As news of the Great Barrier Reef's (GBR) death spirals into various debates, Dr Deepak Apte, Director, Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), who's been studying reefs for the past 30 years, debunks myths and tells us about the challenges.

Some feel Outsider Online's obituary was a need as no one's listening, your take?

The current debate is nothing but sensationalisation of an issue. Such articles can have an adverse effect. If we declare the reef is dead, policy makers will be glad to have nothing to bother about and will open it up for cement mining. Rather than giving them such opportunity by relegating the GBR to the graveyard, we should use this event to build political consensus for strategic surgical interventions to help reefs.

Reports say bleaching has impacted 93% of the GBR. How could we have prevented it?

The 2016 coral bleaching was global phenomenon, which not only affected the Great Barrier Reef, but also Maldives, the Coral Triangle, Lakshadweep and the Gulf of Mannar. But there's nothing we could have done; it wasn't human induced. You see, bleaching is a natural phenomenon that will continue to happen. Such catastrophic events are required to drive evolutionary processes so that over-mature ecosystems whose productivity has reduced with time, give way to fresh ecosystems. In the next 15 – 20 years GBR may get restored into new hard coral or soft coral.

It becomes a major concern only in the human dimension because livelihood of millions depends on the ecosystem services provided by these reefs. Thus in the 'human' context, yes, the impact is major and global, but in 'ecosystem' and 'nature' contexts, there's nothing like impact—but merely a shift to a new ecosystem. It's our ignorance about ecosystems that leads to extreme activist views.

You say it wasn't human induced, but what about the impact of global warming?

Climate change has been happening over a period of time, only the pace has increased significantly over the last 100 years, due to industrialisation. But ocean warming (which causes bleaching) has occurred for aeons.

Yes, if bleaching results from acidification—that results from carbon emissions entering sea water—you can blame global warming. But, that would have a local or at the most regional impact. What we saw this year was due to El Nino warming. We are not capable of causing the whole world's ocean temperature to rise by 1 to 3 degree! Only the sun has that power. Pinning everything on global warming doesn't make sense.

Well, then what are scientists fighting for? Is there a way to revive the reefs?

We can't avoid bleaching events, but can certainly assist reef recovery. It would require some hard decisions and strong political will. What's alive of GBR is capable of reviving large tracts of reef in over a decade or so. We've seen such success with Lakshadweep, which was 80% dead to 50% alive post the 1998 bleaching. The strategy should be: stop tourism for at least five years of natural recovery, and adopt new technology. Dead reefs will lead to a population explosion of herbivorous fish that feed on the excessive growth of algae—the cleaning creates the perfect environment for coral larvae to settle and form new reefs. Hence, these fishes mustn't be harvested. Australian economy depends on GBR, so politicians may find banning impossible, but if not done, GBR will only deteriorate and leave nothing for tourists anyway.

What about Indian reefs, what's their current status?

Vulnerability of reefs varies from place to place and no single parameter defines it. But Indian reefs though smaller than GBR, suffer far more anthropogenic stress. Thus, needless to say, Indian reefs are hugely degraded, barring few (30 - 40) in isolated places like Suheli at Lakshadweep, and Barren Island, Narcondam Island, Craggy Island in the Andamans. But this year, Lakshadweep has suffered bleaching too.

Should the recovery approach for Lakshadweep be different?

For natural recovery, we too need a five-year ban on reef fishing. But must give fishermen alternatives - incentivise them for zero bycatch fishing, and pole and line tuna fishery (that doesn't affect reefs) with better prices. Having worked with them for 30 years, I can guarantee that people at Lakshadweep will support it; we must partner with them.

We also need to ban disposal of dredged sand in lagoons and abandon the proposed Sagar Mala tourism expansion plan at Suheli and Cheriyam among our remaining best five reefs; tourism will ring their death knell.

We just need to build political consensus, at this stage recovery for our reefs is possible.

Wouldn't Lakshadweep too benefit from bio rock technology?

Obviously! These reefs are basically aggregation of calcium carbonate by polyps (a kind of animal), which has an enzyme that binds the calcium in water and converts it into calcium carbonate. Bio-rock technology does this through release of low intensity current in water. Thailand, Australia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Indonesia, the world is adopting it, but India. Here, no one is bothered about reefs, forget recovery and we are so closed to new ways. The technology is patented, but our country has the best minds. If the government asks IIT students to take it up as a project, it would just take us a year to establish protocol and within next 10 years you'll see 200 – 300 hectares of restored reefs. It's very low cost technology when compared to the kind of results it produces.

![submenu-img]() First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..

First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..![submenu-img]() Apple iPhone camera module may now be assembled in India, plans to cut…

Apple iPhone camera module may now be assembled in India, plans to cut…![submenu-img]() HOYA Vision Care launches new hi-vision Meiryo coating

HOYA Vision Care launches new hi-vision Meiryo coating![submenu-img]() This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...

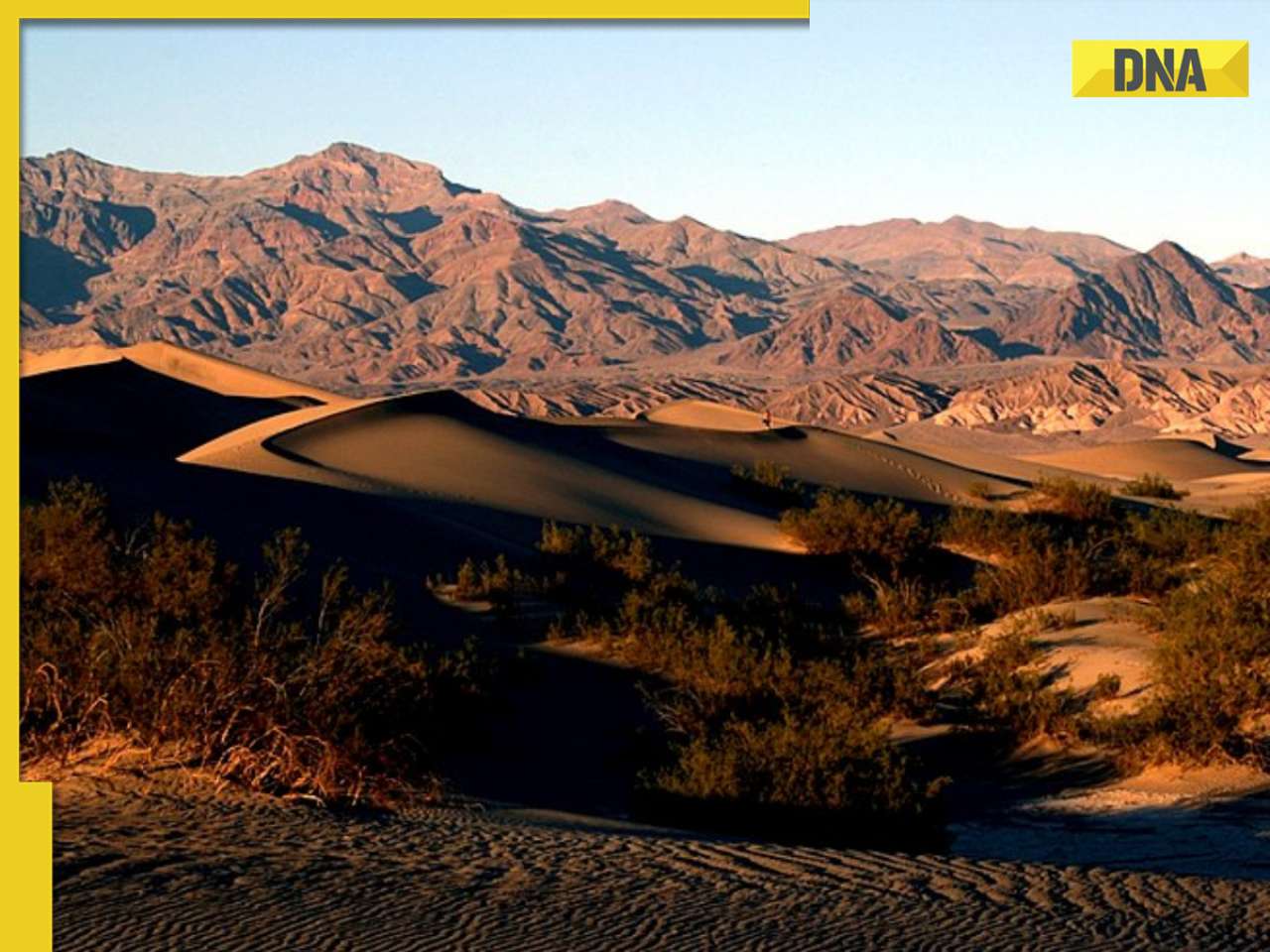

This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

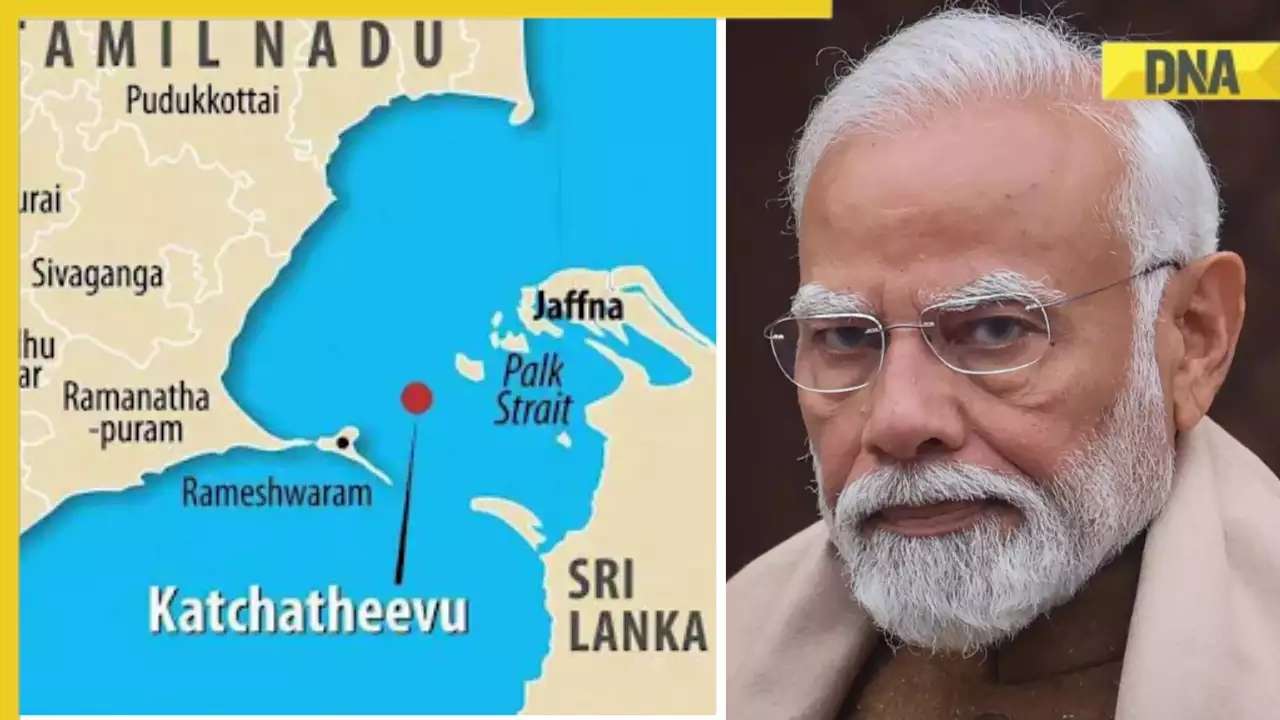

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..

First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..![submenu-img]() This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...

This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...![submenu-img]() Salman Khan to return as host of Bigg Boss OTT 3? Deleted post from production house confuses fans

Salman Khan to return as host of Bigg Boss OTT 3? Deleted post from production house confuses fans![submenu-img]() Manoj Bajpayee talks Silence 2, decodes what makes a character iconic: 'It should be something that...' | Exclusive

Manoj Bajpayee talks Silence 2, decodes what makes a character iconic: 'It should be something that...' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Meet star, once TV's highest-paid actress, who debuted with Aishwarya Rai, fought depression after flops; is now...

Meet star, once TV's highest-paid actress, who debuted with Aishwarya Rai, fought depression after flops; is now... ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR

IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR![submenu-img]() GT vs DC, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs DC, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Delhi Capitals

GT vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'I went to...': Glenn Maxwell reveals why he was left out of RCB vs SRH clash

'I went to...': Glenn Maxwell reveals why he was left out of RCB vs SRH clash![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here

Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

)

)

)

)

)

)

)