Populating Dudhwa, a national park in UP, with the one-horned rhinoceros from Assam, has turned out to be one of the best examples of relocation of an endangered species, writes Gangadharan Menon.

After the last rhino was shot dead by a European hunter in 1878, Dudhwa didn’t have a single rhino for over 100 years. Then, in April 1984, five rhinos were brought in from Kaziranga in Assam, and later, five more from Chitwan in Nepal.

Today, three generations of the Great One-horned Rhinoceros roam the grasslands of Dudhwa, and their number is a healthy 31.

Unlike tigers, whose footprint is spread across India, rhinos could only be found along the Brahmaputra valley in northern Assam and West Bengal. And of the entire population of rhinos, 70% are in one sanctuary: Kaziranga.

Now we were on our way to the only other place which harbours the one-horned rhino, thanks to their relocation. The Terai region in UP used to be a stunningly beautiful mosaic of blue and green: rivers, swamps, lakes, grasslands and dense Sal forests. But over a period of time, poachers and the timber mafia have left their mark.

We first passed through the Kishanpur Wildlife Sanctuary outside Dudhwa, which was slushy with unseasonal rains. There, we saw an old rhino that had wandered across from Nepal, maybe pushed out from the herd that he once ruled. “There are no other rhinos here,” said Sonu, our guide. Gazing at the forlorn rhino, he continued, “Saab, Kishanpur is completely cut off from Dudhwa. So even if this rhino attempts to get to where the other rhinos are, he would get poached on the way. His days are numbered.”

Saviour of Dudhwa

Dudhwa, where we went the next day, was established as a national park for protecting deer in 1977, as half of the world’s critically- endangered deer population lives here. It is the only sanctuary where five different species of deer co-exist. Sadly, their numbers have decreased over the years – a decade back, there were herds of 100; now, they barely touch 40. And once you lose deer, you lose the tiger.

Dudhwa, like the rhinos it now harbours, has had a second wind, however, thanks to the efforts of one of the most controversial figures in Indian conservation, Billy Arjan Singh.

Billy was a hunter who had a change of heart after he looked into the eyes of a leopard he had killed. Just as non-believers become fanatics after they turn believers, hunters too become passionate about conservation after they are converted. Almost single-handedly, Billy fought for the protection of this unique forest and all that dwelt in it, which led to several run-ins with the powers that be.

He became controversial for introducing hand-reared leopards and tigers back into the wild, though his experiments were invariably successful. His film, The Leopard that Changed its Spots, is a wonderful account of how he re-introduced a leopardess named Harriet into the forests of Dudhwa. Billy also took a tiger named Tara back to the wild. He would train these predators to hunt under supervision, before releasing them into their natural habitat, where only the fittest survive.

Setting an example

“Don’t look for the tiger,” Manoj Sharma, an expert naturalist, admonished us as we went trekking into the forest, “because if you do, chances are you will miss a hundred other species: birds, insects, animals, trees and flowers.”

The Sal tree, for instance, harbours lakhs of termites in its deep ridges, and these in turn attract a host of woodpeckers — seven different species in all. In fact, this sanctuary is also a bird-watchers’ paradise: of the 400 species of birds found here, we counted as many as 96 in just two days.

Finally, on an elephant-ride through a forest path in Dudhwa, lush with grass as tall as the elephant itself, we chanced upon what we had come to see. It was a rhino with a new-born calf. We left feeling convinced that all was well with the relocated rhinos here.

In Dudhwa, the rhinos are in an enclosure spanning hectares of grasslands, a replica of the rhino habitat you find in Kaziranga and Manas.

This is well-guarded, for rhinos are a prime target of poachers for their prized horns. Visitors too are allowed only sparingly, only on elephant-back in the buffer areas. The rhinos now feel at home in this habitat which has been preserved for decadeswithout human encroachment.

Despite the example of Dudhwa, however, relocation continues to be vehemently opposed by conservationists. The Gujarat government has refused to allow translocation of the endangered Asiatic Lions to Madhya Pradesh, on the grounds that MP doesn’t have enough of a prey-base for the lions, or protection from poachers. Is this because of a genuine environmental concern for lions, or fear of losing Gujarat’s Pride, I wonder.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

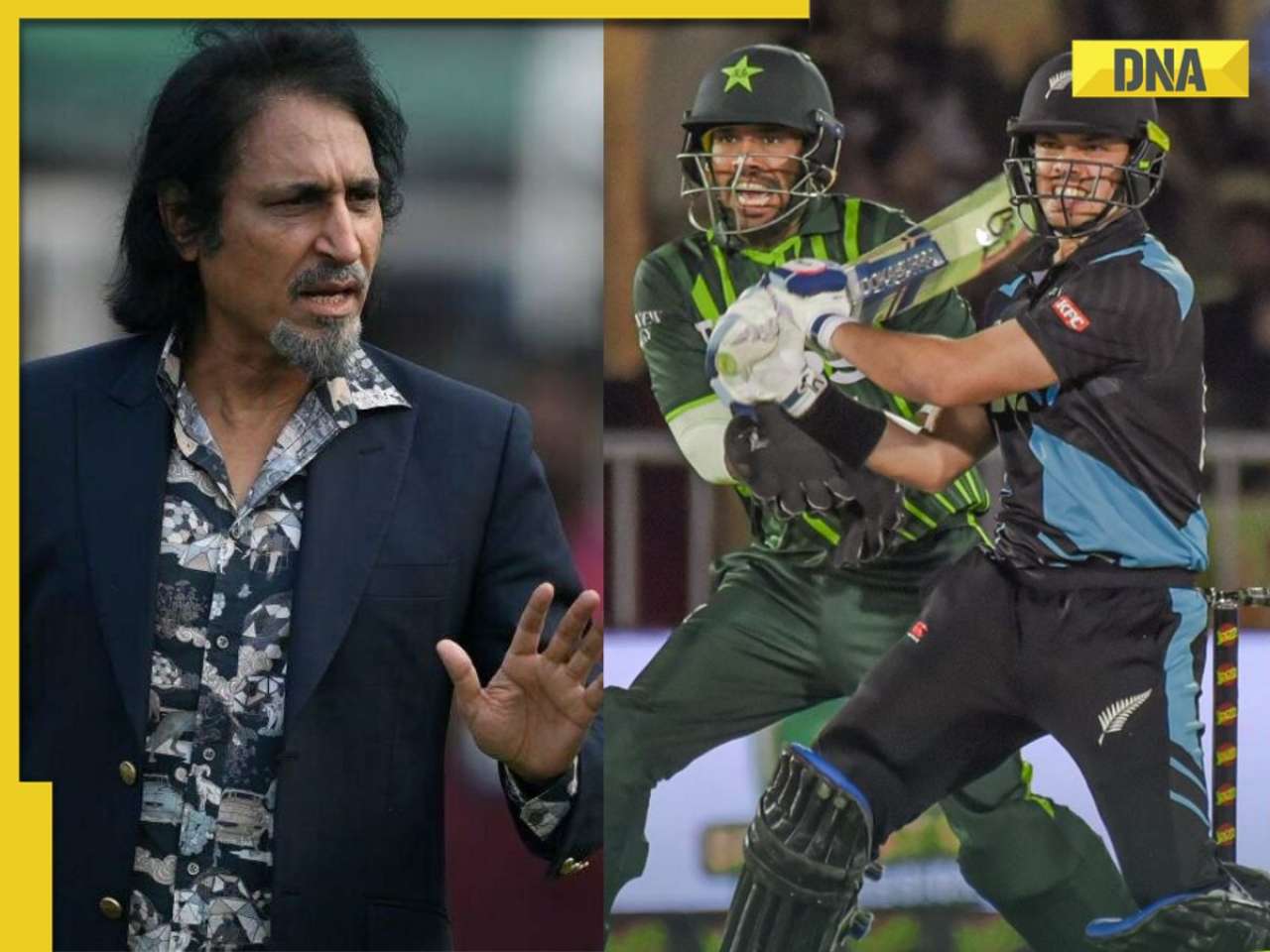

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

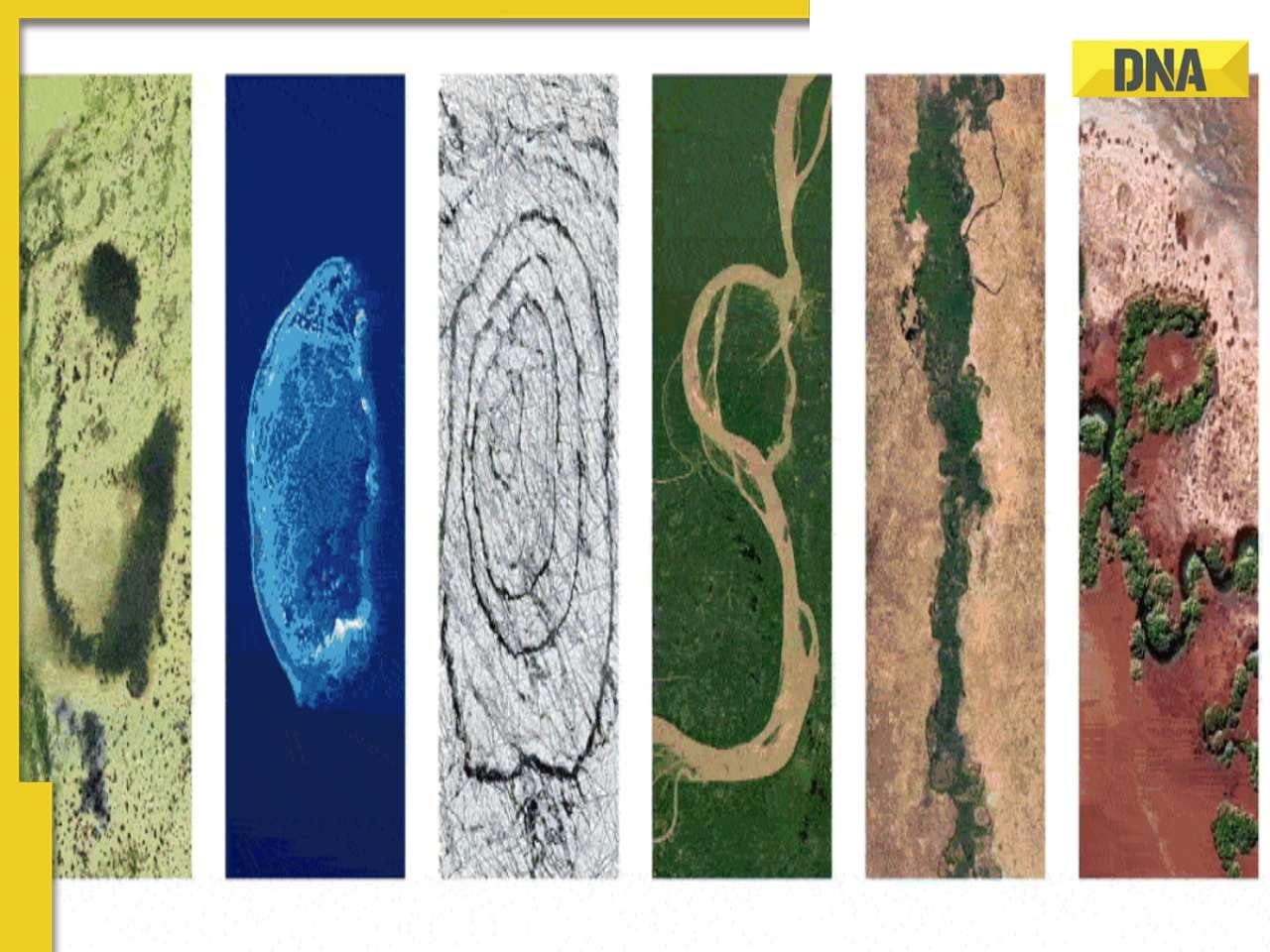

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)