Javed Iqbal recounts what it is like to venture into Dantewada to record the violence and pathos there.

Tarun Sehrawat, a young Tehelka photographer succumbed on Friday to illness — malaria, jaundice and typhoid — contracted during a foray into Abhuj Marh in Chattisgarh. Javed Iqbal recounts what it is like to venture into Dantewada to record the violence and pathos there.

I first met Tarun Sehrawat and the intrepid Tusha Mittal in January 2010, when we found ourselves with the same duties — of trying to investigate why the state of Chhattisgarh had kidnapped Sodi Sambo, a Supreme Court petitioner, and a woman who was shot in her leg during the combing operation of Gompad that took nine lives. She was in a Jagdalpur hospital, and we were outside her ward trying to get access to her. Tusha Mittal would harangue every stubborn official with such gusto, that you were certain that war reporting was best left to women. Tarun and myself sat quietly, joking and taking photographs of one another while Tusha did her job. He had no malice and insecurity that most photographers had for their own. And his innocence was something that you were very glad you could find in a place like Dantewada.

The next time we met, we found ourselves on the way to the villages of Tadmetla, Timmapuram and Morpalli. These were which was burnt down by the security forces in March of 2011. Tusha and I were this time at each other’s necks like a bunch of Laurel-and-Hardy’s on steroids, regarding the best way to deal with the logistics of going into ‘the jungle’. Tarun, as usual would smile to placate our anger at ourselves. We all did do our jobs eventually, and Tarun’s images were an absolute justification of our profession.

Tarun was a witness to our state’s grand security operations in Central India. He has photographs of burnt homes, of widows whose husbands were killed by the security forces, of women raped by security forces, of fragile old men with country rifles who the state refers to as the greatest internal security threat, and of Abhuj Marh, his final assignment, where few have ventured. But one of his most heartbreaking images would remain a photograph of a family in Dantewada sifting through their burned rice trying to separate the ash from what they could eat. That’s what he witnessed. That’s what only a handful of people from the outside world have ventured in to see, including some of the bravest and most brilliant journalists and photographers I have had the honour to work with.

Yet it’s death from Dantewada that follows you around, as with each story of encounters, and killings. Just a few months ago, the controversial superintendent of police Rahul Sharma took his revolver and shot himself. Assistant Superintendent of Police, Rajesh Pawar who I confronted about a fake encounter was gunned down by the Maoists some years later. And now a tortured adivasi journalist Lingaram Kodopi wishes to die in jail, as there’s no way he feels he can get justice in this country. Each name is jotted down in my collection of notebooks, of those killed, of sons named along with their fathers — Madvi Kesa s/o Bhima, Madkam Deva s/o Bhima, Madkam Admaiah s/o Maasa, and countless others. But sometimes I don’t know whether that list will have any meaning, when all that tends to happen, is that the war goes on.

A cellphone becomes the purveyor of madness and death. ‘There’s been an attack in your favourite village’ an activist once called and told me, and I went into a daze, and hated him — how many favourite villages did I have? Then came the final message about Tarun — ‘Pronounced brain dead.’ And this just a few days after friends had told me that he was making a full recovery.

We all think we’re invincible. We venture into roads that could be mined with IEDs, one of which exploded a day after two of us passed, killing three security personnel. We venture into the haven of the malarial monster, the killer of people that doesn’t discriminate like we do. In Basaguda, I remember the sight of a CRPF jawaan holding the hand of another jawaan, whose body was sapped of energy, eyes bereft of life, who would say the dreaded word: malaria. It was an absolutely tragic sight to watch these two towering men, pathetically broken down. “You don’t even have to ask about the mosquitoes. Around 80% of us suffer from malaria at some point or the other.” But mosquitoes have also killed one of the Maoists’ iconic leaders: Anuradha Ghandy. And for the ordinary adivasis, their stories are left to statistics, sometimes to a world beyond statistics.

In Jharkhand, an old adivasi miner who was left to die of asbestos exposure spoke to me, while three young children, slept behind him. All three had high fever. All three had malaria. In fact, a few months into the job, it became standard operating procedure to not just document the atrocities committed on a whole people, but to finally ask about illnesses in the village. At one visit to an IDP settlement at Warangal last year, our investigation team became a medical team, and we had to take on the responsibility of taking people to the nearest clinic.

Some quarters mention how Tehelka should’ve guided Tarun with some precautionary measures but unfortunately those are never enough and some circumstances can’t be helped. Tarun had no option but to drink pond water, in a place where water, even after boiling, would turn yellow. A few years ago, my adivasi guides, a few other journalists and I faced a similar problem. And we had to walk over 15 kilometres of hillocks in a summer that can blaze to 48 degrees, and our water supply ran out. We had to drink from a miasmic river. And we all did and we were lucky.

I used to take anti-malaria pills every week in my first forays into Central India, but still ended up in the middle of nowhere with high fever, huddled up in a bus station, alone and wrapped in a shawl, shivering like my bones would shatter, with my mind drifting away, waiting for a family friend to come and save my life. And I was lucky. Malaria was bombed out of my system. To most people in Central India, there’s no rescue. Where Tarun had gone, no doctors venture. In fact, in some of the areas in Dantewada and Bijapur where Doctors Without Borders did go to work, they were accused by the state of Chhattisgarh of ‘helping the Naxalites’.

The angel of death of Bastar, made of iron ore, is touching and destroying everything that is beautiful. Tarun had a long way to go. Twenty three, the age of most SPOs and Maoists, is not the age to die.

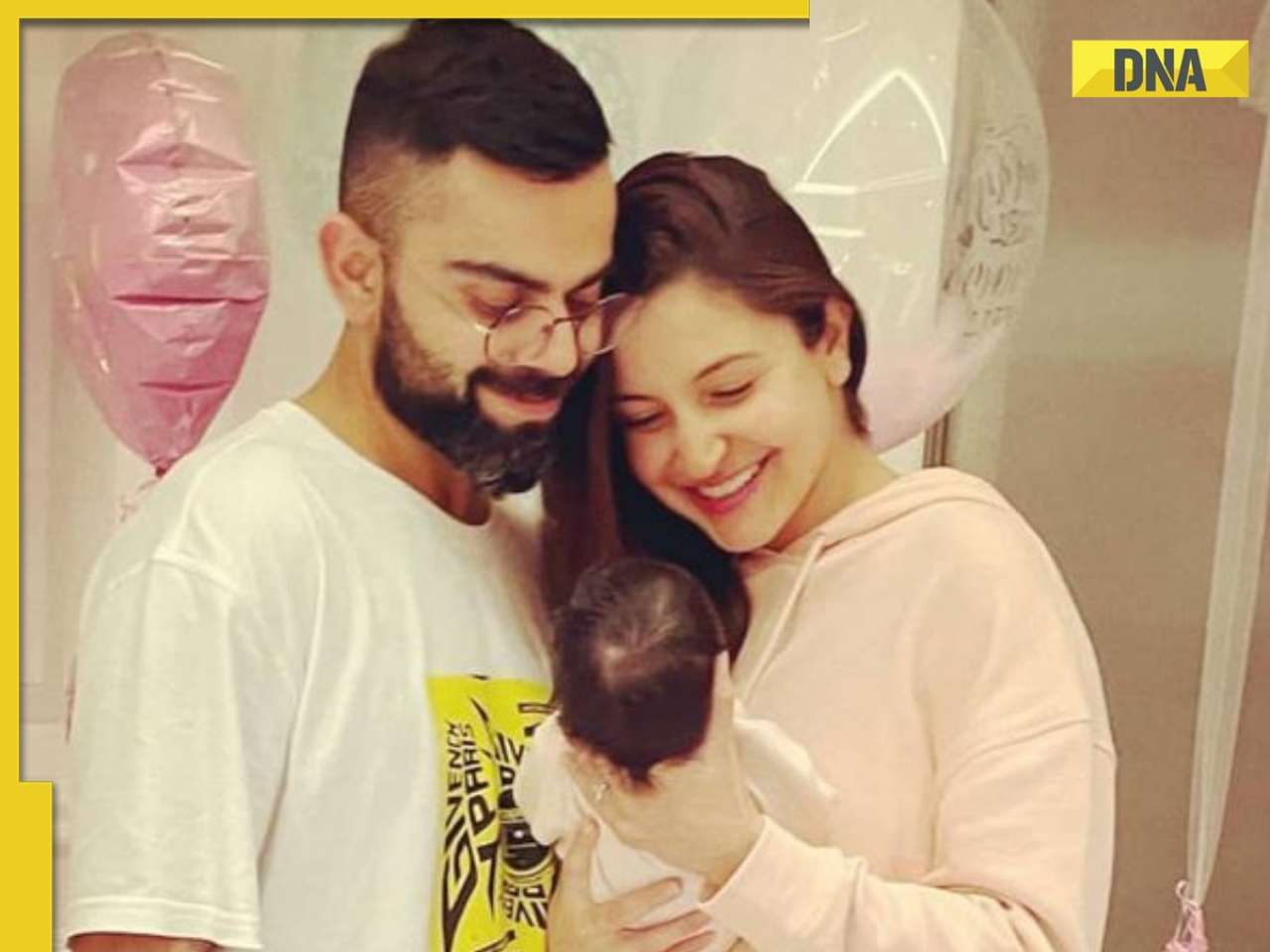

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

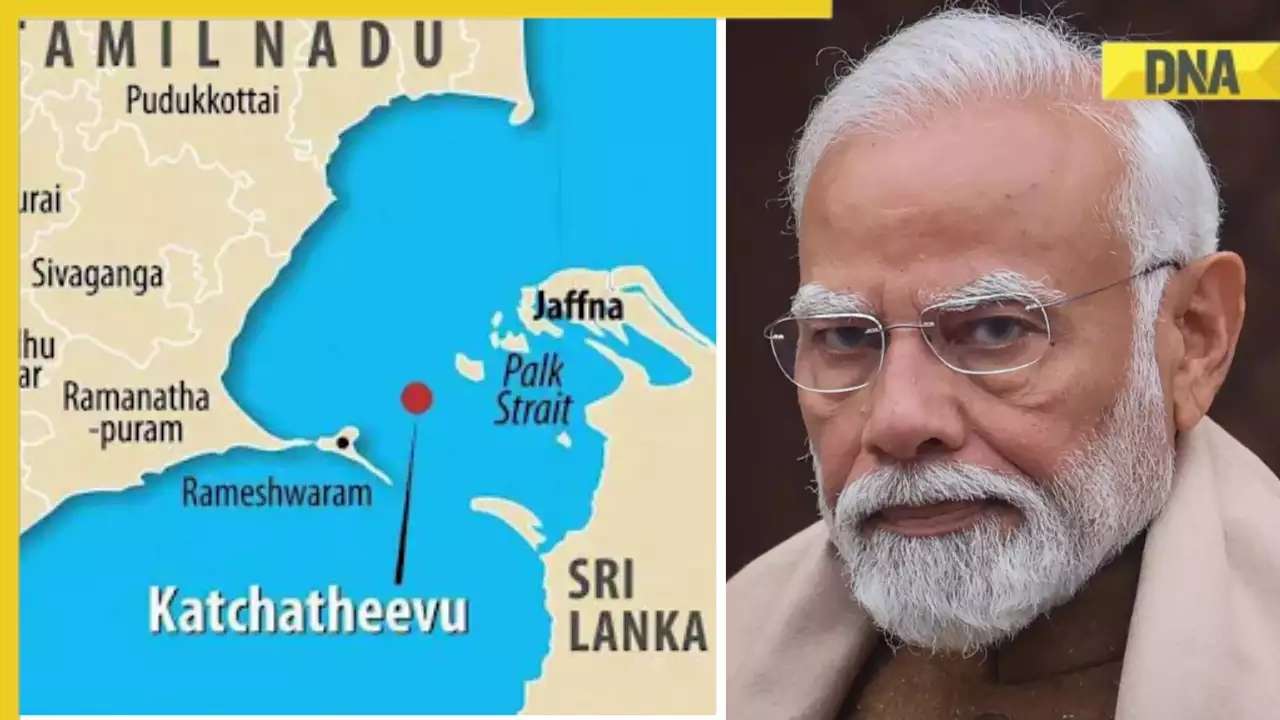

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)