Prime Minister David Cameron announced on September 7 the resettlement scheme would be expanded, responding to public clamour for his government to help those fleeing civil war in Syria.

Arrested and tortured back home, Khalil, one of the first Syrian refugees to be resettled in Britain, is finding it harder to adapt to a new life in chilly northern England than his children.

In the vanguard of Britain's resettlement scheme for Syrian refugees, Khalil is grateful to have avoided a perilous Mediterranean sea crossing and overland trek through unwelcoming nations in southeastern Europe. But challenges lie ahead.

"I find learning a new language at my age a little bit difficult," said the 40-year-old former shop owner through an Arabic translator. "My kids are really amazing, they are learning English very quickly, I am learning from them."

Because of the horrific abuse he had suffered, Khalil's family was put on a United Nations list from which the British government takes Syrians deemed most in need. About 200 have arrived so far, half of them to Bradford, a former industrial city with a long history of immigration.

"In nine or twelve months (refugee children) are speaking English fluently with little Yorkshire accents, which is lovely to see," said Gudrun Carlisle of Horton Housing Association, which helps settle the Syrian families in the city.

Prime Minister David Cameron announced on September 7 the resettlement scheme would be expanded, responding to public clamour for his government to help those fleeing civil war in Syria, with 20,000 refugees set to come over five years.

FAMILY FLED

Khalil owned a mobile phone shop in Zabadani near Syria's border with Lebanon when, after the war began, he was arrested by government security forces four separate times, and tortured. He suffers from severe pain in his right hip as a result.

The family fled to Lebanon where they spent two years living in a tiny ramshackle garage. His family was hassled by officials to pay for needless documents, and suffered discrimination as Sunni Muslims in a predominantly Shi'ite area.

"When I travelled to Lebanon I had no work," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. "There was no way to heat that place with my kids, the walls were made of mud." Khalil, who gave only his first name for fear of reprisals against his family in Syria, was eventually identified by the U.N. refugee agency UNHCR as particularly vulnerable. He was flown to Bradford with his pregnant wife and children in June, reluctantly leaving his brother and elderly parents behind.

YORKSHIRE ACCENTS

Syria's civil war, which erupted in 2011, has killed about 250,000 people, uprooting some 7.6 million within Syria and creating 4 million refugees, most of them living in camps in nearby Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey.

At least 182,000 Syrians have crossed the Mediterranean to Europe so far in 2015, almost 40% of the total of refugees and migrants making the sea crossing. Of the small number of Syrians resettled in Britain so far, half are in Bradford. The city has a proud history of welcoming refugees, with Jews, eastern Europeans and Pakistanis arriving in the 20th century, said David Green, leader of the council.

Officials meet refugees at the airport and slowly induct them into British life, providing translators as well as helpers to sort out schools, healthcare and housing. Khalil, wearing a thick black jacket, sits in an English lesson provided for the refugees.

"Can you pass the scissors please?" he and his classmates say in turn, some already speaking with a hint of their teacher's Yorkshire accent. Though children learn quickly, adult refugees are often slow to pick up the language, limiting their employment options even though many are highly qualified, said Gudrun Carlisle. "We have a doctor here, we have a woman who started her own business."

PHONING HOME

Khalil currently lives off government benefits, but wants to work when he has a better grasp of the language. "I used to have a shop," he said. "I don't think I'd be able to do that here, but I plan to work in restaurants or find another kind of job that suits me."

He likes taking his children to see the parks and old buildings in Bradford, but is apprehensive about his first British winter. But his main worries are about his family back home. His parents are still in Lebanon, his mother very ill, while his cousin's family are stuck in the town of Madaya near Zabadani, trapped in fighting between government forces and rebels.

"We try to contact them every day, but the communications are cut all the time. Whenever we do, we hear the bombing and the shooting. "My kids all the time ask me: What about our grandma and grandpa? Are we going to see them again?'" Khalil does not know, but is looking for positives where he can find them. "I am settled now, I feel safe, people are welcoming," he said. "I live in dignity here."

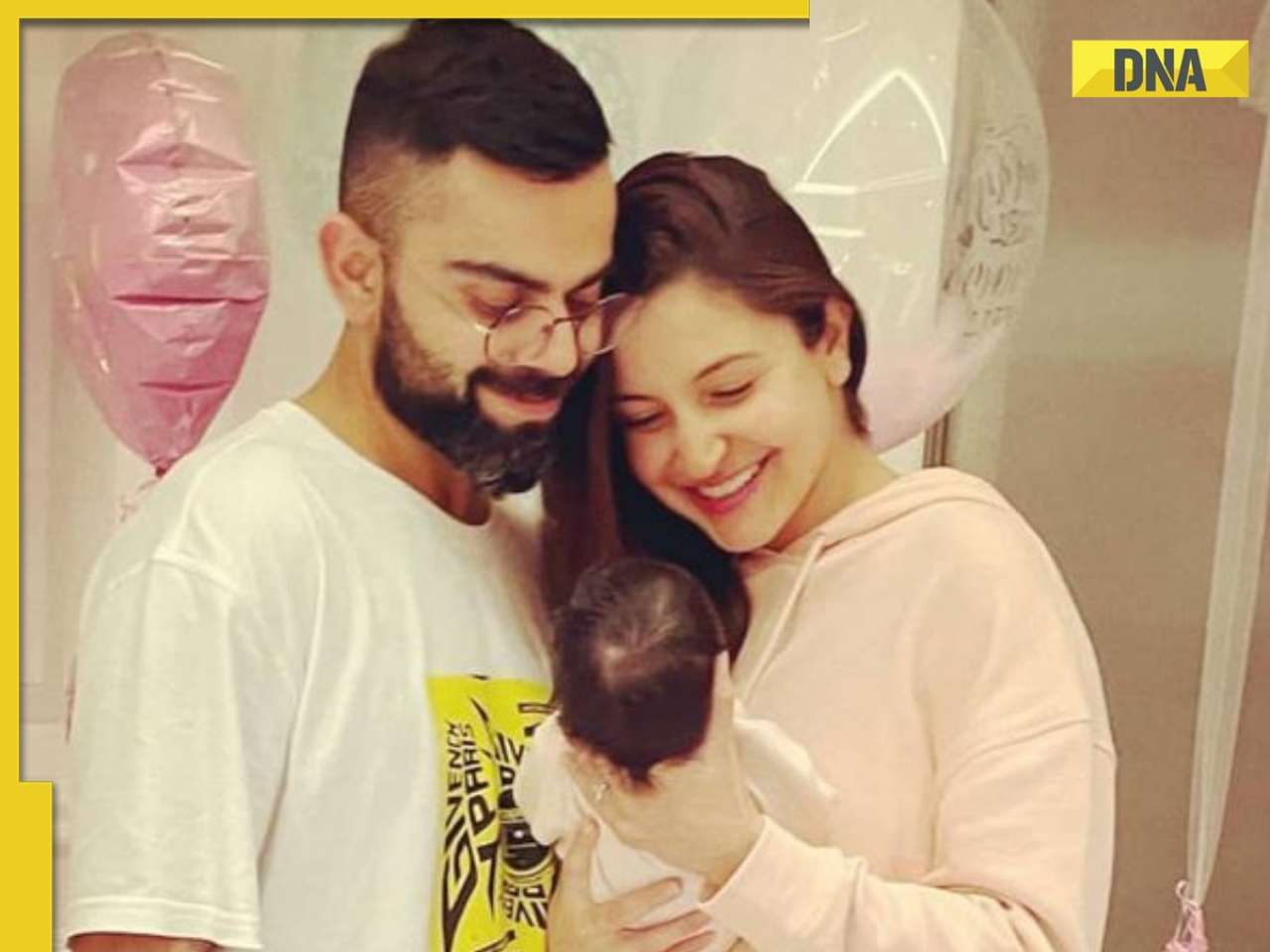

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

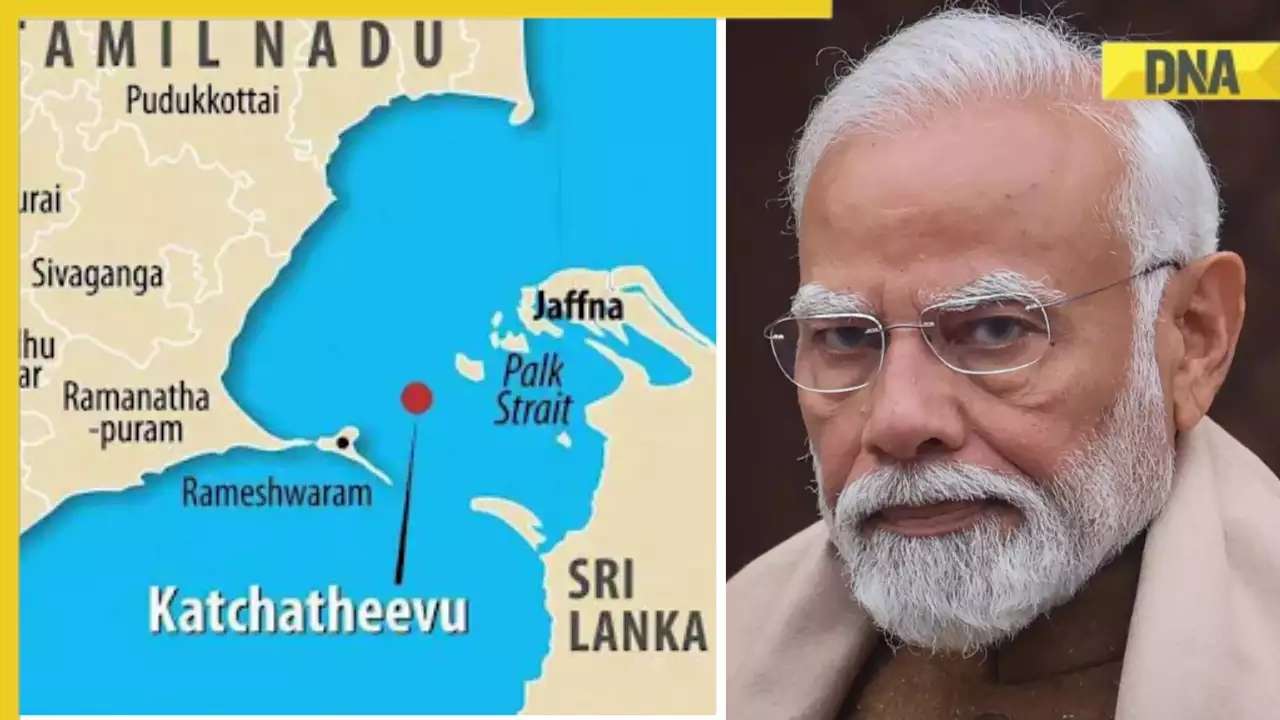

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)