The sudden collapse of a power-sharing agreement that ended decades of violence in Northern Ireland has angered a younger generation who feel robbed of their future by the failure of politicians to get over the sectarian prejudices of the past.

The sudden collapse of a power-sharing agreement that ended decades of violence in Northern Ireland has angered a younger generation who feel robbed of their future by the failure of politicians to get over the sectarian prejudices of the past.

After bitter compromises over paramilitaries and policing, the province's cross-community government finally imploded over farmers abusing a green-energy scheme, forcing an election on March 2.

The confrontation has exposed the frustrations of younger people over what they say is a breakdown in trust between Catholic Irish nationalists and pro-British Protestant unionists that has stifled job creation and economic prosperity.

While there is no sign of a return to the violence that killed 3,600 people, the political crisis looks set to paralyse government in the province for months at the same time as Britain's exit from the European Union threatens shockwaves to its economy, constitutional status and border with Ireland.

"People are frustrated because they can't agree on anything. They can't compromise," said Carlos Barr, a 16-year-old student, referring to the older generation of politicians. "If one side says something the other side has to object."

While it is impossible to quantify the impact of sectarian disputes on economic growth, many young people complain they have scared off foreign investment, delayed reforms and deepened a culture of dependency on the state in the two communities.

"CORPORATES PUT OFF"

"People don't come together enough to make it work," said Henry Joseph-Grant, 33, a Northern Ireland-born entrepreneur.

While jobs are disappearing in older industries like farming and manufacturing, Northern Ireland and its politicians lack the entrepreneurial culture to create new ones, he said. "A lot of the big corporates look at Northern Ireland and are put off."

For swathes of the under-30s, the dominant feeling is the violence of the 1970s and '80s still casts a long shadow over political decisions.

"The frustration that young people speak to us about (is that) whilst they are working hard to ... overcome barriers and deal with legacy issues, they feel that this doesn't always happen in mainstream politics," said Chris Quinn, 39, director of the Northern Ireland Youth Forum.

The political crisis came to a head when Democratic Unionist Party First Minister Arlene Foster refused to step aside temporarily to allow an investigation into the green energy scandal and Sinn Fein Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness said he had no option but to resign.

McGuinness, a 66-year-old former Irish Republican Army leader, was replaced by Michelle O'Neill, 40, whose father was jailed during "The Troubles".

McGuinness had a frosty relationship with DUP First Minister Arlene Foster, whose police reservist father narrowly avoided being killed in an IRA shooting when she was a child. The incident, along with a later IRA attack on her school bus, "is part of who I am", Foster recently told an interviewer.

SEARCHING FOR A FUTURE

Two decades after the British army dismantled its garrison in the village of Bessbrook in County Armagh following the Good Friday Agreement that brought peace to the troubled province, 31-year-old Darren Matthews says he struggles to see a future.

"The old people, who are the bitter ones, keep us going round in circles," said Matthews, a construction worker who commutes daily to Dublin and is planning to follow friends in seeking better pay and opportunities outside Ireland.

"If people were not so focused on the (Protestant) orange and (Irish nationalist) green, people would be getting a lot more work done," he said.

Like most of Northern Ireland, Bessbrook was transformed by peace: checkpoints were demolished and helicopter landing pads that supplied military outposts were dug up for farmland.

The nearby Dublin-Belfast road was upgraded, bringing tourists from Ireland to visit Belfast museums and landmarks and pose for photos beside murals in once no-go areas.

But in many areas Northern Ireland badly lags behind its neighbour, with half the tourists per head of population. Dublin has 150 flights a week to the United States. Belfast has none.

Many complain jobs are often of lower quality. Average annual wages are less than in Britain as a whole and Ireland.

There is a steady outflow of school-leavers and graduates seeking their fortune abroad. "Of the guys I grew up with, a lot are scattered around the world" from Australia to Canada, Matthews said. "If the politicians were doing their jobs, more people would stay."

"NO BREAKING ICE"

Few people see the election in March as delivering a breakthrough. "It's that frustration of the inevitability of the election being this big thing to promote change but it definitely won't," Matthews said.

"It's going to be very difficult to have an election of a less sectarian flavour," Jonathan Tonge, Professor of Politics at the University of Liverpool. "I don't really hear the sound of breaking ice."

Early signs are that this election will follow a well-worn pattern, with election posters bearing colours of the Irish or British flag for the two main parties and each side focused on the threat of domination by the other to bring out their base.

Political apathy amongst the younger generation reflects a feeling that older politicians are locked in the past and refuse to engage with issues that they care about. Gay marriage, backed by 84 percent of under 34-year-olds, according to a recent survey, was blocked by the governing Democratic Unionist Party.

Ten of 12 young people questioned by Reuters in a straw poll in Belfast voiced deep frustration with sectarian bickering. They listed funding for mental health, integrated education and reform of power-sharing as issues they wanted dealt with.

Five said they would vote for non-aligned parties, which have made slow progress in recent years, taking 12 of 108 seats in 2016 elections compared to six in 1998.

Voter turnout has fallen consistently from 70 percent in the first Northern Ireland Assembly elections in 1998 to 55 percent last year, with a half of under 22-year-olds voting compared to two-thirds of over 65s.

At Belfast's modern Victoria Square shopping centre, there was little sense the tide would turn any time soon. "It's the same people arguing over the same things, it's the same names," said Maggie McSparron, 27. "They are flogging a dead horse." (Additional reporting by Padraic Halpin; writing by Conor Humphries; editing by Peter Millership)

(This article has not been edited by DNA's editorial team and is auto-generated from an agency feed.)

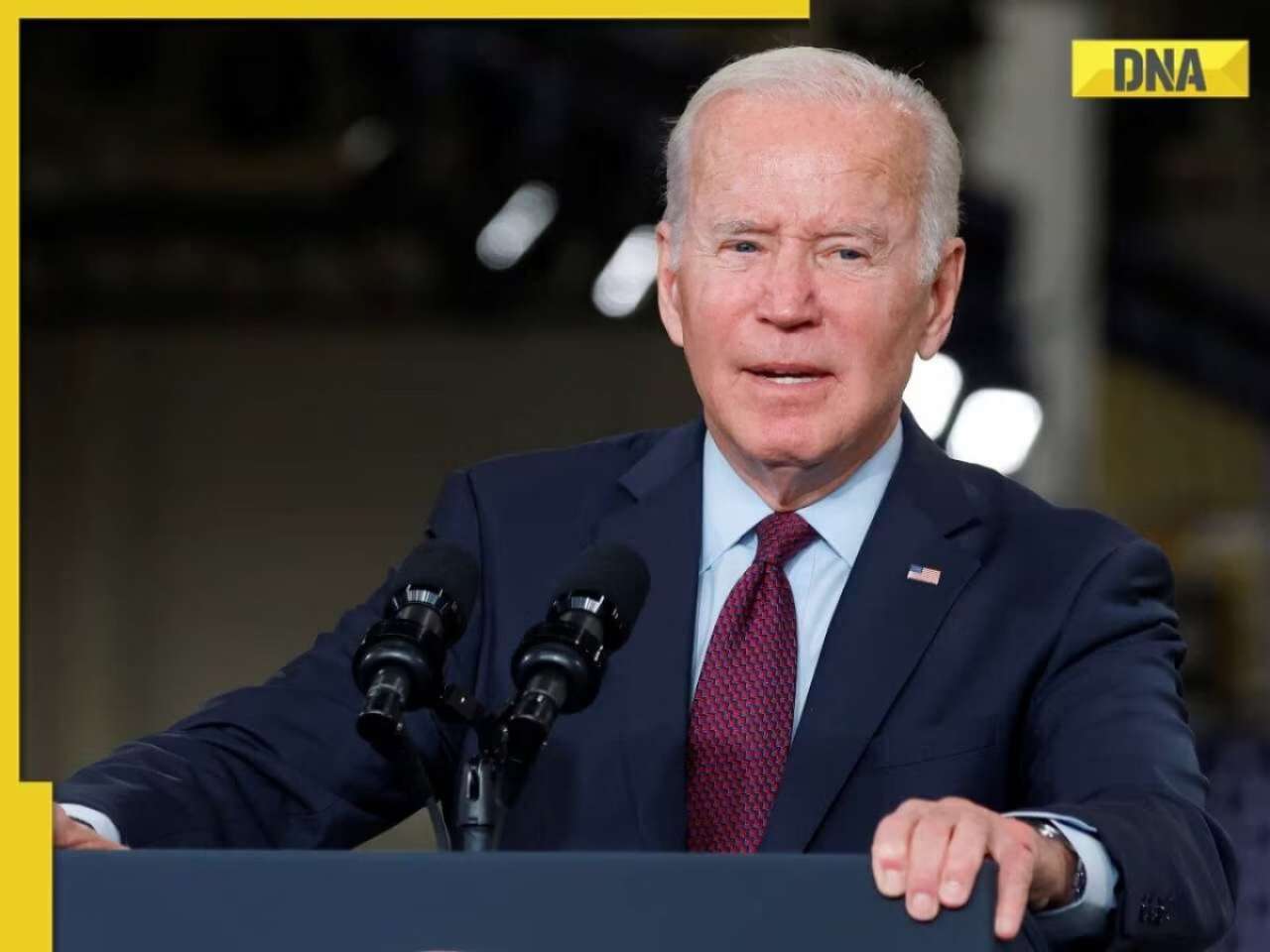

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)