The Drukpa nunnery in Ladakh is home to a self-empowered branch of feminist Buddhism that not only encourages nuns to train in Kung Fu, but also lets them study and seek enlightenment on a par with monks.

The early-morning peace of Ladakh, says Tenzin, a local shopkeeper, is broken every morning by them. I follow the wave of his arm. You would expect perhaps a noisy neighbourhood, a boisterous bunch of hoodlums, or a gaggle of over-enthusiastic tourists. Tenzin is, in fact, waving towards the Buddhist nunnery of His Holiness the Gyalwang Drukpa, a majestic array of buildings with thousands of prayer flags fluttering around it. The culprit?

“The nuns,” he says vehemently.

Every day at 4am in the Drukpa nunnery, the thin, tinny silence of Ladakh is shattered by the shrill haee-yas and huuus of the nuns practicing their kung fu. Over a hundred under-25 Buddhist nuns, far from the fabled birthplaces of kung fu, spring kick and punch into the thin mountain air. They are taught by Jigmet Gendum, a surly Vietnamese monk who barks orders and walks amongst the ranks, straightening legs and correcting postures along the way.

The fact that they are Buddhist nuns — a religion known less for its acceptance of violence and physical combat, and rather more for its relentless misogyny in limiting women to only a certain level of enlightenment, makes these nuns an unusual sight: like something Hollywood might dream up. But the kung fu nuns — as they are known throughout the world — are only the most public manifestation of the Drukpa leader’s attempts at female emancipation.

‘I wanted to be like Jackie Chan’

Migyur Palmo, 20, has been at the Drukpa nunnery for four years. She loves kung fu, Jackie Chan movies, has her own email id, but doesn’t understand the appeal of Facebook. “It’s a waste of time,” she says, crinkling her forehead disapprovingly.

It has taken me an hour to get her to open up: for the first forty minutes, she answered questions with the rehearsed ease of a beauty contestant. Migyur is attractive, well-spoken, and unfailingly devoted to the life she has chosen. No, she never wanted to be anything other than a nun. No, she was never persuaded to become a nun. No, she doesn’t miss her old life. All she wants is enlightenment. So does she want to become a Buddhist guru herself one day? No, no, she corrects me quickly. She means in the next life. In this life, serving the Drukpa and helping people are her goals.

It is when I ask her about kung fu that she opens up. “I saw Jackie Chan movies when I was younger,” she giggles. “I wanted to fight like him, and do all the fancy moves. I love that the most. Of course,” she adds quickly, “Kung fu for us is just exercise, not for fighting. It makes us healthy and we even meditate better.”

She occasionally misses her family, Migyur finally admits. “I can’t leave the nunnery for longer than a week per year. But they had also felt that it was important for every family to have a nun, as a sort of representative.”

Ayee Wangmo, a good friend of Migyur’s, is an 18-year-old nun who ran away from home to the nunnery after the Drukpa gave a speech at her Ladakhi village. “I had never heard anyone talk about such things,” she says wonderingly. “It changed me, from the inside, you know?” Ayee says that in her first year, she was desperately homesick. “I missed my sisters. I would get distracted and my mind would wander. I was too talkative. But the other nuns mentored me.” Ayee concludes, “Coming here was the best decision I ever made.”

‘My father didn’t understand’

Carrie Lee, the president of Live to Love NGO, which works with the Drukpa in the Ladakh region, believes that the Drukpa is not exactly progressive, but in fact, returning Buddhist women to the stature that was given to them many centuries ago. “I call the Drukpa lineage the ‘get-off-your-ass-and-do-something lineage,’” she laughs. “Most Buddhist nuns are treated as servants. At the Drukpa’s nunnery, they consider themselves to be mentally and physically stronger than the men. I remember one occasion when the nuns and monks were on a trek together, and the nuns complained the monks would slow them down as they don’t work as much as the nuns do!”

The Drukpa nunnery might be the only instance in the world where there is a waiting list to get in. Kanchok Wangmo, 19, had to fight her family to come to the nunnery. “I wanted to help people. They told me to stay at home and become a teacher. But anyone can become a teacher, only a few can study under guruji’s tutelage,” she explains. Kanchok, who is from a small Himachal village, is more forthcoming about her transition from layperson to nun. “I was a little disappointed when I came here, because I expected there to be a college,” she says sadly. “But it’s basic education, which I’ve already had.” She talks freely about how her father, a rice farmer, was unable to accept her as a nun and cut off ties with her for two years. “Oh, he just missed me,” she says affectionately. “He didn’t understand.”

Despite the time I had spent with these nuns, I too, didn’t understand. From a city-bred atheist’s point of view, I questioned them persistently: but why? Why, when you could help people as a doctor, a teacher, or as a good mother does? Kanchok answered patiently. “I wanted to be a doctor once, like my elder sister is now. But why fix the body, which only manifests symptoms of the sickness, when you can fix the source of the problem — a fault with the soul?” But you must miss something? Kanchok hesitates, and it is clear she has thought of something, or someone, before she answers: “In this life, we have no money or power. By becoming a nun, I hope to achieve a better spiritual status in my next life [that is, be reborn as a man] and help more people.”

Feminist Buddhism

“Seeing nuns doing kung fu is a beautiful thing,” says His Holiness the Gyalwang Drukpa. “I want to help women, and my own nunnery is the best place to start. I also make sure that I teach texts to the nuns directly. Then, if the monks want to know these teachings, they have to learn from the nuns.” The Drukpa explains that these women have faced a lot of oppression. “They suffered with their families and a backward lifestyle. Now, after centuries, they are being trusted with ancient secrets and texts.”

Many of the nuns who come to the nunnery are orphaned or homeless. But many others have chosen this life, despite having all the opportunities the ‘other’ world had to offer. “One nun used to be a J&K counter-terrorism agent. Another one was a week from leaving for Canada for a marketing job when she joined the Drukpa nunnery,” points out Mary Dorea, a volunteer with Live to Love. “An increasingly self-empowered branch of feminist Buddhism is emerging.”

Chandramouli Basu is the director of the BBC documentary Kung Fu Nuns, and he was in Ladakh to show the film to the Drukpa nunnery on the occasion of the Annual Drukpa Council 2011, a meeting of religious leaders and followers from across the globe. The movie tells the story of Kunzang, a 29-year-old nun, as she and her fellow nuns prepare to perform the ritual of the Dragon Dance, which was previously only meant for monks to perform.

Anxious to prove themselves, the nuns sweat it out in preparation.

“The rapid transformation at the nunnery is inspiring,” says Basu. “Especially seeing it happen against the setting of religion, which is perceived as being the last pillar of conservatism, is a source of hope.”

The film was screened in the same courtyard at the nunnery where the nuns practice their kung fu every morning. Thousands of nuns sat on the stone floor, cross-legged, cheering wildly under the clear, starlit Ladakhi sky, whooping when they recognised a nun on the screen, oohing sympathetically as one broke her ankle during rehearsals. Kanchok, sitting next to me, squeezed my hand happily as the movie ended with the successful performance of the Dragon Dance. “Isn’t it beautiful?”

![submenu-img]() Rakesh Jhunjhunwala’s wife sold 734000 shares of this Tata stock, reduced stake in…

Rakesh Jhunjhunwala’s wife sold 734000 shares of this Tata stock, reduced stake in…![submenu-img]() West Bengal: Ram Navami procession in Murshidabad disrupted by explosion, stone-pelting, BJP reacts

West Bengal: Ram Navami procession in Murshidabad disrupted by explosion, stone-pelting, BJP reacts![submenu-img]() 'We certainly support...': US on Elon Musk's remarks on India's permanent UNSC seat

'We certainly support...': US on Elon Musk's remarks on India's permanent UNSC seat![submenu-img]() Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’

Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore

Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’

Adil Hussain regrets doing Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Kabir Singh, says it makes him feel small: ‘I walked out…’![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore

Deepika Padukone's worst film was delayed for 9 years, panned by critics, called cringefest, still earned Rs 400 crore![submenu-img]() India's first female villain was called Pak spy; married at 14, became mother at 16, left family to run away with star

India's first female villain was called Pak spy; married at 14, became mother at 16, left family to run away with star![submenu-img]() Dibakar Banerjee says people didn’t care when Sushant Singh Rajput died, only wanted ‘spicy gossip’: ‘Everyone was…'

Dibakar Banerjee says people didn’t care when Sushant Singh Rajput died, only wanted ‘spicy gossip’: ‘Everyone was…'![submenu-img]() Most watched Indian film sold 25 crore tickets, was still called flop; not Baahubali, Mughal-e-Azam, Dangal, Jawan, RRR

Most watched Indian film sold 25 crore tickets, was still called flop; not Baahubali, Mughal-e-Azam, Dangal, Jawan, RRR![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: DC thrash GT by 6 wickets as bowlers dominate in Ahmedabad

IPL 2024: DC thrash GT by 6 wickets as bowlers dominate in Ahmedabad![submenu-img]() MI vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

MI vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() MI vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Punjab Kings

MI vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Punjab Kings ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Big boost for LSG as star pacer rejoins team, check details

IPL 2024: Big boost for LSG as star pacer rejoins team, check details![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR

IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Deserts around Saudi Arabia's Mecca and Medina are turning green due to…

Watch viral video: Deserts around Saudi Arabia's Mecca and Medina are turning green due to…![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

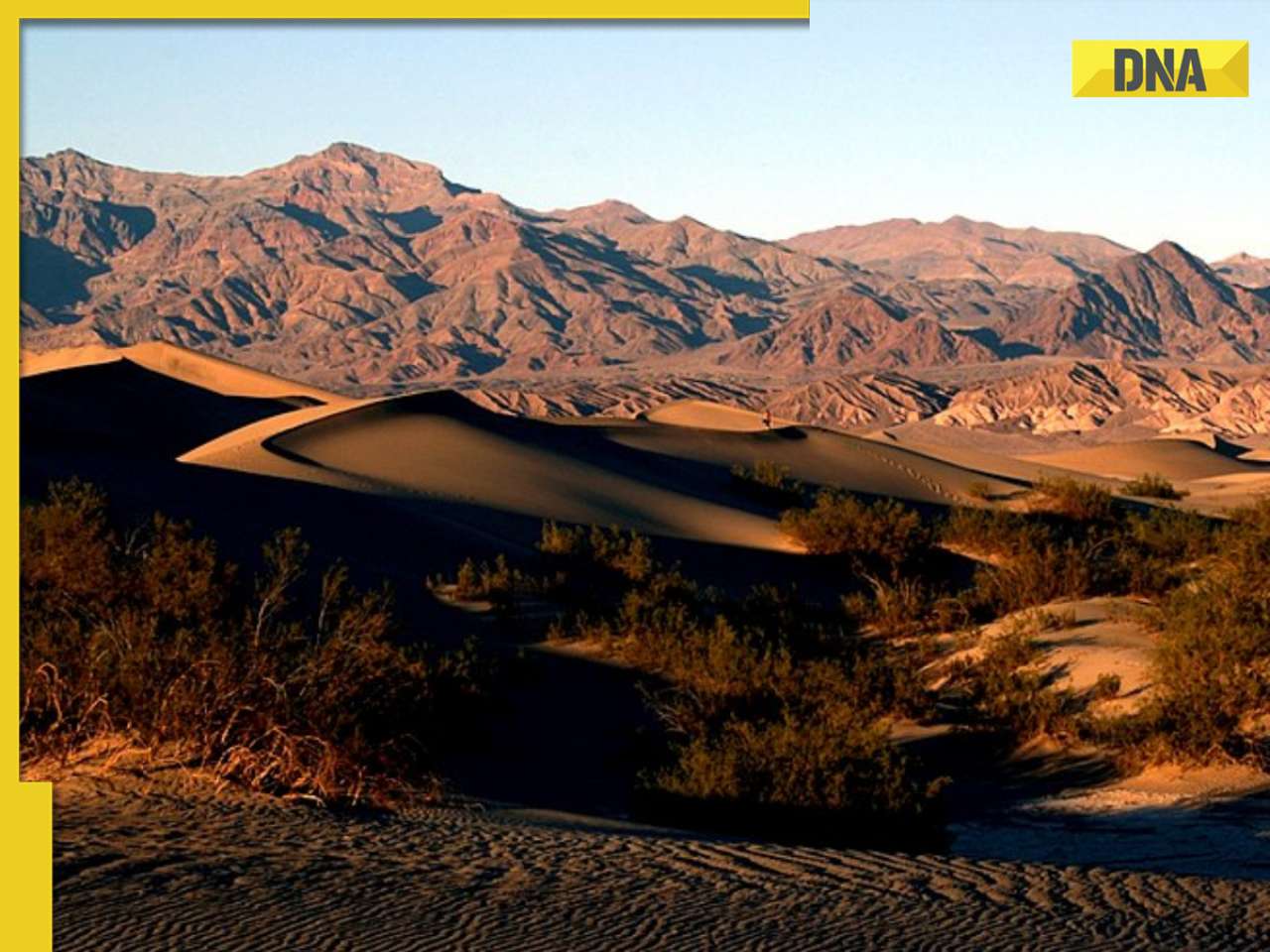

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here

Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

)

)

)

)

)

)

)