Crowded, narrowing and, in some places, missing altogether. Suparna Thombare and Divya Subramaniam report on how our footpaths are being driven into extinction

Kushroo Munshi loves his evening walks. Though there is bright sunlight, the leafy banyan trees planted along the pavement offer enough shade to the 63-year-old Five Gardens resident. “There are vehicles, but they don’t get in our way. Thanks to the pavements here, people can walk about and sit and chat with their friends,” he says.

This delightful picture painted by Munshi is however fast facing extinction in Mumbai’s scramble for space. It is the exception in a bustling city where the norm is the scene at Chembur’s Sahakar Junction, where senior citizen R Krishnan was knocked down by an auto rickshaw during his morning walk. Dealt severe head injuries and bruises, Krishnan had been walking on the road, because there was no space on the pavement.

Hawkers, car parks, building projects and poor planning are starving the city of crucial pavement space, turning the city into a living hell for pedestrians. “I have to walk on the road as the pavements are always full of cars and two-wheelers,” says Shikha Sen, 63, a resident of Bandra Reclamation, who ended up with a scraped knee because of a passing auto rickshaw. “Things get so bad that I can’t even walk to the grocery store.”

As visions of turning Mumbai into Shanghai all look upward at skyscrapers and flyovers, the pavements beneath us have been completely ignored. The McKinsey report, Vision Mumbai, which outlines ways to make Mumbai a world-class city, does not even mention pedestrians.

Mumbai’s pavements are not merely a space for pedestrians to walk on; they enrich the life of the surrounding community. The pavement booksellers, who have been selling second-hand books for decades, are a familiar and comforting sight for the residents of King’s Circle. Ruia College students have special memories too, formed on the ‘katta’ (the long low wall outside Matunga Gymkhana) and the pavement opposite their college. “My father spent all his college years hanging out on the sidewalks here,” laughs Rupa Vishwanathan, a student of Ruia College. “This isn’t just a pavement for us.”

While inhabitants of Matunga and Five Gardens are lucky to still have the luxury of pavements, Bandra’s Hill Road is not as blessed. Fed up with the stress he endures every time he walks down the road, resident Manav Khedkar says, “Public bodies need to think like a pedestrian to find a solution.”

Too many of Mumbai’s pavements are too narrow, making pedestrianism almost impossible. KV Krishna Rao of the Standing Technical Advisory Committee, who has been appointed by the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) for advice on road construction, designing, maintenance and development, says the minimum and average size for a pavement in the city is 1.5m and 2m, respectively. “But this needs to be altered according to pedestrian volume which is often neglected.”

The few areas that still have wide pavements are finding them gradually being turned into parking lots. “Pavements in the city are being made for cars not pedestrians,” says Prasad Shetty, executive-member, Collective Research Initiatives Trust, a Mumbai-based research organisation. “Rather than acting as a space for pedestrians, they are being used as a means to keep people and other things off the roads.”

“Another big problem is shabby repair work. The BMC is supposed to follow certain guidelines while doing repair work,” says Bhaskar Prabhu, an activist who has also filed numerous RTI (right to information) applications about the conditions of roads.

So what is it that hapless pedestrians and residents can do to save pavements from being eaten up by the city? GR Vohra, secretary of the Flank Road Citizens Forum in Matunga, says constant pressure on the authorities is the key. “Relentless vigilance by residents is the reason the Five Gardens area still has pavements,” he says. Neera Punj of CitiSpace, an NGO fighting for the retention of spaces for pedestrians in the city, says, “It’s because of citizens’ apathy that encroachments have become such a problem.” Adds activist Bhaskar Prabhu, “Citizens should network with the Citizen's Road Committee, who can then check on the state of the pavements and question the authorities.”

The authorities too seem to recognise the problem and the need for solutions. Rao says that for Mumbai to become a truly liveable city, it needs good pavements. “The Central government has said that all future funding for road projects will depend on how pedestrian-friendly they are, so MCGM’s future plans will have to consider the rights of pedestrians,” he says.

Municipal commissioner Johny Joseph says, “We have allotted Rs25.9 crore this year for the construction and improvement of footpaths in Greater Mumbai.” According to additional commissioner Shrikant Singh, the BMC is trying to map storm-water drains, pipelines and utility lines so that pavements do not lie dug up indefinitely.

But until these plans fall into place, it appears that pedestrians in the city just have to steel themselves for a walk on the wild side.

![submenu-img]() Rakesh Jhunjhunwala’s wife sold 734000 shares of this Tata stock, reduced stake in…

Rakesh Jhunjhunwala’s wife sold 734000 shares of this Tata stock, reduced stake in…![submenu-img]() West Bengal: Ram Navami procession in Murshidabad disrupted by explosion, stone-pelting, BJP reacts

West Bengal: Ram Navami procession in Murshidabad disrupted by explosion, stone-pelting, BJP reacts![submenu-img]() 'We certainly support...': US on Elon Musk's remarks on India's permanent UNSC seat

'We certainly support...': US on Elon Musk's remarks on India's permanent UNSC seat![submenu-img]() Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’

Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore

Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’

Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore

Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore![submenu-img]() India's first female villain was called Pak spy; married at 14, became mother at 16, left family to run away with star

India's first female villain was called Pak spy; married at 14, became mother at 16, left family to run away with star![submenu-img]() Dibakar Banerjee says people didn’t care when Sushant Singh Rajput died, only wanted ‘spicy gossip’: ‘Everyone was…'

Dibakar Banerjee says people didn’t care when Sushant Singh Rajput died, only wanted ‘spicy gossip’: ‘Everyone was…'![submenu-img]() Most watched Indian film sold 25 crore tickets, was still called flop; not Baahubali, Mughal-e-Azam, Dangal, Jawan, RRR

Most watched Indian film sold 25 crore tickets, was still called flop; not Baahubali, Mughal-e-Azam, Dangal, Jawan, RRR![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: DC thrash GT by 6 wickets as bowlers dominate in Ahmedabad

IPL 2024: DC thrash GT by 6 wickets as bowlers dominate in Ahmedabad![submenu-img]() MI vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

MI vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() MI vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Punjab Kings

MI vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Punjab Kings ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Big boost for LSG as star pacer rejoins team, check details

IPL 2024: Big boost for LSG as star pacer rejoins team, check details![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR

IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Deserts around Saudi Arabia's Mecca and Medina are turning green due to…

Watch viral video: Deserts around Saudi Arabia's Mecca and Medina are turning green due to…![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

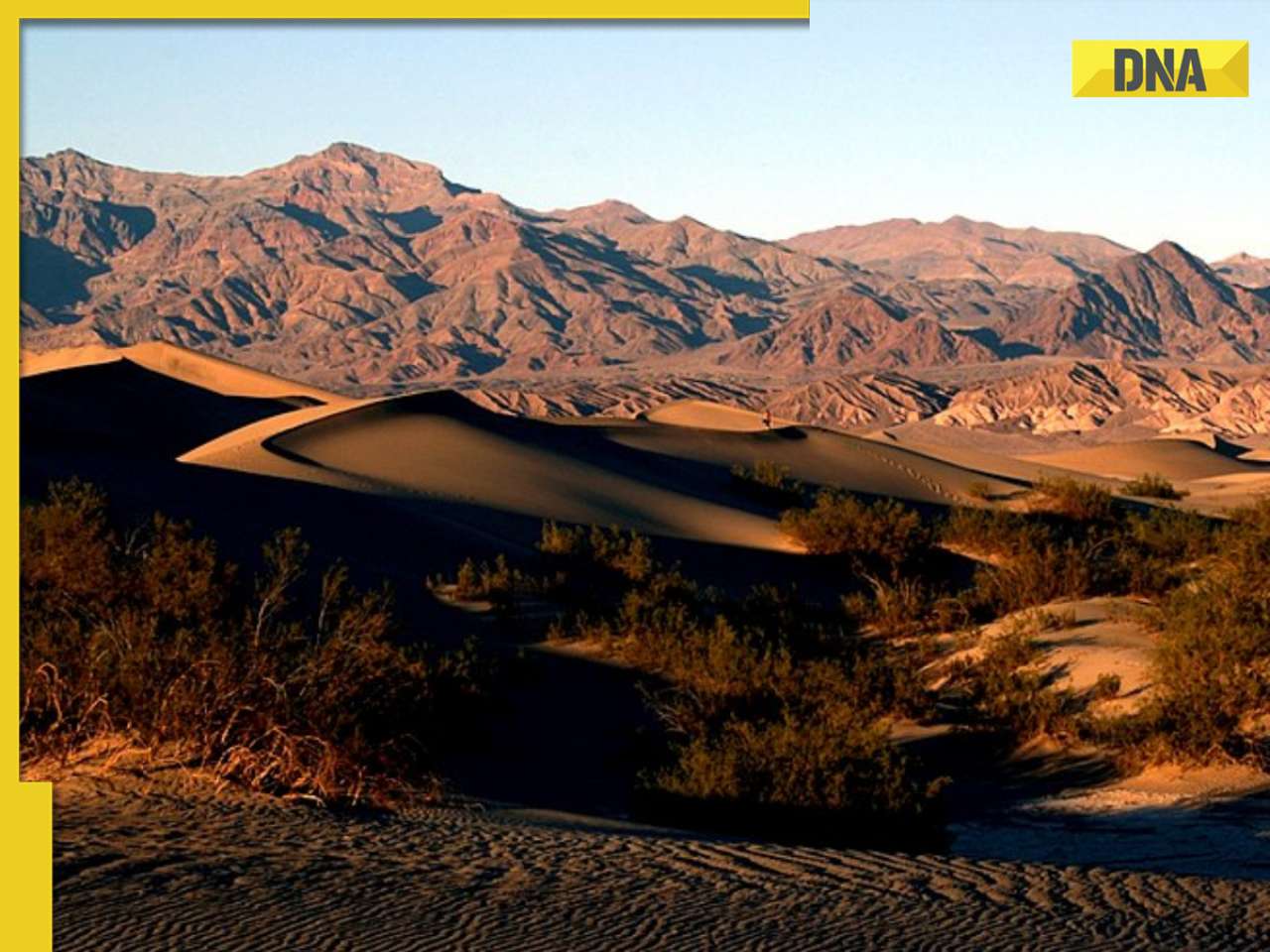

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here

Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

)

)

)

)

)

)

)