The Reserve Bank of India has – once again – refused to lower interest rates.

Marketmen are a bit miffed. They had hoped that such a move could have spurred the stock markets to even greater heights. It might upset the finance minister who hoped that an interest reduction could nudge more investments into India, which in turn could create jobs.

But look at the predicament facing the RBI governor.

Most economists agree that governments -- the world over -- can either control interest rates or currency rates (against the dollar). But they cannot control both. At least not for very long.

The reason is simple. If a currency is undervalued -- like the rupee is -- it helps exporters and makes imports more expensive for the country. But it also puts pressure on the local currency to become as weak as the government claims it to be. One way in which equilibrium can be reached is by inflation rates going up. Higher interest rates 'devalue' the local currency.

Since the government wants a weaker rupee against the dollar to encourage exports, inflation is bound to remain like a coiled spring, waiting to pop out as soon as the controls are removed. High interest rates are one form of control that the RBI uses to keep the lid on currency exchange and inflation rates.

On the other hand, if the inflation rate is 6%, is it unfair to want to give small depositors at least a percentage more than the inflation rate? That is the only way the government can ensure that retirement and pension benefits are not eroded, and savings that the government wants to encourage so very badly do not take a hit.

Obviously, then, lending rates have to be a notch higher than deposit rates. And the spread between the two is the money that banks need to finance their operations. Banks also need to make a bit of additional surplus so that they can make good the sticky loans dispensed during the UPA regime.

That leads us to the next question. How weak is the rupee really?

One good way of judging this is by comparing per capital GDP with per capital PPP (price purchase parity (see table). The smaller the difference between per capita GDP and PPP, the more realistically valued the currency is. The huge difference in the case of India tells you that the rupee has been 'compelled' to remain weak. Its actual price purchase parity is almost four times higher.

Inflation would have been higher, had India's inherent productivity been weak. But productivity is on the upswing, as is evidenced by the recent increase in the PMI (purchasing managers index). Add to that the increase in foreign direct investment and investment inflows. All these should have made the rupee stronger.

Had the rupee been allowed to become stronger, the RBI would have had a good case for lowering interest rates. But it would have hurt exports, and made imports cheap. That could have hurt the current account deficit, right!

As things stand today, the situation is volatile. Either the rupee will strengthen, or inflation rates will climb. Naturally, the only thing the RBI can cling on to is interest rates. But not for long. Something will give way.

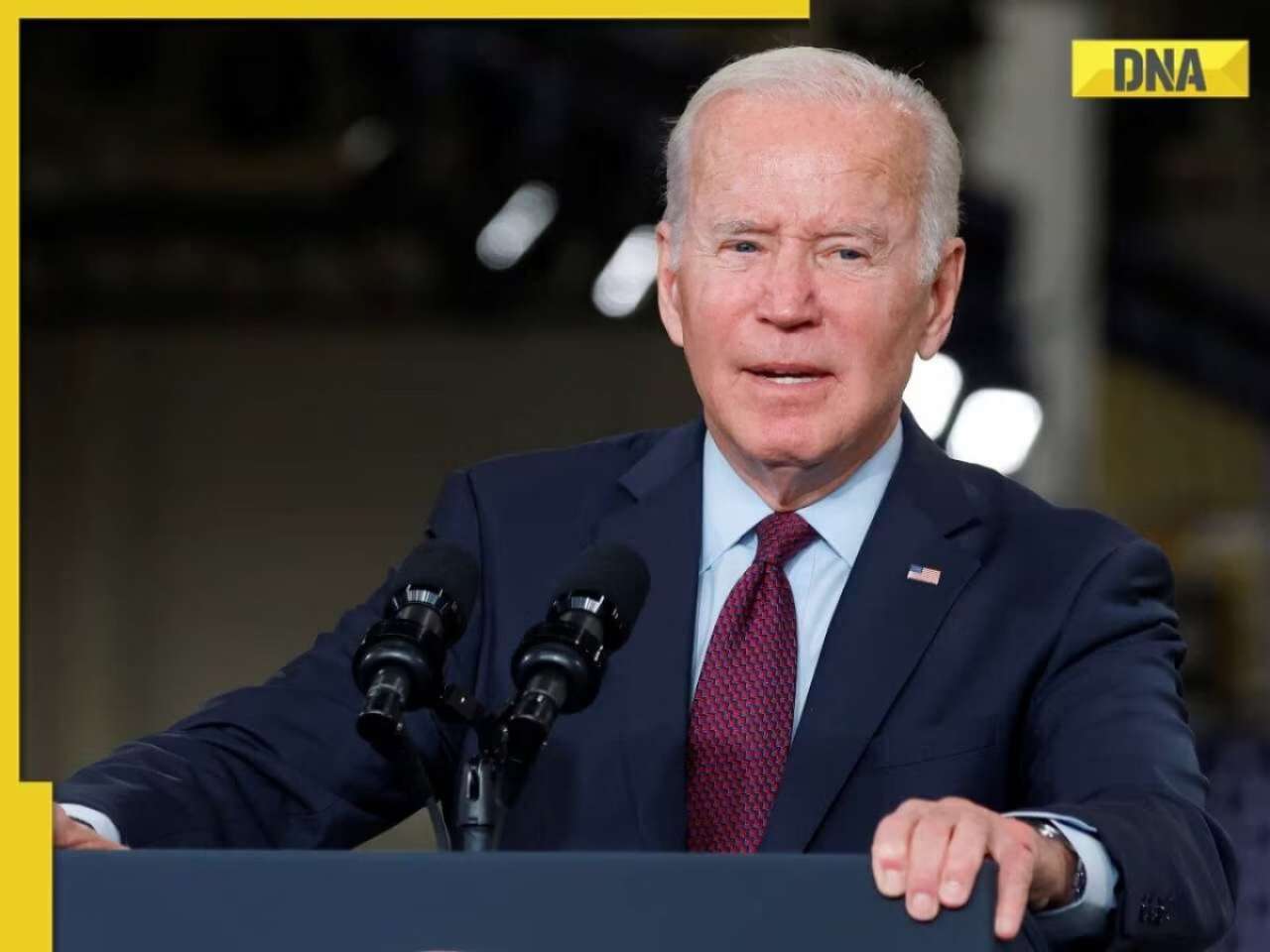

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)