A Swedish pop music tycoon turned TV celebrity who once founded an anti-immigration political party might well be the most unlikely beneficiary of Europe's migration crisis.

A Swedish pop music tycoon turned TV celebrity who once founded an anti-immigration political party might well be the most unlikely beneficiary of Europe's migration crisis.

But as long as the country is taking in the most asylum seekers per capita of any in Europe, Bert Karlsson is happy to earn a fortune from the government for housing them. Sweden's answer to Simon Cowell, Karlsson founded a record label and later appeared as a ubiquitous judge on reality TV talent shows.

He launched an anti-immigration political party that briefly held the balance of power in parliament before flaming out in the mid-1990s, and still says Sweden needs to spend less on refugees.

But that hasn't stopped his company, Jokarjo, from housing around 5,000 refugees at 30 sites, becoming the leading supplier of temporary asylum seeker housing to Sweden's government, a business he expects to double in 2015 after tripling in 2014. "I'm the best in Sweden at entrepreneurship," he proclaims, sounding a bit like Donald Trump, a figure whose anti-establishment moxie he says he admires, as he speeds from his native town Skara to his first and biggest site for refugees.

The venture is a reminder that the European refugee crisis is also big business, from the Turkish market traders selling life vests on the beach in Bodrum, to the Balkan coach operators selling bus tickets from border to border.

With one hand driving his Saab - plastered with stickers from his lakeside summer resort - and the other holding an iPhone discussing business, Karlsson says he spotted the need for immigrant housing early and set out three years ago to provide it at half the price the state was paying at the time.

Sweden, a country of just 9.8 million people, received 81,000 refugees in 2014 and is on course to top that in 2015. The government has pencilled in 40 billion Swedish crowns ($4.8 billion) to spend on immigration and integration, around 4% of Sweden's total budget for 2016.

Having run out of apartments for asylum seekers, the Swedish Migration Agency has been paying companies to house them in buildings like unused hotels and hostels. The growing field has attracted some of the country's major names, including the Wallenbergs, Sweden's most prominent industrialist family. But none has taken a bigger slice of the pie than Karlsson's Jokarjo, which billed the migration agency 170 million crowns for temporary shelter so far this year alone, more than three times as much as its biggest competitor.

The migration agency believes housing for asylum seekers will cost 3 billion Swedish crowns in 2015, not including the cost of looking after unaccompanied children.

Children

Stopping in a cafe to down three cups of coffee while trading stocks over the phone, Karlsson chatted to an Iranian immigrant working at the cashier's till. He ended up offering him a job, either at one of his asylum homes or his food plant.

Residents waved as Karlsson arrived at Stora Ekeberg, a former sanatorium in the countryside which now houses more than 500 refugees from countries such as Syria and Iraq. Inside, children from Somalia were playing table tennis, while other residents worked out in the gym. Corridors and spaces were clean and the atmosphere relaxed.

Despite the money he has earned off Sweden's well-publicised generosity to refugees, he was still critical of the lavish government expenditure. "If they want the Sweden Democrats at 50%, they should continue on the exact same course," he said, referring to the rise of the anti-immigration party that became Sweden's third biggest in elections 2014.

Sweden has long prided itself on its reputation for taking in refugees. A former prime minister proclaimed the country a "humanitarian superpower".

Since the civil war began in Syria four years ago it has been out in front of its EU neighbours in offering Syrian refugees immediate permanent resident status and allowing them to swiftly bring family members to join them. But a growing minority of Swedes say such policies are simply unsustainable.

Karlsson himself has stayed out of politics since his own populist anti-immigration party, New Democracy, collapsed in infighting.

It peaked in the general election of 1991 when it won 6.7% of the vote and 25 seats in parliament, the same year that Carola Haggkvist, Karlsson's biggest musical act, won the Eurovision song contest. Three years later the party lost all of its seats and never recovered.

BALLOONING COST

Karlsson says his company saves Sweden money by housing asylum seekers more cheaply than competitors. He criticised government costs for care for unaccompanied children seeking asylum, which he said he could do at a quarter of the 1,900 crowns per day ($225) the migration agency pays municipalities per child.

More than 12,500 such children have already arrived since the start of the year, more than the agency pencilled in for all of 2015 at an estimated cost of 9.1 billion crowns in its latest forecast just two months ago.

Karlsson's competitors include care provider Attendo, owned by private equity firm IK Investment Partners. Aleris, the healthcare firm owned by the Wallenberg family's investment vehicle Investor AB, operates six homes for unaccompanied asylum seeking children.

In the first eight months of this year, the migration agency paid out 894 million crowns to the 50 biggest suppliers of temporary housing for refugees, already close to the 1 billion crowns for all of 2014. Nearly a fifth of that went to Jokarjo. "We are satisfied with Jokarjo. We are satisfied with most suppliers," said Tolle Furugard, who oversees housing for asylum seekers at the migration agency. "It is often said in the debate that they are unserious dealers just out to make money, but that's not our view."

Most Swedes accept the role of private business in housing refugees, but there has been an outcry against exorbitant fees charged to overwhelmed municipalities. The town of Molndal in southwestern Sweden has had to pay around 50,000 crowns per month for one-room apartments for youths in some cases.

"It's not ok. But it is an emergency solution," said Marie Osth Karlsson, no relation to Bert, who chairs Molndal's municipal board.

Having opened five new sites over the previous week, Karlsson said he had 12 additional facilities ready to take on 2,000 or more refugees over the coming weeks. One things seems certain - demand will remain strong. ($1 = 8.3491 Swedish crowns)

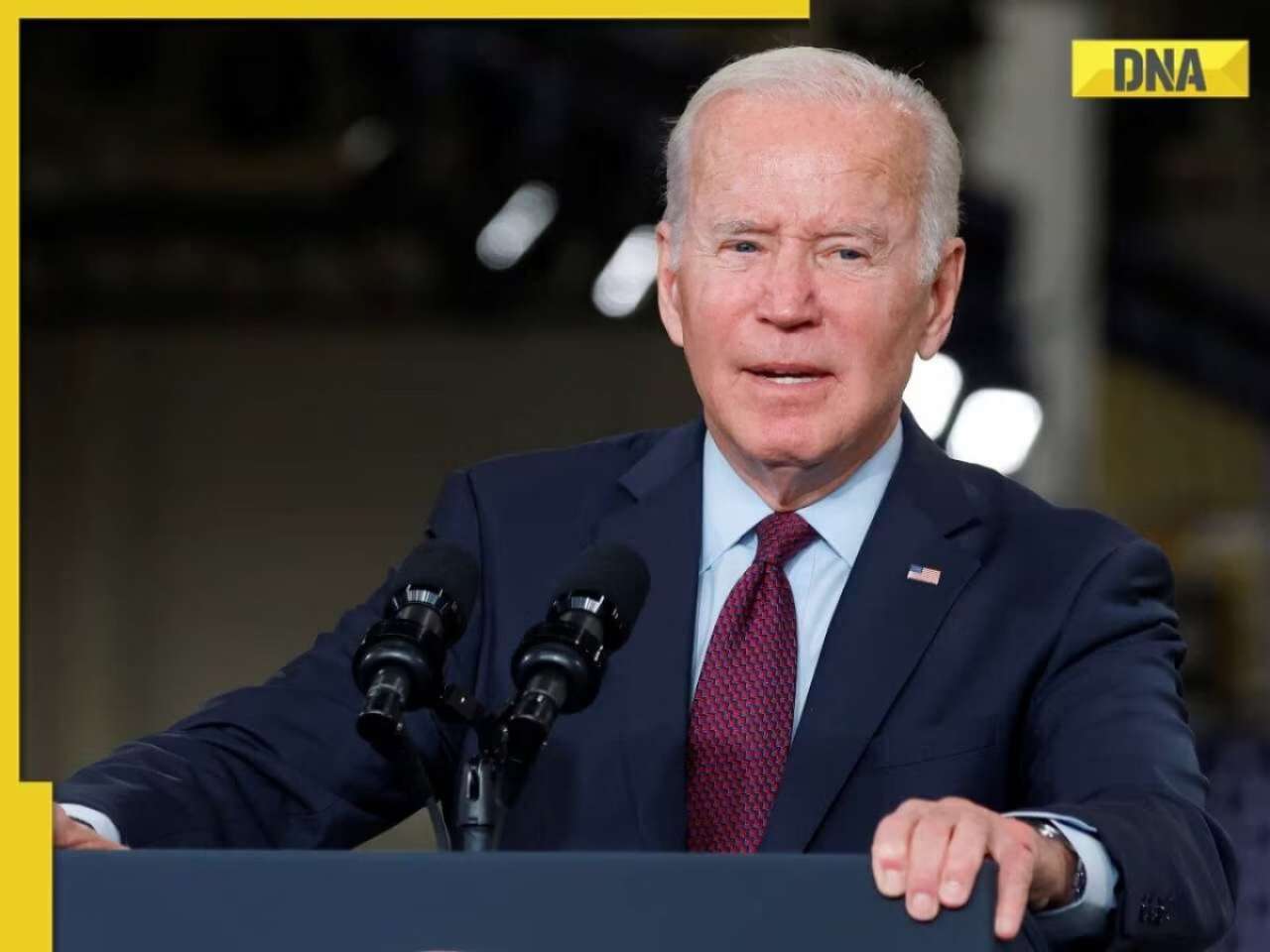

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)