Attakkalari, an organisation he set up in 1992, approaches dance as an inward journey where every turn holds rich sensory experiences, reports Malavika Velayanikal.

The floor was lit. The dancers were practising their moves, body glistening under spotlights, torso drawing curves, limbs snaking and undulating. Fifty two-year-old Jayachandran Palazhy aka Jay was watching them as he put on his socks — an utterly insignificant move if not for the way he did it. Eyes on the dance floor, spine at ease, one leg firm on the ground, the other rose up to reach his hands. It would seem bizarre to believe that a mundane act, one he wasn’t even aware of performing, could describe the sensory experience of Attakkalari. Yet, the fluid grace with which Jay donned his socks underlined his mastery over his body. His hand pointed towards a corner; his eyes followed; in a flash, he seemed to fly across the room. A ripple that began in the curl of a finger went to his toe, and ended in me. Hypnotic, he flowed like synchronised poetry.

...

Little Jay had it tough. His was a matriarchal family in Thrissur. Temple ponds, banyan trees, swings, his mother and friends dancing in graceful circles — dance came to him very early. There were frequent performances at the public spaces near home. Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi and Mohiniyattam. He would watch them wide-eyed. But a boy, growing up in small town Kerala, he wasn’t expected to dance. Let alone take it up as a profession.

Perhaps it was Kathakali that tipped the scales for him.

Traditionally, Kathakali performances happen at night and end early morning. The dancers perform on a stage lit solely by the kalivilaku (a tall lamp), whose wick would flicker in the breeze and create dramatic shadows. Fierce colours, elaborate costumes, haunting music, rhythmic dancing, where the dancers, playing larger-than-life characters, used their eyes, face and hands to tell a tale. You watched it late into the night, sleep-deprived, semi-conscious, and that is when Kathakali becomes magical realism. It’s a heady concoction, totally addictive. Jay came back home, and spent hours imitating the moves in front of the mirror. He was hooked.

“But I had to wait to learn dance.”

The early years

After school, Jay won the national merit scholarship, and took up Physics in college. A class topper, he was into sports — athletics, badminton, cricket — and began Bharathanatyam lessons with well known guru Kalamandalam Kshemavathi. Soon he rebelled, missed a few exams, and lost his scholarship. “I was more interested in dance, cinema and drama. But I completed graduation, and left for Chennai.” He was looking for a guru. “I didn’t know anyone in the city. My teacher Kshemavathi had mentioned a few names, and I wandered around trying to find them.” He finally came to Dhananjayan. “Dhananjayan master was the perfect role model of a male dancer. I was lucky to have learnt under him.”

Besides Bharathanatyam, Jay learnt Kalaripayattu, and Kathakali. When he wasn’t studying, he was teaching. That went on till lunch time. Evenings were spent at the Adyar Kalakshetra. “I became a member of the film club, so watched a lot of Indian and global cinema. And read voraciously — Malayalam poetry, Greek classics, Calvino, Kundera, Neruda… I realised that the magic of Marquez’ stories was what I had experienced during the all-night-long Kathakali and Koodiyattam performances long ago.” All what he read, saw and experienced, together helped “formulate my vision of performance arts”.

The vocabulary, structure and scientific body movements of the Indian classical dances were beautiful. But the context, somehow, didn’t sit right with Jay. “I felt a lack of authenticity. The filmmakers and writers I read had found their language, and I wanted a language too.”

Around 1985, in Chennai’s Music Academy, Jay saw a production by the legendary choreographer Merce Cunningham. “I remember I was fascinated but couldn’t completely understand it. I was still pondering over it when a few friends from London visited Dhananjayan’s dance school, where I used to teach. The director of Middlesex University was among them. He saw me perform, and told me to study dance in London.”

Jay went to the London School of Contemporary Dance in 1987. Ballet, stagecraft, anatomy, music, art history… he studied various subjects. This move also gave him an objective perspective on the dance scene in India. “I could look at it from a little distance and saw that contemporary dance needs an enabling force in India.”

The seed for Attakkalari was thus sown.

Setting up Attakkalari

He set up the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts in Bangalore in 1992. His role was of a facilitator. “Learning cannot come from one teacher. You need multiple possibilities, wide exposure.” As the artistic director of Attakkalari, he wanted to provide that range of possibilities to the younger generation of dancers. “My aim is to bring different knowledge streams together, so that we would have a thriving contemporary dance scene here,” he explains.

In the beginning, Attakkalari was about a fluid group of poets, thinkers, filmmakers, theatre people, choreographers, dancers and visual artists who came together to discuss ideas for contemporary expressions. Jay was still working in London, and making frequent visits to host these creative discussions. In 2000, when Sri Ratan Tata Trust awarded him the corpus fund to start the work, he moved to Bangalore. “The space got ready in 2001, we were on.”

Does contemporary dance — ‘body movement’ as Jay likes to call it — stand in conflict with the classical dance forms? “Of course not. I admire all the classical forms, they are a valuable reservoir of traditional knowledge. But as a society, if we do not create new languages, the traditional knowledge system would simply get fossilised. Only if we have contemporary dance forms along with classical dance and an equally vibrant folk tradition can we claim to have a rich art scene.” It is when we make it ritualistic that it would spell trouble, he clarifies.

So what is Attakkalari now? Its mission is to spread the reach of contemporary performance arts. It makes dance a viable career option for young people. It has a Repertory Dance Company, which has been performing full-length, multimedia dance productions, choreographed by Jay. Their latest production, Meidhwani (Echoes of the Body), will be performed today at the Seoul International Dance Festival.

Attakkalari offers a diploma in movement arts and mixed media, an intensive one-year programme. The applicants are screened through auditions held in multiple cities. “We pick 20-25 students. The selection is thorough because this is no jolly course. About 15 students last till graduation,” says Eliam Rao, in-charge of the education and development wing. “It is tough, unbelievably tough,” she adds. Twenty six-year-old Keya Ann D’Souza agrees. She is a dancer from Mumbai, who enrolled for the programme to better her skills. “Well, to say the least, it transformed me. It gave a whole new perspective, and taught me a new vocabulary,” she says.

Attakkalari also has community outreach programmes, and conducts regular classes in contemporary dance, classical dance and Kalarippayattu for the public across all ages at their studios in Bangalore. They organise different modules for schools and corporate organisations as well.

Sums up Jay, “As dancers, if we are to make sense of our lives now, we need new languages.”

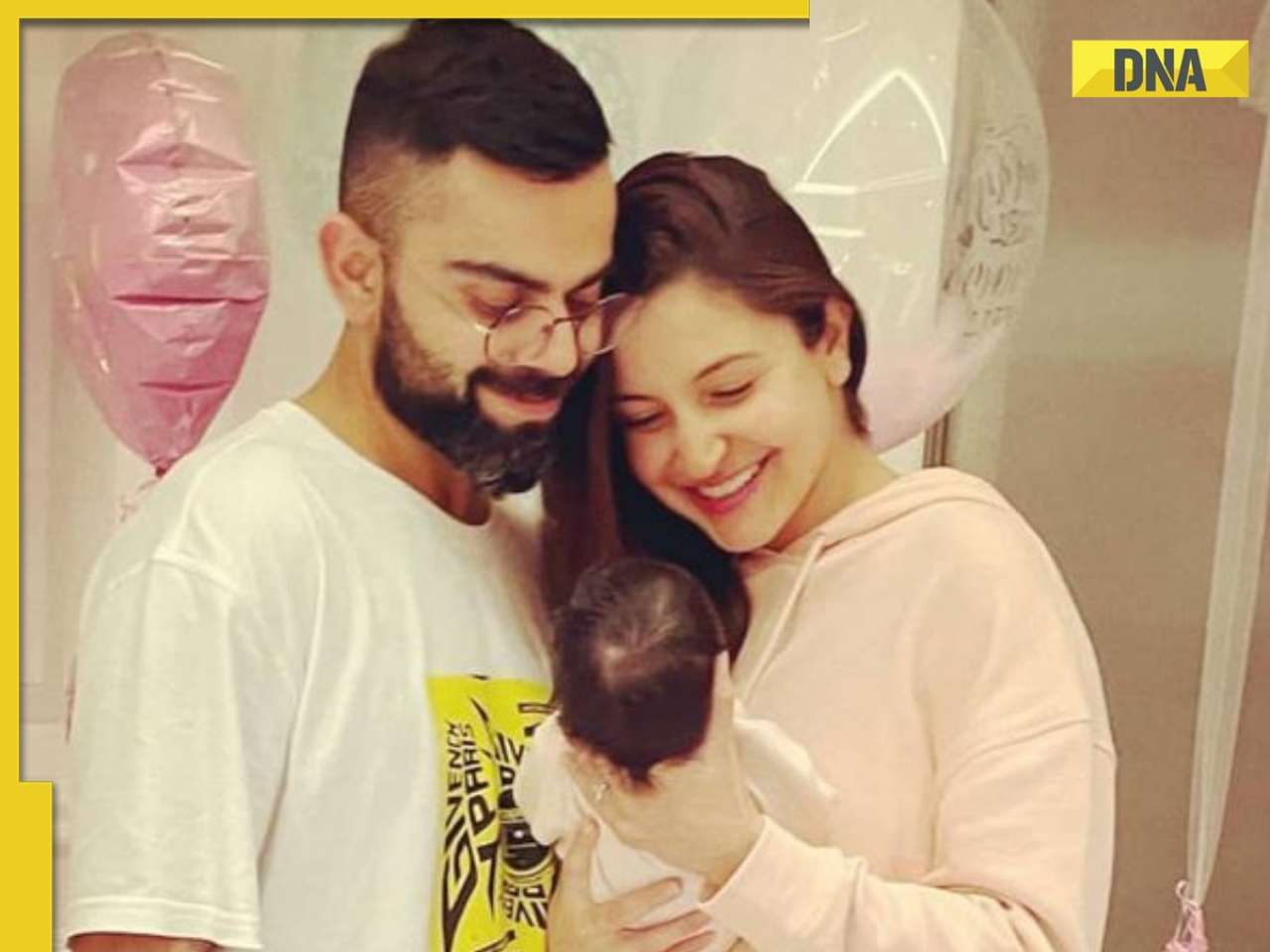

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

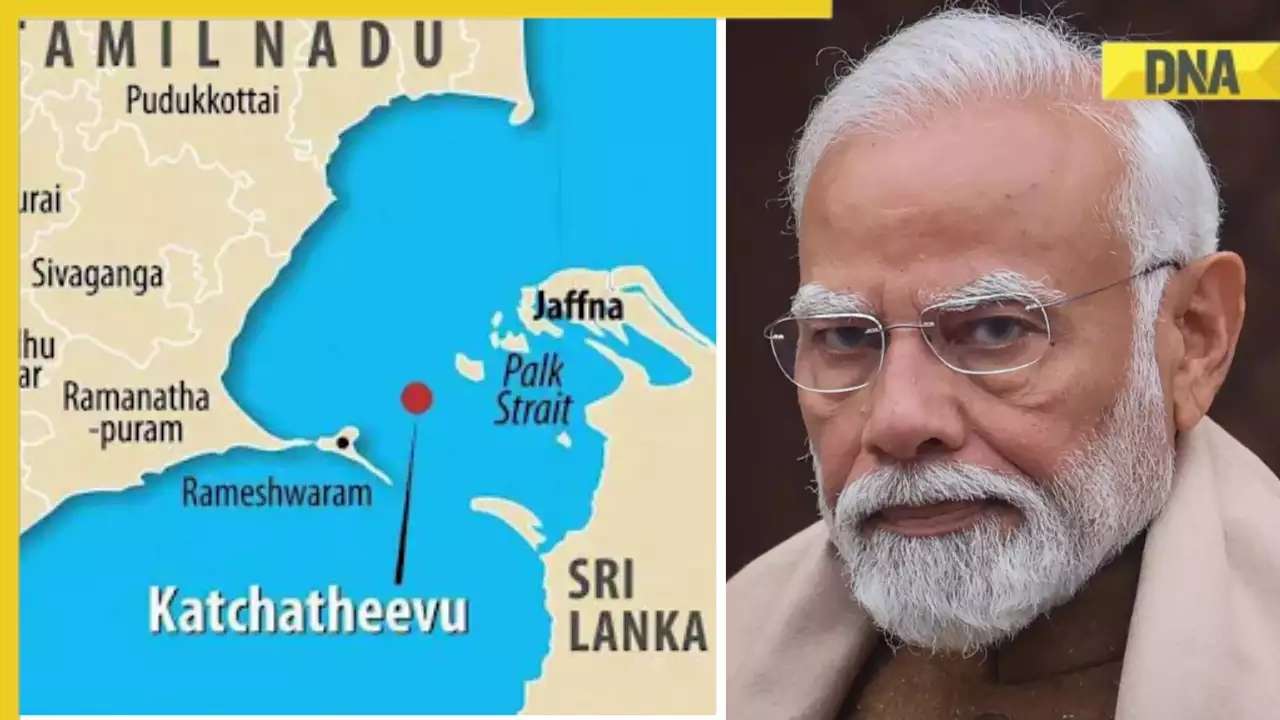

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)