production comes from about 200 mines here in northern Guangdong and in neighboring Jiangxi province.

China is also the world’s dominant producer of lighter rare earth elements, valuable to a wide range of industries. But these are in less short supply, and the mining more regulated.

Half the heavy rare earth mines have licenses and the other half are illegal, industry executives said. But even the legal mines, like the one where Zeng worked, often pose environmental hazards.

A close-knit group of mainland Chinese gangs with a capacity for murder dominates much of the mining and has ties to local officials, said Stephen G. Vickers, the former head of criminal intelligence for the Hong Kong police who is now the chief executive of International Risk, a global security company.

Zeng defended the industry, saying that he had cousins who owned rare-earth mines and were legitimate businessmen who paid compensation to farmers.

Western users of heavy rare earths say that they have no way of figuring out what proportion of the minerals they buy from China comes from responsibly operated mines. Licensed and illegal mines alike sell to itinerant traders. They buy the valuable material with sacks of cash, then sell it to processing centers in and around Guangzhou that separate the rare earths from each other.

Companies that buy these rare earths, including a few in Japan and the West, turn them into refined metal powders.

“I don’t know if part of that feed, internal in China, came from an illegal mine and went in a legal separator,” said David Kennedy, president, Great Western Technologies, which imports Chinese rare earths and turns them into powders that are sold worldwide.

Smuggling is another issue. Kennedy said that he bought only rare earths covered by Chinese export licenses. But up to half of China’s exports of heavy rare earths leave the country illegally, other industry executives said.

![submenu-img]() Rakesh Jhunjhunwala’s wife sold 734000 shares of this Tata stock, reduced stake in…

Rakesh Jhunjhunwala’s wife sold 734000 shares of this Tata stock, reduced stake in…![submenu-img]() West Bengal: Ram Navami procession in Murshidabad disrupted by explosion, stone-pelting, BJP reacts

West Bengal: Ram Navami procession in Murshidabad disrupted by explosion, stone-pelting, BJP reacts![submenu-img]() 'We certainly support...': US on Elon Musk's remarks on India's permanent UNSC seat

'We certainly support...': US on Elon Musk's remarks on India's permanent UNSC seat![submenu-img]() Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’

Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore

Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’

Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore

Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore![submenu-img]() India's first female villain was called Pak spy; married at 14, became mother at 16, left family to run away with star

India's first female villain was called Pak spy; married at 14, became mother at 16, left family to run away with star![submenu-img]() Dibakar Banerjee says people didn’t care when Sushant Singh Rajput died, only wanted ‘spicy gossip’: ‘Everyone was…'

Dibakar Banerjee says people didn’t care when Sushant Singh Rajput died, only wanted ‘spicy gossip’: ‘Everyone was…'![submenu-img]() Most watched Indian film sold 25 crore tickets, was still called flop; not Baahubali, Mughal-e-Azam, Dangal, Jawan, RRR

Most watched Indian film sold 25 crore tickets, was still called flop; not Baahubali, Mughal-e-Azam, Dangal, Jawan, RRR![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: DC thrash GT by 6 wickets as bowlers dominate in Ahmedabad

IPL 2024: DC thrash GT by 6 wickets as bowlers dominate in Ahmedabad![submenu-img]() MI vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

MI vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() MI vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Punjab Kings

MI vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Punjab Kings ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Big boost for LSG as star pacer rejoins team, check details

IPL 2024: Big boost for LSG as star pacer rejoins team, check details![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR

IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Deserts around Saudi Arabia's Mecca and Medina are turning green due to…

Watch viral video: Deserts around Saudi Arabia's Mecca and Medina are turning green due to…![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

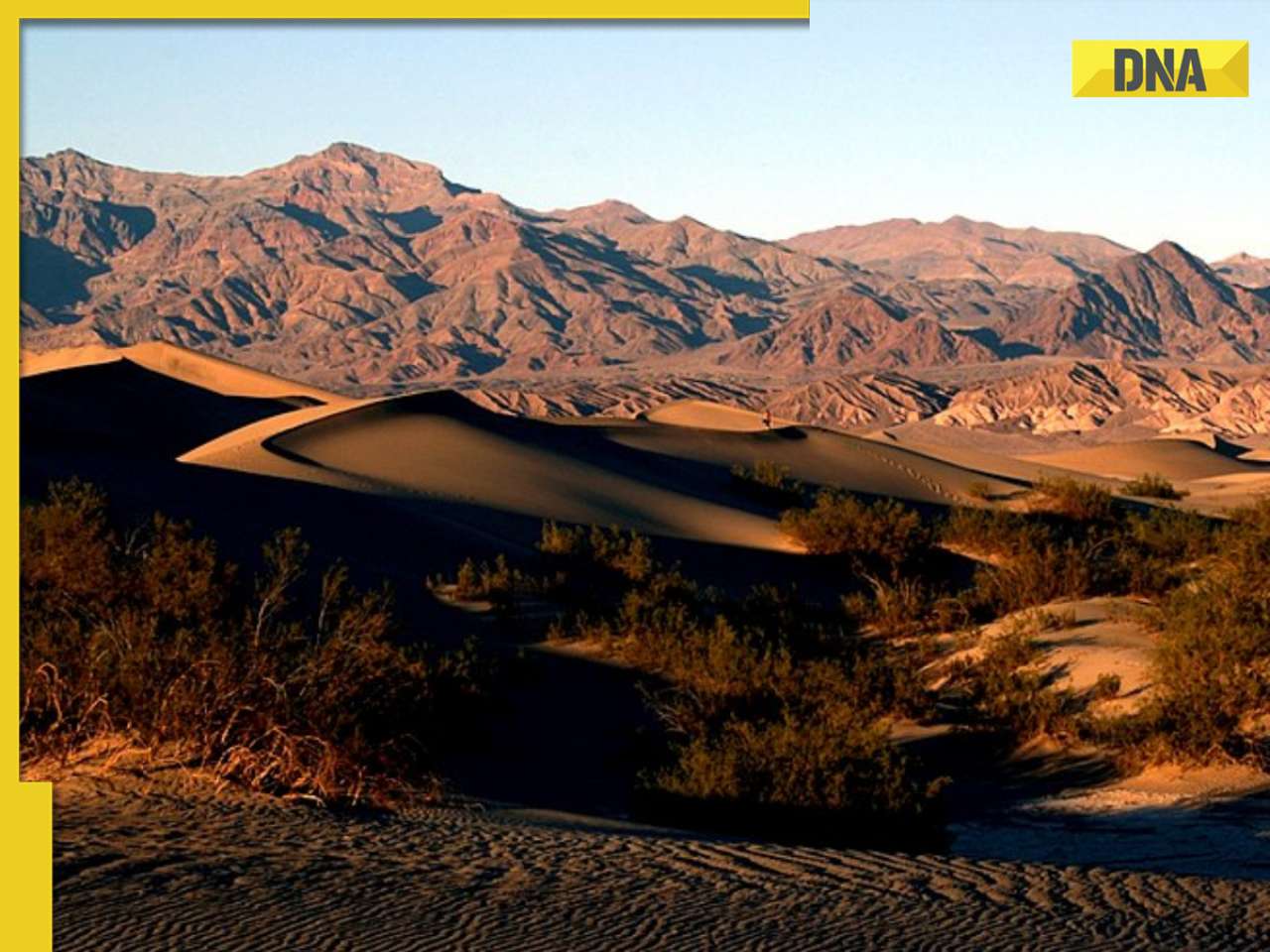

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here

Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

)

)

)

)

)

)