Does the movie make the man, or does the man make the movie? Does art imitate life or does life imitate art? We'd say that Indian cinema, like all cinemas, views the world through archetype, fantasy, prognostication and desire. In this sense, Amar Akbar Anthony is a dream world, brimming with symbolic possibilities drawn from the everyday realities of Indian life. As with a dream, one may leave a film with a sense of a renewed hope, or lingering dread. And if the film registers a desire for change, you can be sure there's already something of that in the world outside the cinema hall.

But these are generalities. To make the question specifically about film and romance is to raise the stakes, because in India, film has long played an outsized role in defining what love is supposed to look like between modern young people. There's no question that these representations can have a normative effect in society. How hard is it, for example, to imagine a Hindu-Muslim couple romancing each other with pet names like Veer and Zara? And yet, even this scenario is not a straightforward case of social practice being inspired by cinema. Part of what makes filmi romance so compelling is that it is a fantasy, and for most people it remains safely confined to the imagination. The same young men and women who get the thrills from the stars' onscreen flirtations generally go on to marry people chosen for them by their parents.

What is a nation? Long before Benedict Anderson, French thinker Ernest Renan called it "a soul" and a "spiritual principle" that united a group of people so that they cared about each other, even though they were otherwise complete strangers. Amar Akbar Anthony shows us Renan's idea in narrative form: three complete strangers discover that they are brothers.

There have been times everywhere in the world when nationalism has torn people apart, and there have been times when it brought people together. Indians have often come to understand themselves and their relation to others by engaging with texts. Mahabharata, Ramayana, Panchatantra, Jataka stories and Sufi romances, such as Padmavat and Madhumalati, all speak to an imagined community, and skillfully use stereotypes and stock characters to that end.

One of the extraordinary things about Manmohan Desai is that he tapped into this long history of imagining India. Imagining a community, in fact, is an essential part of being a social person. Your apartment complex, your neighbourhood, city or state, nation or planet: these are all collectivities in which your own ideas about belonging come together with those of others, to give meaning to the bonds that bring everyone together.

So the big question is, how you imagine the community, and whom you include or leave out. And we think this is the key message of the film. It's best to assume we are all brothers (and sisters) because it may turn out that, in fact, we actually are.

Hindi films, which have been produced in Bombay/Mumbai since sound came into the movies in the 1930s, are rich documents of the city's history. In several films of the 1950s, for example, Dev Anand stars as an urban hero whose adventures take him from Bombay — defined as "town" or the Mumbai city district — to wild, undeveloped areas that seem to be far away but are actually places such as Borivli or Goregaon. Amar Akbar Anthony, which was released in 1977, offers a sharp contrast between older suburbs such as Bandra, where most of the story unfolds, and outer suburbs such as Borivli, which at the time were just entering the process of development.

Take a look at the chase scenes in the movie and notice how many construction sites the cars are shown racing by. For us, the movie's end, where the three brothers and their brides drive up the highway and by the sunset, is symbolic of the shift to the outer suburbs as a base for a new Indian middle class that can transcend communal divisions.

The scene today is quite different. For one thing, Borivli has now been settled and while the national forest is still there, the "suburban" neighborhoods are as densely urban as any neighbourhood in Bandra or south Mumbai, for that matter. Speaking very generally, however, it seems to hold true for contemporary Bollywood films that the Mumbai suburbs (in a highly glamourised and sanitised depiction) continue to serve as the locus of aspirational lifestyle choices and upward mobility. What you don't often see in the movies is the extensive slums where at least half of the people actually reside in the Mumbai suburban district. Not everyone who lives in Borivli or Jogeshwari goes to the multiplex.

Many religious traditions maintain that a healthy mind needs a healthy body, and that "the body is a temple", as both Christians and Hindus have said. Physical development and bodily restraint have long been stressed as moral endeavours in various religious traditions. But the phenomenon of our interest really begins in the 19th century, when these moral projects became connected with political projects, both imperialist and nationalist. The ideal of the muscular Christian — an active man whose words and deeds were both clean and healthy — was central to the mystique and self-image of the Britishers who ran the Empire in India and elsewhere. And many Hindus encountered this ideal as a challenge, identifying the renewal of the Indian nation with revitalisation of the Hindu male body. It was in this connection that Mahatma Gandhi wrote in 1918: "It is easier to conquer the entire world than to subdue the enemies in our body. The self-government, which you, I and all others have to attain is in fact this. Need I say more? The point of it all is that you can serve the country only with this body."

At the same time, there were, and are, no more enthusiastic advocates of physical culture in India than the RSS.

To find such explicit links between physical, moral and social development in the context of Indian Islam, you would probably look to teachings about women, modesty and piety before turning to men and muscularity. But let's not downplay the role of Muslims in modern Indian physical culture, and specifically in wrestling.

The greatest historical wrestler the subcontinent has produced was the Great Gama, whose real name was Ghulam Muhammad. An international champion in the 1910s and 1920s, he was a symbol of Indian virility for Muslims and Hindus alike. Zabisko, the musclebound stooge of Amar Akbar Anthony, is named after Polish wrestler Zbyszko, whom Gama famously defeated. As for the greatest mythological wrestler the subcontinent has produced, that would of course be Lord Hanuman.

Most people in India are familiar with how Hanuman is shown in popular devotional art with the well-toned muscles of a weightlifter. But how many know that the model behind many contemporary poster images was P Sardar, a Muslim bodybuilder from Kolhapur?

Let's start with the imaginary Bombay of Amar Akbar Anthony. Anthonyville is a downmarket area that the Anthony character runs as the neighbourhood dada. The Muslim Quarter is centered on a timber bazaar and resembles Muslim-majority areas in real-life Bandra and Mahim. According to the film, both localities are parts of Bandra.

Our book argues that the film projects a narrative of historical progress onto spaces like these. As we suggested earlier, the Koliwada of Bandra is an unchanging zone of the past – a backward area – and Borivli is the example of a suburban community of the future. Ghettos such as Anthonyville and the Muslim Quarter, which are dominated by a Christian tough and a Muslim businessman respectively, are also examples of obsolete spaces, models of community to be consigned to the past. We can't build a modern India together, the film is saying, until we move out of these kinds of communally bound spaces.

And now to real life. Broadly speaking, the historical pattern has indeed been for migrants to cities to move in together with members of their own communities. This is the case especially for people from the poorer classes. In slum neighbourhoods, for example, caste and regional groups tend to be clustered together. But more privileged groups, such as Parsis and Saraswats, have also built self-segregated housing colonies in Mumbai. In fact, the city has always had Muslim quarters, Brahmin areas, and the like. And when the Britishers were in charge of urban planning in the 19th century, their "raj town" was sequestered from everything else, which they called the "native quarter". In effect, they dismissed the majority of colonial Bombay's diverse neighbourhoods as one giant ghetto.

But it won't do to be complacent about such urban segregation. Our forward-looking heroes of 1977 would surely be disturbed to discover how pervasive ghettoisation continues to be. Amar Akbar Anthony consigns such enclaves to the past, and beckons to a prosperous, secular future. The idea that any housing society would impose a ban on tenants because of their race, religion, or ethnicity is surely antithetical to Desai's vision. And no doubt, Amar, Akbar and Anthony would concur.

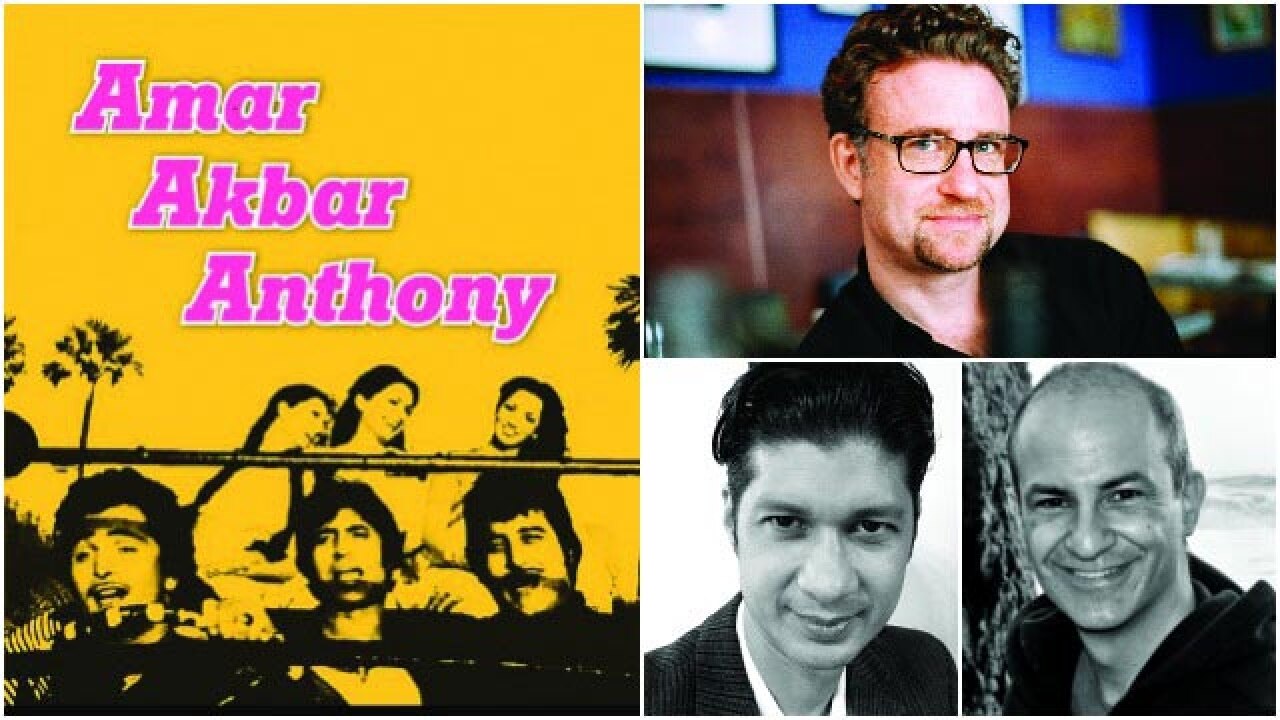

William Elison is senior lecturer in Religion, Anthropology and Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, US

Christian Lee Novetzke is associate professor of International Studies at the University of Washington

Andy Rotman is professor of Religion at Smith College, Massachusetts, US