In a five-year struggle with Mexico's most notorious drug cartel, the city of Torreon has suffered a 16-fold increase in murders, fired its police department and lost control of its main prison to the gang.

In a five-year struggle with Mexico's most notorious drug cartel, the city of Torreon has suffered a 16-fold increase in murders, fired its police department and lost control of its main prison to the gang.

The Zetas cartel arrived in Torreon in mid-2007, and this center of manufacturing, mining and farming once seen as a model for progress has become one of Mexico's most dangerous cities.

Massacres at drug rehab clinics, bags of severed heads and gunfights at the soccer stadium have charted the decline of a city that a decade ago stood at the forefront of Mexico's industrial advances after the nation joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Canada.

Once enticing US firms like Caterpillar and John Deere and Japanese auto parts maker Takata to open plants, Torreon has not attracted any other big names since the Zetas swept in. "It's a powder keg," said a former mayor, Guillermo Anaya, who ran the city from 2003 to 2005 and is now a federal lawmaker.

Many people in the arid metropolis about 275 miles (450 km) from the US border believe if Torreon cannot defeat the Zetas soon it may need to reach some kind of agreement with their arch rivals, the Sinaloa Cartel, and let them do the job. Widely seen as the most brutal Mexican drug gang, the Zetas have so terrorised Torreon and the surrounding state of Coahuila that some officials make a clear distinction between them and the Sinaloa Cartel, for years the dominant outfit in the city.

"They (the Zetas) act without any kind of principles," Torreon's police chief, Adelaido Flores, told Reuters. "The ones from Sinaloa don't mess ... with the population."

Local politicians tacitly admit that deals with cartels, often unspoken, helped keep the peace in the past, before a surge in violence prompted President Felipe Calderon to mount a military-led crackdown against organized crime six years ago.

Calderon's forces have captured or killed many top capos around Mexico, but the campaign triggered fresh turf wars and a sharp increase in bloodshed, spearheaded by a new generation of criminals like the Zetas.

Over 60,000 people have been killed in Mexico in drug-related violence during Calderon's presidency. In Torreon, the Zetas took control of the local police, and in March 2010 they invaded city hall to demand that Mayor Eduardo Olmos sack the army general he had hired to clean up the force.

"You can't say that the police was infiltrated by organised crime - the police was organized crime," Olmos said. Subsequently, all but one of the 1,000-strong force were fired or deserted, and for a week Villa and his bodyguards were the only police.

At first, the city behaved "marvelously," said Olmos. Then the shootings, armed robberies and kidnappings took off as the gangs turned Torreon into a killing factory. According to local newspaper El Siglo de Torreon, there were 830 homicides in the first nine months of 2012 in the city's metropolitan area, home to just over 1 million people.

Higher murder rate

Greater Torreon had 990 killings in 2011, up from 62 in 2006. It now has a higher homicide rate than Ciudad Juarez, long Mexico's murder capital. Only Acapulco's is worse. Flores insists that better days lie ahead, saying the Zetas have been weakened by security forces and by the Sinaloa Cartel, run by Mexico's most wanted man, Joaquin "Shorty" Guzman. More than 90% of the hundreds of suspected gang members killed or arrested in Torreon this year have been Zetas, according to estimates by city authorities.

"They're nearly being finished off here," said the soft-spoken Police Chief Flores, standing on a hill above the city and gesturing at its impoverished western fringes. Towering above him, a 72-foot (22-meter) statue of Jesus Christ with outstretched arms gazes across the urban sprawl that is now the bloodiest battleground in the Zetas-Sinaloa conflict. Despite the setbacks this year, the Zetas still control Torreon's prison, police and the mayor's office say. Lying at the crossroads between Mexico's Pacific states and Ciudad Juarez and Monterrey, and linking the south to the US border, Torreon has long been a strategic hub for drug runners.

Locals say traffickers co-existed peacefully with legitimate businesses when Guzman's gang dominated here. At the very least, senior politicians in Coahuila have looked the other way, while some actively colluded with gangs, local leaders say.

"They're up to their necks in it, from the top down," one local business executive said of the politicians. "But don't put my name down or they'll be sending flowers to my grave."

When Calderon took office in 2006, voters like 53-year-old Torreon housewife Rosaura Gomez supported his conservative National Action Party (PAN) for taking on drug traffickers. But as the violence intensified and got closer to home, she lost faith. In this year's presidential election, Gomez backed the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, which ruled for most of the 20th century, in the hope that it can restore order. The party won the election and will return to power in December. "Before, there was a pact, and things were calm. The drugs went to the United States and these groups didn't mess with the people. This is what we want so we can live in peace," she said.

Suffering economy

Today, the economy is suffering. Garbage blows down the streets of Torreon's old town, passing shuttered businesses. The construction industry estimates about half the building firms are out of work in a city that had near full employment in 2000.

Private-sector investment is on track to drop by nearly a third from 2011. New job creation is heading for a 40-percent fall to about 4,800 - in a city growing by 12,000 people a year. Big foreign firms are tight-lipped about the violence. A Caterpillar official said the company's security costs had risen, but that its business had not been affected.

One top business executive, who asked to remain anonymous, says many acquaintances have left to escape the violence. Wearing a pained expression, he tells how a kidnapped friend had to give the names of other suitable victims to his captors as part of the ransom.

His name was among the five given. Despite that, the businessman argues that the crackdown on drug trafficking has been disastrous for his city, forcing gangs to resort to ever-more violent forms of money making. He and many other locals look back to the days when a "Don't ask, don't tell" attitude prevailed and business was good. President-elect Enrique Pena Nieto, who takes office on Dec. 1, has rejected negotiating with the gangs, mindful of the PRI's past reputation for cutting deals. But he stresses his priority is reducing the violence, then taking on the drug traffickers. In private, some officials here say it may be impossible to avoid tacit deals with the cartels in certain areas unless the violence is curbed quickly. That means hammering the Zetas.

Deals with the gangs

"I think the whole country wants the Zetas exterminated," said Raul Benitez, a security expert at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). "And if he's successful, Pena Nieto will have the support to do what he wants with his drug war."

Polls show a large majority of Mexicans reject deals with the gangs, but a 2011 survey in the hard-hit state of Chihuahua next to Coahuila showed nearly 50 percent favored a pact. The survey did not include Coahuila, where the Zetas' blend of co-option and coercion has become a serious embarrassment. Several former state officials are under investigation by federal prosecutors on suspicion of working for the drug gang.

On Oct. 7, marines killed Zetas leader Heriberto Lazcano in the state. Then his body was stolen from a funeral home by armed men. When Torreon's Mayor Olmos began to root out the Zetas, the police went on strike.

Calling a meeting in his office, he soon realised the officers who arrived were working for the enemy. He described how a policeman slouched in a chair and wearing sunglasses held up a phone so that the Zetas at the other end could hear every word the mayor said.

When Olmos refused to sack the police chief, General Bibiano Villa, masked Zetas surrounded his office, lining the stairs and the streets outside.

With the help of the media, Olmos broke the strike and forced all the police to take "loyalty tests."

Only one, a woman, passed. He then rebuilt the force with recruits from outside Coahuila and the army, and bumped up pay by 50 percent or more. But infiltration is a "permanent problem," he says.

Olmos, whose father was kidnapped by a gang in 1996, says the cartels are "equally bad" and opposes making deals. But he admits there is growing public pressure to end the violence.

Even some politicians from Calderon's PAN wonder whether a review of the drugs policy is needed to pacify hard-hit areas. "I think a lot of people think negotiating with certain groups may resolve this problem," said Rodolfo Walss, a PAN city councillor in Torreon.

"Frankly, I don't know." Back on the Cerro de las Noas hill, where the huge concrete statue of Christ looms above the city, the attitude of salesman Jose Angel Aguirre sums up the conundrum facing Torreon.

Saying "I would rather bury my son today than discover he was out there killing" for a drug cartel, Aguirre conceded he would accept the presence of one gang if it improved security. "It would be better if one of the two sides won," the 58-year-old said. "Then there would be peace."

![submenu-img]() Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins

Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins![submenu-img]() Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'

Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'![submenu-img]() India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat

India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat![submenu-img]() Vellore Lok Sabha constituency: Check polling date, candidates list, past election results

Vellore Lok Sabha constituency: Check polling date, candidates list, past election results![submenu-img]() Meet NEET-UG topper who didn't take admission in AIIMS Delhi despite scoring AIR 1 due to...

Meet NEET-UG topper who didn't take admission in AIIMS Delhi despite scoring AIR 1 due to...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Tanvi Hegde? Son Pari's Fruity who has worked with Shahid Kapoor, here's how gorgeous she looks now

Remember Tanvi Hegde? Son Pari's Fruity who has worked with Shahid Kapoor, here's how gorgeous she looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Kinshuk Vaidya? Shaka Laka Boom Boom star, who worked with Ajay Devgn; here’s how dashing he looks now

Remember Kinshuk Vaidya? Shaka Laka Boom Boom star, who worked with Ajay Devgn; here’s how dashing he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

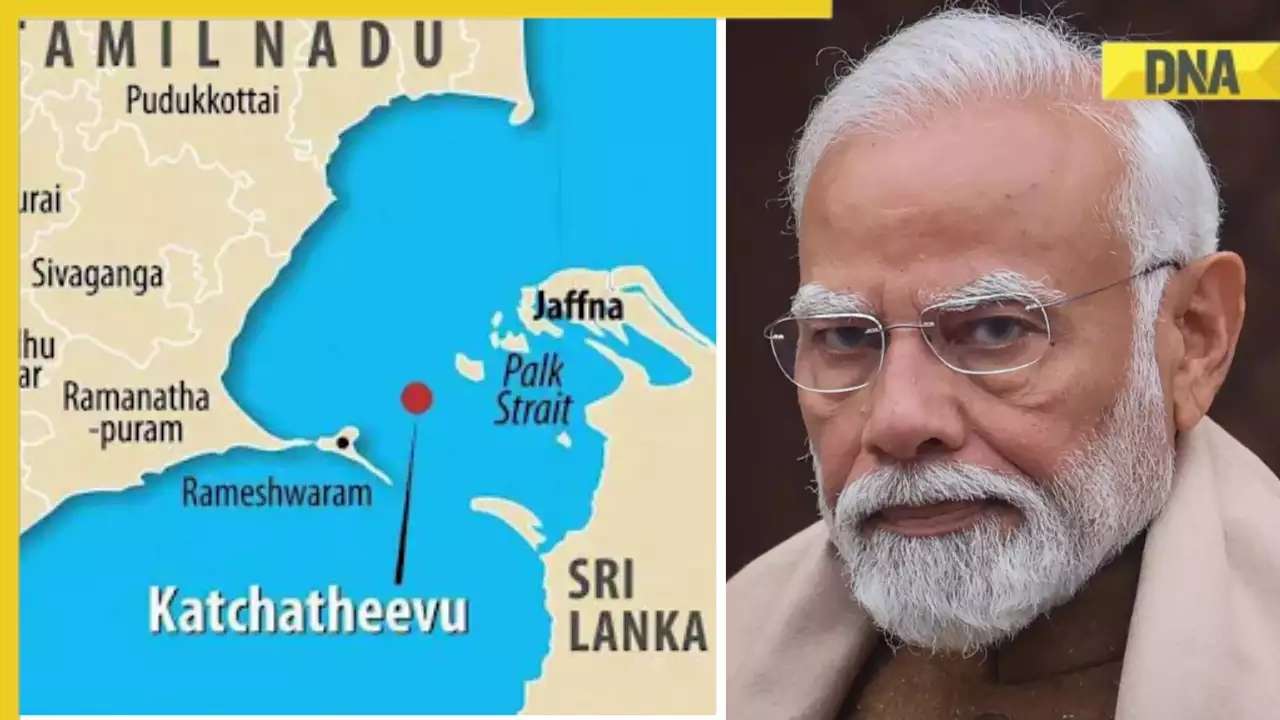

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Reason behind caused sudden storm in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur

DNA Explainer: Reason behind caused sudden storm in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur![submenu-img]() Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins

Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins![submenu-img]() Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'

Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'![submenu-img]() India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat

India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat![submenu-img]() This film has earned Rs 1000 crore before release, beaten Animal, Pathaan, Gadar 2 already; not Kalki 2898 AD, Singham 3

This film has earned Rs 1000 crore before release, beaten Animal, Pathaan, Gadar 2 already; not Kalki 2898 AD, Singham 3![submenu-img]() This Bollywood star was intimated by co-stars, abused by director, worked as AC mechanic, later gave Rs 2000-crore hit

This Bollywood star was intimated by co-stars, abused by director, worked as AC mechanic, later gave Rs 2000-crore hit![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

RCB vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Sunrisers Hyderabad ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Phil Salt, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 8-wicket win over Lucknow Super Giants

IPL 2024: Phil Salt, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 8-wicket win over Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Why are Lucknow Super Giants wearing green and maroon jersey against Kolkata Knight Riders at Eden Gardens?

IPL 2024: Why are Lucknow Super Giants wearing green and maroon jersey against Kolkata Knight Riders at Eden Gardens?![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Shimron Hetmyer, Yashasvi Jaiswal power RR to 3 wicket win over PBKS

IPL 2024: Shimron Hetmyer, Yashasvi Jaiswal power RR to 3 wicket win over PBKS![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)