What was the theory Prof Higgs proposed? Peter Higgs was among a group of six theoretical physicists who, in 1964, independently proposed a theory to explain how the building blocks of the universe have mass.

Without the influence of a mysterious field spread across the universe, now known as the Higgs field, particles would simply whizz around space at the speed of light rather than clumping together and forming the building blocks of atoms.

Higgs was not the first to mention this invisible field, but he was the first to propose a mechanism by which it could be detected - by a signature massive particle, or boson, that would accompany it. Why did the particle take so long to find?

Higgs boson is extremely unstable and collapses into smaller particles almost as soon as it is created. Not only would scientists have to create the particle, they would not be able to detect it directly.

They would have to infer its presence from the smaller particles created when it breaks up. Only recently has there been equipment powerful enough to do this, inside the particle accelerator at Switzerland's Cern laboratory, known as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

How did they find the Higgs boson?

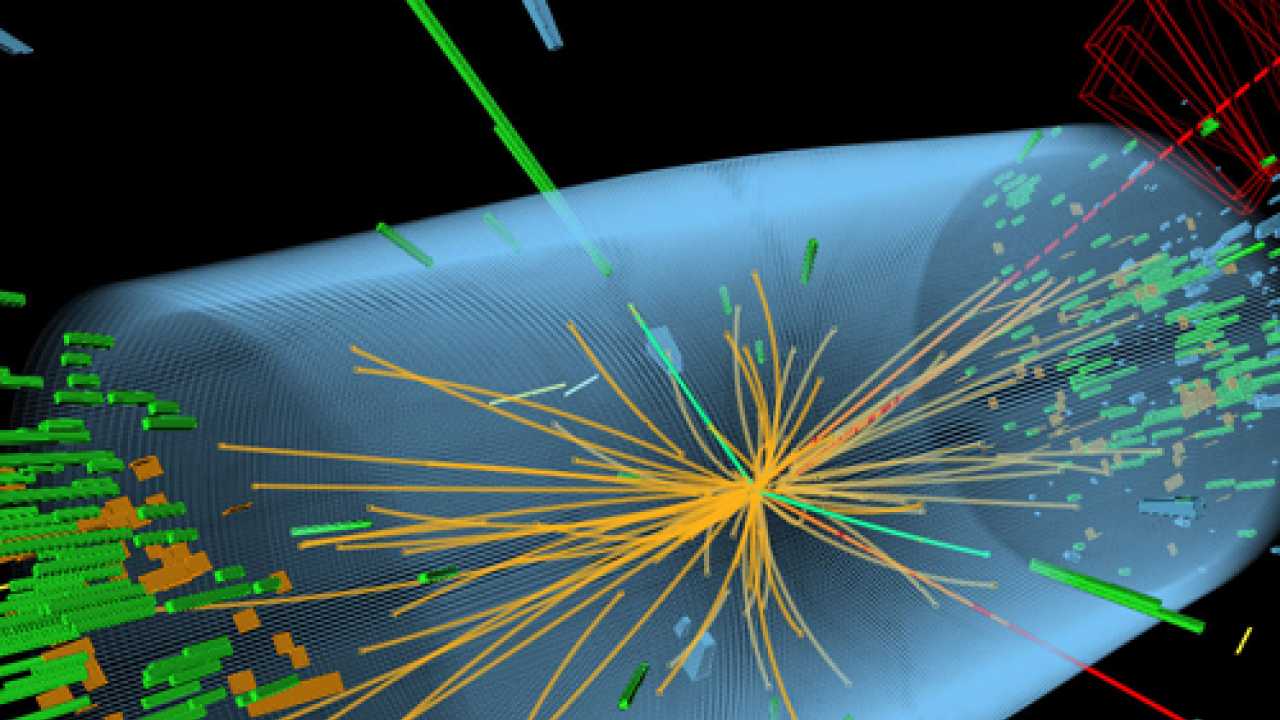

Engineers smashed beams of particles known as protons together at close to the speed of light inside the LHC. But for every 10 billion collisions of particles, only one is likely to produce a Higgs boson, which will instantly decay into smaller component particles.

Scientists were able to identify a handful of events that produced a Higgs boson after analysing several years' worth of collisions. Why is it so important?

The Higgs boson has been described as the "missing piece" of the Standard Model, which explains how the parts of the universe that we understand interact with one another. The particle proves the existence of the Higgs field. However, our knowledge of particle physics is far from complete. The model accounts for less than 5 per cent of the universe, with further mysteries such as the nature of so-called dark matter and dark energy still to solve.

What has finding the particle achieved?

Aside from advancing the understanding of the universe and how it works at a fundamental level, not much. The hunt for the Higgs boson was a triumph for basic science but is unlikely to have immediate and practical applications. Until physicists learn more about the Higgs boson and its properties, it is impossible to say the areas where it could prompt a breakthrough. Nick Collins

Shy celebrity Professor bemused by his fame

In the weeks before the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Cern was turned on for the first time, Peter Higgs made an unannounced visit to the facility. As word got around that Prof Higgs was in the Swiss research centre, there was a buzz of excitement akin to the arrival of a Hollywood celebrity.

The Daily Telegraph was touring the LHC at the same time as Prof Higgs's first visit in 2008 and joined him. He appeared awestruck by the scale of the equipment that would be used to prove his theory, to explain how the basic building blocks of the universe are held together and given mass.

As a theoretical physicist, his tools had been pencil and paper rather than the 17-mile particle accelerator and the cathedral-sized detectors used at Cern. He also seemed bemused by the number of physicists, engineers and PhD students who rushed up to him, brimming with enthusiasm.

For a retired grandfather who lives alone in a modest flat in Edinburgh's New Town, it was a little overwhelming. Four years after his first visit to the LHC, Higgs was back at Cern in an auditorium full of scientists as the results that all but proved the existence of the particle were announced.

The room exploded with applause and cheers, while Prof Higgs wiped away a tear. He refused to bask in the glory and paid tribute to the 2,000-odd scientists who had worked on the Atlas and CMS experiments at Cern, which were responsible for proving the existence of particle.

Prof Higgs, a father of two and a grandfather of two, has never been comfortable with the fame his theory brought him. Born in Newcastle in May 1929, he has been enthralled by physics since he was a schoolboy and enjoyed the quiet but competitive world of academia. Now, people recognise him on the street and he is besieged with interview requests. He has previously said winning a Nobel Prize would be "gratifying" and an "ordeal" due to the number of events he would have to attend.

Higgs separated from his late wife Jody, an American linguist, in the 1970s. At the age of 84, he is not as sprightly as he once was, recently suffering poor health that forced him to cancel some public appearances. But his mind is still as sharp as ever and he has a formidable memory that brims with facts, anecdotes and humour.

Dr Alan Walker, Prof Higgs's friend, said: "I've heard Peter give so many interviews and talks I often feel like I know exactly what he is going to say, but he still surprises me." When asked how he felt about the new particle being found when it was announced last year, Prof Higgs answered: "It's very nice to be right sometimes."