Madina, a university student in the Central Asian former Soviet republic of Tajikistan, was attending a journalism seminar this summer when a classmate asked the lecturer a question.

Madina, a university student in the Central Asian former Soviet republic of Tajikistan, was attending a journalism seminar this summer when a classmate asked the lecturer a question.

"If I were to write an article about the business interests of the president's family, would I encounter any problems?"

The lecturer, a government official, praised Imomali Rakhmon, Tajikistan's long-serving president, but sidestepped the issue.

The student was later hauled into the rector's office to explain why he had posed such an undesirable question.

Tajikistan, a poor country of 7.5 million people which borders Afghanistan, is still struggling to find its way after a civil war in the 1990s that killed tens of thousands but failed to end inter-clan infighting.

With a presidential election just a year away, it appears to be clamping down on dissent. Universities and colleges appear to be the latest to feel the heat. Rakhmon, a 60-year-old former cotton farm boss, has ruled the country - a major transit route for Afghan drugs to Europe and Russia - since 1992 and the election offers him a chance to extend his two-decade rule for a further seven years.

His first five years in power were spent fighting a civil war against an opposition alliance backed by Islamist militants.

A Moscow-brokered peace deal ended that conflict in 1997 and guaranteed some government jobs for the opposition.

But recent military offensives in the mountainous east suggest Rakhmon's patience with these former warlords is wearing thin. As the government has turned its attention to damping down dissent in the education sector it has focused on extracurricular seminars organised by non-governmental organisations and human rights bodies, sometimes with the support of Western embassies.

A new directive from the Education Ministry, a copy of which has been obtained by Reuters, has made it compulsory for organisers to receive prior government permission.

A handful of events have already been delayed. Rakhmatillo Zoiirov, leader of the opposition Social-Democratic Party of Tajikistan, calls such measures an example of "the totalitarian mindset" of the authorities.

"It stems from their fears that political themes will be floated during conferences and seminars in the run-up to the presidential elections, and that foreigners might say something unpleasant about the president and the government," he said.

Having previously adopted a relatively liberal stance on media freedom, Tajikistan has also sporadically blocked social networking sites in recent months, including Facebook, and created a volunteer body to monitor Internet use and reprimand critics.

Such measures are reminiscent of the stringent controls in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, where authoritarian rulers are wary of the role social media played in Russia's mass protests and revolutions in the Arab world.

An 18-year-old student in Dushanbe, Tajikistan's capital, told Reuters in July that he had been detained overnight and lectured repeatedly by secret police after posting criticism of the president on his Facebook page.

Madina, the first student, said she believed officials were afraid of the ideas often discussed during foreign-run seminars.

The event she attended was backed by Amnesty International. "This is where people speak out," she said, "and our leaders would prefer that we sit down and keep quiet".

Rumbles of discontent

Tajikistan has more than 118,000 students in full-time higher education, about 70 percent more than when the country gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. But around 1 million of its citizens, more than a tenth of its population, work abroad in menial jobs and send home cash that accounts for more than 40% of the country's gross domestic product.

Most are young men of working age, the key demographic for the kind of protests seen in Russia. Dissent among the older generation, which recalls the 1992-1997 civil war, is rare. Opposition politicians and academics say the authorities are concerned grinding poverty in a country where some rural areas are without electricity for much of the year could give rise to discontent ahead of the election, which is scheduled for November 2013.

"Children, especially in rural areas, are cold, hungry, unhealthy and experience constant humiliation from their parents and from the state and society in general," said Kamoludin Abdullaev, a freelance historian. He said hundreds of students were made to stand and welcome Rakhmon when the president opened a road tunnel last month, in a ceremony reminiscent of those organised for Turkmen President Kurbanguly Berdymukhamedov at civic functions.

However, the government says its doors remain open to NGO-sponsored events. Deputy Education Minister Farkhod Rakhimov, signatory to the directive, said Tajikistan would continue to permit foreign-run seminars, provided they met government criteria.

"International organisations should inform the ministry in advance of planned conferences and seminars and supply a list of students whom they plan to invite," he told Reuters.

"They should explain (to the ministry) the value of such an event to the students themselves." But a Western diplomat said he knew of at least two seminars - one on human rights, the other on local government issues - that had been postponed since the new directive was introduced.

"When we talk about human rights, (and) torture in prison, the students are sometimes even more critical than their trainers," said the diplomat, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

"They tell participants about instances of torture that they have heard about from their relatives or neighbours. This is a bone of contention for the officials who often take part."

Brain drain

Critics of Tajikistan's education system say universities do little to encourage diversity or freedom of thought. Dress codes are strictly enforced - no jeans or T-shirts - and some students say qualifications are not always awarded on merit.

"Of 23 students in our group, only 15 come to class," said another student in Dushanbe, who declined to be identified for fear of disciplinary measures.

"We have never seen the others, but their absence is never questioned because they are the children of government officials or simply have the money to buy their way through," he said. Abdumalik Kadirov, director of the Tajik representative office of the London-based Institute for War and Peace Reporting, said the overall standard of education would decline without the variety offered by foreign teaching.

"Our students will be even further removed from the latest developments in science and technology and new trends in global education," he said. Abdullaev, a Fulbright scholar originally from Tajikistan who teaches Central Asian history in the United States, said restrictions could also drive the brightest young minds abroad.

"Our young people are patient and hard-working. They are brought up to respect their elders and fear power," he said. "They don't wish to repeat the fate of their parents, who fear a return to civil war. They are not rushing to man the barricades. But neither do they wish to put up with a lack of freedom."

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

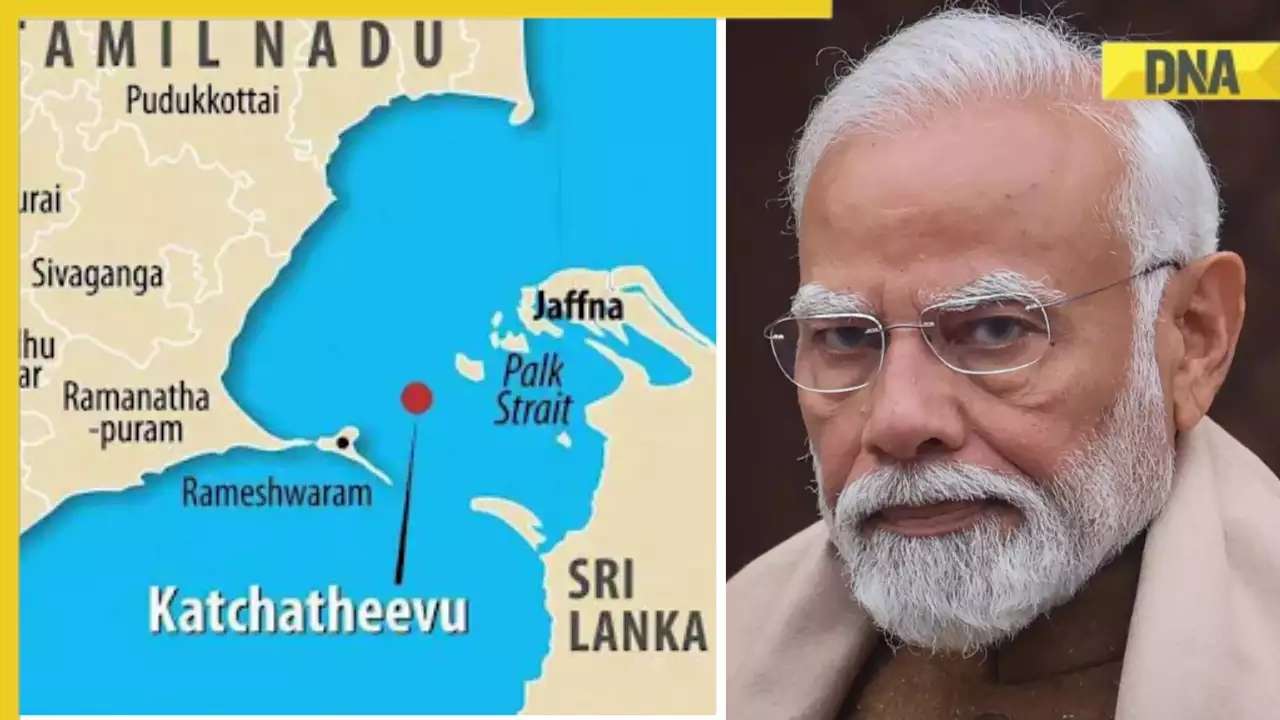

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)