An avalanche of bad economic news, compounded by gross macroeconomic mismanagement, threatens to reduce India’s status as a respectable investment destination for global funds

Downgrade will up borrowing costs abroad, deter investors

MUMBAI: An avalanche of bad economic news, compounded by gross macroeconomic mismanagement, threatens to reduce India’s status as a respectable investment destination for global funds, earned barely 18 months ago, to junk status.

Rating agency Standard & Poor’s on Friday flagged India’s worsening inflation scenario and credit profile, characterised by rising fiscal deficits (the gap between government spending and its total expenditure, which has to be bridged by borrowings), raising the prospect of a downgrade of India’s sovereign rating from ‘investment’ to ‘speculative’ grade (i.e. junk).

S&P had rated Indian local debt at investment grade, or BBB-, for the first time on January 30, 2007, up from BB+. If the rating falls again to BB+, the world’s big pension funds and risk-averse investors will start giving India a miss. A downgrade would also means companies and banks here will have to pay higher interest rates on their overseas loans. Rates on loans are pegged to country ratings.

This and other bad news —including faltering industrial production, a rise in inflation and crude oil prices — plunged the BSE Sensex by 456 points.

India’s industrial output growth fell sharply to a six-year low of 3.8% in May from 6.2% in April. “The data suggests that the trade-off between rising inflation and falling growth is worsening,” notes Lehman Brothers’ economist Sonal Varma. “Between the hard choice of rising inflation and slowing growth, we expect the Reserve Bank of India to choose (tackle) inflation.” This means still higher domestic interest rates.

“The combination of industrial production numbers and the news of a further move-up in wholesale price inflation to 11.9%... emphasises the policy dilemma facing the RBI,” says HSBC’s India economist Robert Prior-Wandesforde. “Overall, the RBI is likely to retain a tightening bias.”

Summing up the grim mood, Barclays Capital regional economist Sailesh Jha said: “Recent developments in India lead us to a more bearish assessment of the macroeconomic outlook. Inflation will continue to accelerate, fiscal risks are picking up and financial asset prices are headed south.”

“Failure to respond adequately to negative developments as they arise… could point to a sustained deterioration in macroeconomic stability and… increase the probability that the ratings could be lowered,” S&P’s analyst Takahira Ogawa noted in a report.

The other global rating agency, Moody’s, currently maintains a stable rating on India’s foreign exchange exposure and on domestic debt. The agency’s India representative Chetan Modi said he would not comment on revisions - or even the possibility of one.

A sovereign downgrade reflects a thumbs-down for the management of India’s political economy. HDFC Bank treasurer Sudhir Joshi notes that although a downgrade is not imminent, it would have negative consequences.

“Two things will happen in the event of a downgrade,” says Prakash Subramanian, managing director and regional head, capital market, South Asia, Standard Chartered Bank. “Appetite for Indian paper globally will go down. Credit spreads will widen further, and domestic liquidity will suffer, forcing the government to revisit the ceiling on external commercial borrowings. Indian companies’ cost of borrowing will go up by 100 basis points or more (100 basis points equal 1%).”

S&P’s had raised India’s sovereign rating to ‘investment’ grade in January, 2007, citing strong GDP growth, gradual reforms and “consistent monetary and fiscal policy stances”, which had “sustained macroeconomic stability”.

What has changed since then? For one, global oil and food prices have soared, and with it the burden of subsidies borne by the central government, which has played havoc with the fiscal deficit. Add to that the impact of additional - some would say ‘profligate’ - expenditure measures such as a Rs 60,000 crore farmers’ debt waiver programme announced in Budget 2008, and the provisions of the Sixth Pay Commission for government employees, and the fiscal deficit “could exceed 9% of GDP” in 2008-09, notes Ogawa.

On Friday, global crude oil prices edged close to $147 on sustained geopolitical tension centred on Iran’s recent missile tests. The longer oil prices stay at those high levels, the more serious the implications for India’s fiscal deficit, particularly since a government in election mode may not be overly concerned about fiscal or monetary slippages. “The government is walking a tightrope because it cannot hike oil prices, and a duty cut will mean revenues will have to be sacrificed,” notes Subramanian. “It will have to absorb the burden in some way.”

Dhiraj Sachdev, head, PMS, HSBC Asset Management said the market had been spooked by the “I-4” factor - “IIP numbers, inflation, Infosys results and Iran tension” - but lower-than-expected industrial production data had probably done the most damage. “Also the fact that Infosys did not revise its dollar guidance impacted the market.”

Amitabh Chakraborty, president-equities, Religare Securities, too, said the IIP numbers did the damage. Other analysts see crude oil prices as the “mother of all problems”.

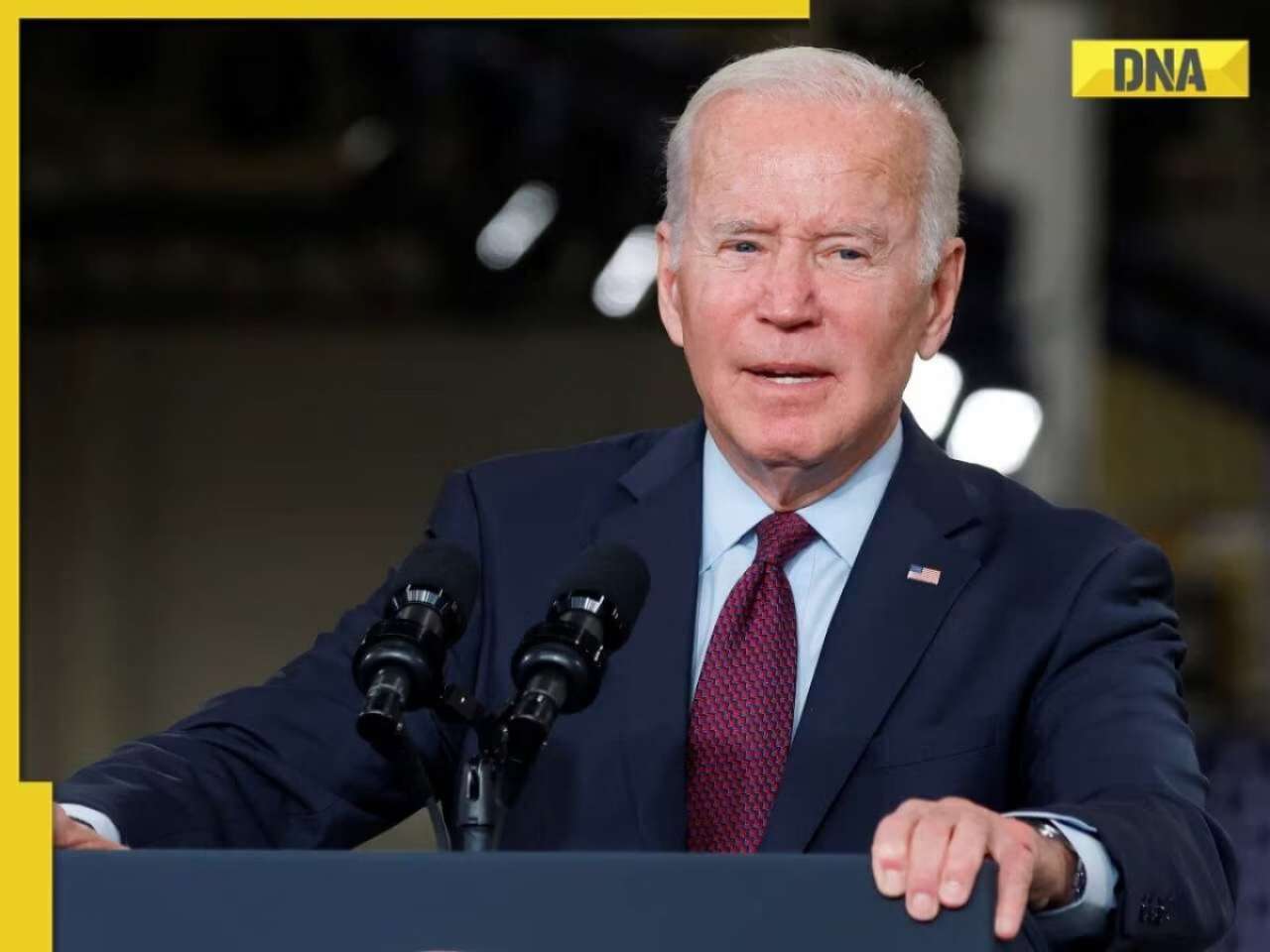

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)