“Our legal system, including the police, is anti-Dalit and anti-poor. The death penalty laws’ wrathful majesty, in blood-shot equality, deals the fatal blow on the poor not the rich, the pariah not the brahmin, the black not the white, the underdog not the top dog, the dissenter not the conformist. . . The law barks at all but bites only the poor, the powerless, the illiterate, the ignorant.”

VR Krishna Iyer, former Supreme Court judge, at the International Conference Against Death Sentence in Stockholm, 1976 (as quoted in Outlook India)

“Is it not laughable that we believe in a sacred, infrangible law, thou shalt not lie, thou shalt not kill, in an existence characterised by perpetual lying and perpetual murder?”— Albert Camus

A country’s reputation depends primarily on the state of its judiciary. Investors too trust a country with good courts.

Last week, the government announced a ban on unlicensed cab services. The ban was absurd, even hilarious. If a licensed sector has an unlicensed operator, is a ban really needed? Ironically, there is a morbid fondness for bans. When there is a problem ban something. The government, at times, bans books, movies, plays and now even cab services. Somehow, the sagacity to deal with them legally appears to be missing among India’s lawmakers and its enforcers.

Move ahead to the case of a famous club in Bangalore which recently suspended a member for unbecoming behaviour. Unfortunately, the suspended member was a law enforcement official. Promptly, almost by curious coincidence, the club was raided for operating a bar without proper licences. If so, how did the law enforcement officer agree to become a member in the first place? Couldn’t that itself be an act of collusion? Could that explain why most clubs give automatic membership to senior government and law enforcement officials?

Then look at instances where the accused — invariably privileged — being freed just because the charge sheet was filed too late, or because the identification parade was not held properly. Consider also how easily privileged jailbirds get paroles compared to common prisoners.

Clearly, despite its veneer of becoming a global player, India’s law making, enforcement and adjudication processes are sorely in need for an overhaul.

The courts hold the key

Crucial to all such cases is the role of the judiciary. It is the only body that can reject a lawmaker’s proposed legislation on the grounds that it violates rights guaranteed under the Constitution. It can even ask the government to penalise a policeman for not registering a case, or for preparing a charge sheet full of holes, aimed to allow an accused to go scot free. It is also the only arm of the government that can demand to know why it took so long for a charge sheet to be filed, and also on the credibility of new evidence that “emerges”. It can also decide when adjournments can be considered as being vexatious.

But the judiciary has not done this. This is partly because it has itself been the victim of political pressure on the one hand, and the lure of temptations on the other.

The political pressure has manifested itself in the form of postings, promotions, post-retirement benefits, travel perquisites and other benefits for the relatives of the select law officers. Conversely, not all the posts of judges are filled up in time. That causes the backlog of cases to become longer. This ensures further delay in the dispensation of justice. And as any lawyer will tell you, delay is always a friend of the accused.

Then there is the delay in creating more courtrooms and support staff for judges; and the refusal to ensure that senior judges get paid a lot more than even the chief executive of any bank. A decent pay package does several things — it shields the person from the temptations held out by litigants and/or their lawyers. But, most importantly, it allows for the best talent to seek out senior positions with the judiciary, thus allowing adjudication processes the benefit of skills and vision.

Judicial reforms are thus the most crucial of all reform. They can usher in more credibility for India as an investment destination, where doing business is relatively safe.

Judicial relevance

Nothing hurts an economy more than the perception that its laws are not reliable. Nothing hurts a bank more severely than the realisation that loans that it had given out have turned bad. Banks are sorely wounded when the courts subsequently prevent them from taking over the collateral for unpaid loans.

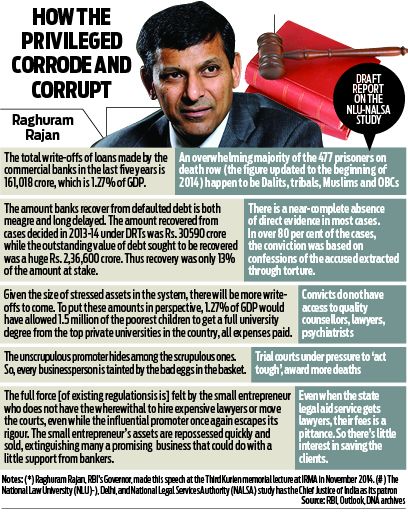

That is why, the remarks given alongside, made by Raghuram Rajan, RBI governor at the Third Verghese Kurien Memorial Lecture at IRMA in Gujarat, are extremely relevant.

Ditto for the findings of the people behind the NLU-NALSA report, backed by the Supreme Court. Both point to the corrosion of values, systems and institutions by the privileged in India. They underscore why criminalisation of politics cannot be eradicated easily unless judicial reforms are introduced. They also painfully point to the need of a judiciary that can move faster, with better understanding of the commercial and social underpinnings that guarantee fair play.

Unless that is done, India will remain an unsafe place — both for the underprivileged in society, and the underprivileged in business, including banking.

The author is a consulting editor with dna