Fashion makes us other people; fashion retail turns old spaces into someone new. Pockets of cities have rejuvenated and gentrified by waves of fashion retail. Over the past three years, south Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda has shed its stodgy blue-collar all-weather office wear to open the store windows to Masaba’s vociferous prints, Nicobar’s Indo-urban daily wear, Manish Arora’s unmissable sartorial screams and Gaurav Gupta’s molten gold sari-lehenga fantasies (which replaced Sabysachi’s subversive nostalgia).

Fashion makes us other people; fashion retail turns old spaces into someone new. Pockets of cities have rejuvenated and gentrified by waves of fashion retail. Over the past three years, south Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda has shed its stodgy blue-collar all-weather office wear to open the store windows to Masaba’s vociferous prints, Nicobar’s Indo-urban daily wear, Manish Arora’s unmissable sartorial screams and Gaurav Gupta’s molten gold sari-lehenga fantasies (which replaced Sabysachi’s subversive nostalgia).

Once, the area was allegedly quasi rent controlled due to ancient rent agreements, but after fashion glossed it over, the rents have allegedly sky-rocketed. According to one press report, designer Gaurav Gupta allegedly rents the ground floor property opposite the Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue for Rs five lakh a month.

The Fort area is expected to undergo a similar transformation after its recent fashion transfusion via Zara. The Spanish high street brand has spread itself languidly over 50,000 sq ft and five floors behind the iconic (even when veiled for renovation) Flora Fountain. The rent at Ismail building? An eye-watering Rs 2.5 crore a month. And with Zara here, can H&M be far behind?

The bylanes branching out from Colaba Causeway have been fashion victims for long, with multi-designer and lifestyle stores such Ogaan, Good Earth, (the now transplanted) Bombay Electric, The Courtyard, Bungalow 8 and designers Payal Khandwala and Arjun Khanna setting up a presence there. In the Capital, after Defence Colony and Haus Khas, Mehrauli, around the historic Qutub Minar, is the new style mile.

So how does a fashion infusion change a neighbourhood? And is the relationship symbiotic or parasitic? Depends on whom you ask.

Artful Symbiosis

A long time ago, designers opened stores solely in the cooled and hallowed halls of five hotels, believing both – that their brands needed to nestle in such rarefied air and that this was where their clientele clinked champagne flutes, and would, by happenstance, buy a handbag or skirt for a bejewelled evening.

Independent mid-level designers would also camp in garage spaces of the wealthy or in stores made feasible by ancient rent-controlled agreements. When India’s fashion scene became an organised industry in the 1990s, designers started seeking neighbourhoods or structures that echo their brand’s aesthetics. Ensemble started off, and remains at, Lion’s Gate in Colaba.

Similarly, artist-turned-designer Payal Khandwala’s first stand alone store came up at Apollo Bunder Road on the far side of Colaba in 2014. The area was in the middle of its second fashion gentrification swing. In 2008, Maithili Ahluwalia’s Bungalow 8 had taken over three floors in the same Grants Building as Wankhede Stadium (and their permanent store in it) underwent renovation. The Courtyard – a complex at Apollo Bunder housing Amrapali, Abraham & Thakore, Tulsi, Rajesh Pratap Singh – was hanging by it last thread. Khandwala took over the bottom space Bungalow 8 used.

“We were drawn to it’s unused, neglected look. We liked that it had a patina to it. The streets below are Little Arabia,” says Ahluwalia, referring to the ittar and hijabi fashion stores catering to Arab tourists. “It looked like a place about to implode or explode,” she adds. They restored the glory of an old staircase, polished the old electrical switchbox so that it shone as much as any piece of art.” They hoped to co-exist with the old bread shop and the Chinese family-run beauty parlour below.

Khandwala was drawn to the same outer and inner aesthetic sensibilities that established her first-floor store. “Colaba itself has a lovely character,” says Khandwala. “The arched windows and the exposed rafters on the ceiling were loveable characteristics of the 150-year-old building. We weren’t too fussy about a ground floor space since we didn’t expects buyers to stumble in through the door.” Khandwala works with rich, jewel-toned woven fabrics falling into deceptively simple silhouettes that stop short of couture, but are not daily pret. They are a glamazon’s version of Smart Formals, and not likely to be the kind of things you’d pick on a boring, rainy Sunday afternoon.

When time came for her to open another store, this time in the city’s western suburbs, she couldn’t find anything at Linking Road, Turner Road or Juhu Tara Link Road – the established arteries of fashion retail. “They were frightfully expensive and too shop-like,” she says. She finally found a niche in Chimbai village, wedged between two certainties of that shipping village’s life – Dr Hingorani and Pinky Wine Shop. She is the only fashion/ design presence there, renting space in the Chimbaikar bungalow. “There’s a cemetery close-by, quiet walkways and Sanchin Tendulkar lives down the road,” says Khandwala, who was introduced to the place by fellow artist Reena Kallat who would rent a studio there.

Given the geography of the place, it’s unlikely to develop into a fashion hub, and joining the flowing current of local life is the direction Khandwala wanted to swim in.

Capital designs

Anita Dongre looks for places that can be transformed into a haveli in Rajasthan – the state her brand draws constant creative sustenance from. “Location plays a vital role in luxury shopping,” says Dongre, whose empire encases AND (western wear), Global Desi (boho-chic), Grassroot (eco-conscious pret), Anita Dongre (bespoke bridal and couture) and Pink City (handcrafted gold jewellery). “I must be able to visualise how to recreate the interiors to suit the product).

In 2016, she opened her largest store in what used to be a private residence, diagonally opposite to the Qutub Minar. It spreads over 10,000 sq ft at a rent no one in the industry wants to hint about. Not even Bharati Realty, that owns it. “The location is suitable to a luxury shopping experience,” says Dongre, “I love to go up on the terrace in the dusk, listen to the cacophony of the birds and admire the Qutub.”

Other designers have been quick to bask in the glow of the UNESCO heritage structure, first mined by the eatery Olive (and the Tamarind Court much before that in the last century). Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Rohit Bal, Ogaan, Adarsh, Pallavi Mohan and Carma already exist, and current fashion darling, Rahul Misra is slated to join them next month.

“The charm of the area,” says industry analyst and mentor Ramesh Menon, “is that because the shops lie on the periphery of the heritage area, developers are legally bound to preserve the outer integrity of the structures. The rents are also lesser compared to a mall, though peripherally, everything is taken care of over there.”

The adjoining village of Mehrauli continues to exist and it’s newly rich – harvesting the rent from these commercial spaces – have discovered an appetite for fashion. “Many designers,” says Menon, “have re-oriented their staff to recognise these people in chappals and pajamas as their clients and to address them accordingly.” In plainspeak, to not shoo or talk down to them.

While Mehrauli-residents may be interested in fashion, label consumers may not be interested in Mehrauli, says Shriti K Tyagi, who conducts heritage walking tours under Beyond Bombay. One such is Mapping Mehrauli which stops at the shrine of the 11thcentury sufi saint Qutubuddin Bakhtiya Kaki, the first sufi saint to come to India; and Hijron ka Khanqah, a spiritual retreat for transgenders of the Hijra community.

“We have a historic lethargy,” says Tyagi. “And sometimes, these elements of urbanisation interrupt historical revival instead of rejuvenating it.” She argues that shoppers to the Qutub may bring a foreigner or two alone to bask in the shadow of the minar, but they are unlikely to explore the urban village of Mehrauli on foot. She hasn’t seen increase in curiosity about the area, or even growth in awareness about its cultural wealth. “People are vary of walking to discover dilapitated pockets of heritage,” she says. “Fashion shows could work with history as a backdrop and enhance the heritage.”

Ahluwalia feels that this gentrification is a double-edge word, causing saturation and heightened rents, and finally, desertion. “Retailers forget there is something beautiful about the grit and the glamour. You have to be part of the larger landscape. When too many designers crowd a place, it loses its diversity, and the neighbourhood becomes a pastiche in itself. We were renting space in Colaba at Rs 275 per square foot,” she says, “Then in 2008, the market crashed. Now, they can’t command Rs 125 per sq feet.”

The reason why Ahluwalia holds fast to it their Wankhede stadium place is because the rent agreement, dating to 1968, ensures that no other design space will come up in the area.

When rents rise, independent designers that established the burrough, are forced out and the only takers are international chains with deep pockets. As is the slowly the case with Kala Ghoda.

The Khas effect

And as the cyclic rise and fall of Haus Khas Village’s fashion cred has shown. The original water reservoir that gives Haus Khas its name was built by Allauddin Khilji and restored by Firuz Shah Tuqhlaq, whose tomb later overlooked it. In 2004, Delhi Development Authority channeled Yamuna’s flood waters into it.

Bina Ramani first established the Delhi outpost as a trip worth making with her piquant designer store, Once Upon A Time. This was in 1987 and the rent for the space was Rs 2000 (it’s was fetching Rs 600 as a cowshed). In 1990, it grew a restaurant, Bistro and accumulated the pillars of a chic bohemian neighbourhood — cafes, artist studios, galleries, design stores, bookstores, bakeries and fashion designers. The rents rose, and the villagers prospered. Maruti cars appeared on it narrow roads and backpackers lounged in the cafes.

And then it dried up, as such markets are wont too, and through the late 90s, the Haus Khas was used only for storage and by offices; Ramani left for Goa in 1996. By the mid 2000s, it saw another revival, through like-mind small entrepreneurs. Quaint independent designers (that did not cater to the cash cow wedding trousseau market and advocated a recycling, upcycling, organic or hand-made philosohpy) mushroomed – 11.11, Bodice, Lovebirds that then sourced vintage clothes and The Grey Garden. With it came creperies, vegan cafes, experimental pay-it-forward or pay-as-you-wish cafes, and coffee shops. Ogaan the multi-designer store, for a long time, was the only heavy weight fashion retailer. This time, there was a word for it – hipster.

Soon, the chains wanted came in to monetise on this vibe, and you knew the first nail was in the coffin when Cafe Coffee Day perched its first sun umbrella. Leases, which were first drawn up for two to three years, were now truncated to 11 months, sowing insecurity. In the last two years or so, the neighbourhood has mostly become a night spot with eateries and bars sustained by yuppies. The music is loud, the alcohol expensive and the crowds, disrespectful of the villagers that reside there.

With unsupervised structural modifications (it does not fall under the jurisdiction of Delhi’s Municipal Corporation), it’s poised for another crash, say old timers. The budding designers have moved to Shahpur Jat...

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

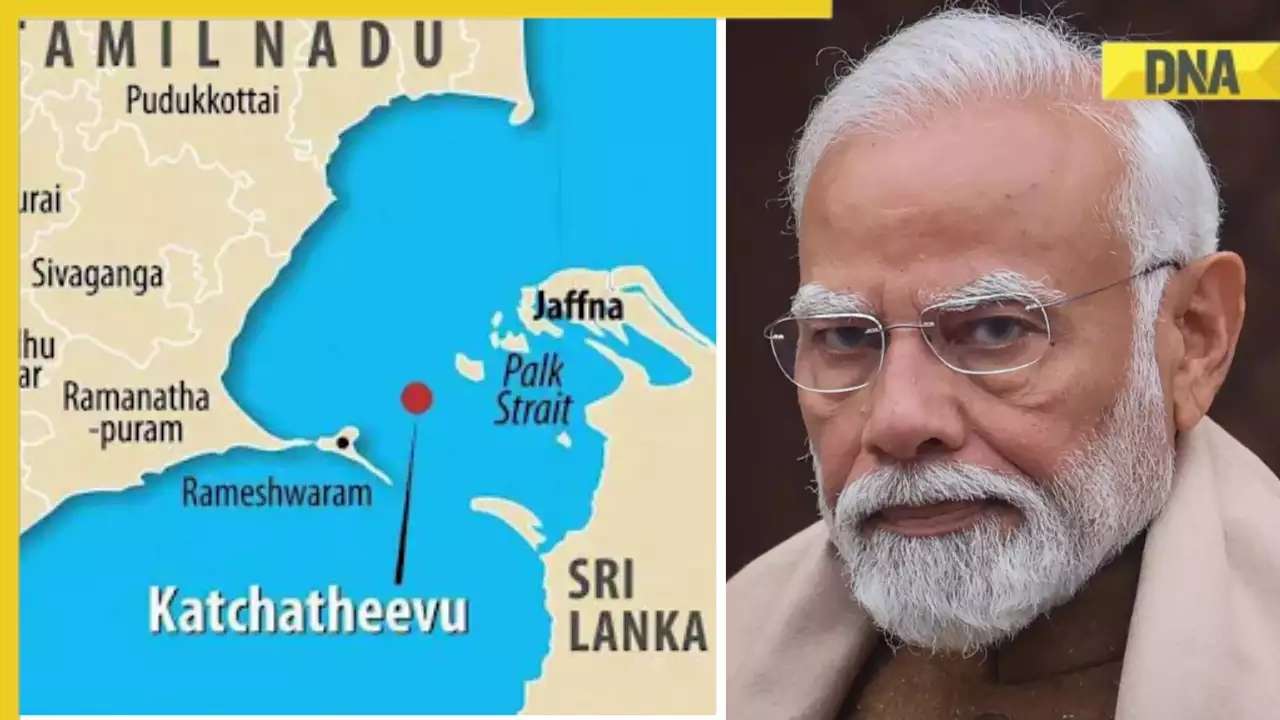

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)