Page by page, sheaf by sheaf, file after file and book after book, the Maharashtra State Archives has been extending the life of its 14 crore records. Dating back to the 16th century, the documents are a treasure trove of a bygone era, points out Marisha Karwa.

Letters by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, notes from his son Sambhaji, hand impression and seals of a possible Mughal dynast, journals with entries by the Britishers for the East India Company and compilations of vernacular and English newspapers that have for long been out of print… These are but a few historical gems hiding in plain sight at the Maharashtra State Archives, or the State Record Office as it was known when it was set up in the British era.

Wrapped in Gothic architecture, the building, which also houses Elphinstone College, is a befitting residence to its vast collection of documents, journals, books and periodicals starting from the time of the Maratha empire, through the period of British East India Company's colonisation of India and the independence movement to the years since 1947.

“The department traces its history to 1821 when it was founded as the State Record Office by the Britishers. They were scrupulous at maintaining records,” points out Dr. Dilip Balsekar, the multifaceted director of the Maharashtra State Archives. It was post independence that the custody of the records — carefully indexed, catalogued and stacked on floor-to-ceiling shelves by successive administrators — fell into Indian hands.

Maharashtra State Archives director Dilip Balsekar

The Maharashtra State Archives now has more than 14 crore documents across its offices in Mumbai, Pune, Kolhapur, Aurangabad and Nagpur. A majority of these, about 11 crore, are in Mumbai. “The documents here are from the Modern period, mostly related to the East India Company. The documents in Pune, which was the seat of the Peshwas, are from their time. Likewise, Aurangabad, which fell under the Nizam of Hyderabad, has Persian and other documents related to the Nizam's rule,” says Balsekar, who studied history at Pune University.

The Maharashtra State Archives holds a vast collection of about 14crore records at its offices in Mumbai, Pune, Kolhapur, Nagpur and Aurangabad. Researcher Anil Rao (in pic) looks up the history of annual exhibitions of the Bombay Art Society at the Mumbai branch at the Elphinstone College building.

“The oldest documents are from the year 1590, and quite a few are in the Modhi script, which transformed sometime in the early 19th century into what we now recognise as Marathi,” adds Balsekar, a polyglot who comprehends not only Modhi, but also the value that these documents hold for research scholars, academicians, students and history lovers. “As a custodian, it is my duty to preserve these documents so researchers can benefit from the information they contain.”

One such researcher, Dinyar Patel, who last visited the Maharashtra archive in Mumbai in 2012, found a treasure trove of information not just limited to contemporary Maharashtra but also including Gujarat, Sindh, parts of Karnataka, the Middle East, and parts of East Africa at the Mumbai branch of the archive. “I've come across some spectacular material, such as the papers for processing the warrant for Gandhi's first arrest in India in 1922, communication from the Baroda darbar in the 1870s written on gold-embossed paper, and a number of rare maps of Bombay city and the Gujarati coast,” writes Patel in an email from Boston where he is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History in Harvard University.

A worker inspects a microfilm at the Mumbai office of Maharashtra State Archives. Director Dilip Balsekar estimates that it will take another 10 years for all records to be put on microfilm.

Restoring history

Dealing with history though requires care, and handling paper that is 200-300 years old calls for an altogether different level of caution. Fraying sheets, paper brittle to the touch and book binding tethered to the last thread are commonplace on the formidable stacks of the Mumbai archives. “A lot of the archival material is very brittle and has suffered from weather damage, and this damage is accentuated every time it is consulted by a researcher,” notes Patel, pointing out that the Mumbai building is open to the elements and not properly temperature controlled. “It appears that most material has not been de-acidified, which means that it can turn brittle and fall apart. Some material is so fragile that it breaks apart at the slightest touch, and gets scattered by the fans whirring overhead in the reading room. A lot of old, rare newspapers are no longer accessible because they are too brittle.”

A letter by Chhatrapati Shivaji written in the Modhi script, c. 17th century.

Archive officials and workers tackle this the best way they can. A retinue of four to five 'record lifters' take position at various levels on the stacks to retrieve documents from the higher shelves to avoid damage during handling. Books, diaries and journals are periodically fumigated and delicate sheets and papers are placed between tissue and chiffon (a sort of a conservation lamination). But what may well turn out to have the most impact on conservation is the archives' digitising and microfilming initiative (reproducing a document on film) of all its records at state archives offices in Mumbai, Pune, Kolhapur, Aurangabad and Nagpur. While the microfilming work has been going in for more than two decades now, Balsekar says that scanning and digitisation of records started in earnest in May 2002.

A letter with a seal and handprint, possibly written by a descendant of the Mughal dynasty.

Nine German make scanners and 14 microfilming machines from Japan attached to respective desktop computers occupy the archives' corridor space. Working mechanically, the scanning operators place two sheets at a time from dusty old files or journals on the scanner, press a button till the scan shows up on the computer screen, flip over the sheets, press the button again to scan before moving on to the next pair of pages. Standing on their feet for a better part of their work day, each operator scans about 800 pages per day. It is mundane and monotonous work, and yet they have to maintain utmost care while delicately handling each ageing sheet, file, book and journal so as not to deteriorate its condition further. Given the seemingly infinite number of pages pending scanning, it is apparent why these men and women are oblivious to the papers they touch. “These are historical documents, and we cannot be in a haste to complete the digitising and microfilming. It has to be done carefully,” says Balsekar of the ongoing effort.

The oldest record at the archives in Mumbai is this Surat Factory Diary from the year 1660.

The state government allocates the department a budget of about Rs.5-6crore every year, says Balsekar, but the manpower required for is inadequate. He anticipates that it will take another five years for all the records to be digitised, and perhaps another decade for the microfilming to be complete at all the offices. The plan is to eventually build a website with a detailed index, listing the 14 crore records the state archives holds, what the record is (letter, file document, diary, journal, newspaper, etc), which city it is located in and whether it can be accessed online. “I'm keen to have researchers, whether they are based in India or abroad, to be able to access the documents in our archives,” says Balsekar.

Collections abound of old and now out-of-print newspapers, such as [l-r] The Bombay Chronicle, Darpan and Bombay Courier.

Patel says that while digitisation is a welcome move and will help limit damage to the records, it also needs to be complemented by better preservation practices and a better physical environment. “Even if a document is digitised, we still need to make sure that it is properly preserved and housed. We do not know about the longevity of digitised material, and inevitably there is still much material that requires consultation in person.”

A retinue of ‘record lifters’ take position at various levels on the stacks to retrieve documents from the higher shelves to avoid damage during handling.

Maharashtra State Archives branches

1) Mumbai: ~11 crore documentsMumbai: ~11 crore documents

2) Pune: ~4 crore documentsPune: ~4 crore documents

3) Kolhapur: ~1.25 crore documentsKolhapur: ~1.25 crore documents

4) Nagpur: ~50 lakh documentsNagpur: ~50 lakh documents

5) Aurangabad: ~40 lakh documents

Each scanning machine operator scans an average of 800 documents per day. The Mumbai office has nine German-make scanners.

Upkeep of documents at archive

While many academics and researchers rue the state of archives in India, and the poor upkeep of written heritage, there are some measures that the Maharashtra State Archives takes to preserve the documents it holds.

- Old books and journals are prone to damage by termites. To prevent this, workers periodically fumigate the collection in fumigation cabinets. Books are placed in the cabinet in which paradichlorobenzene is released for up to 10 days, says Santosh Dhanawade of the State Archives.

- Dusty sheets and pages are immersed in a solution of water to which calcium carbonate (CaCo3) is added and then dried.

- Extremely delicate or brittle pages which are prone to tearing are layered between tissue and chiffon using carboxy methyli cellulose (CMC) paste, says Dhanawade.

All images by Hemant Padalkar/dna.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

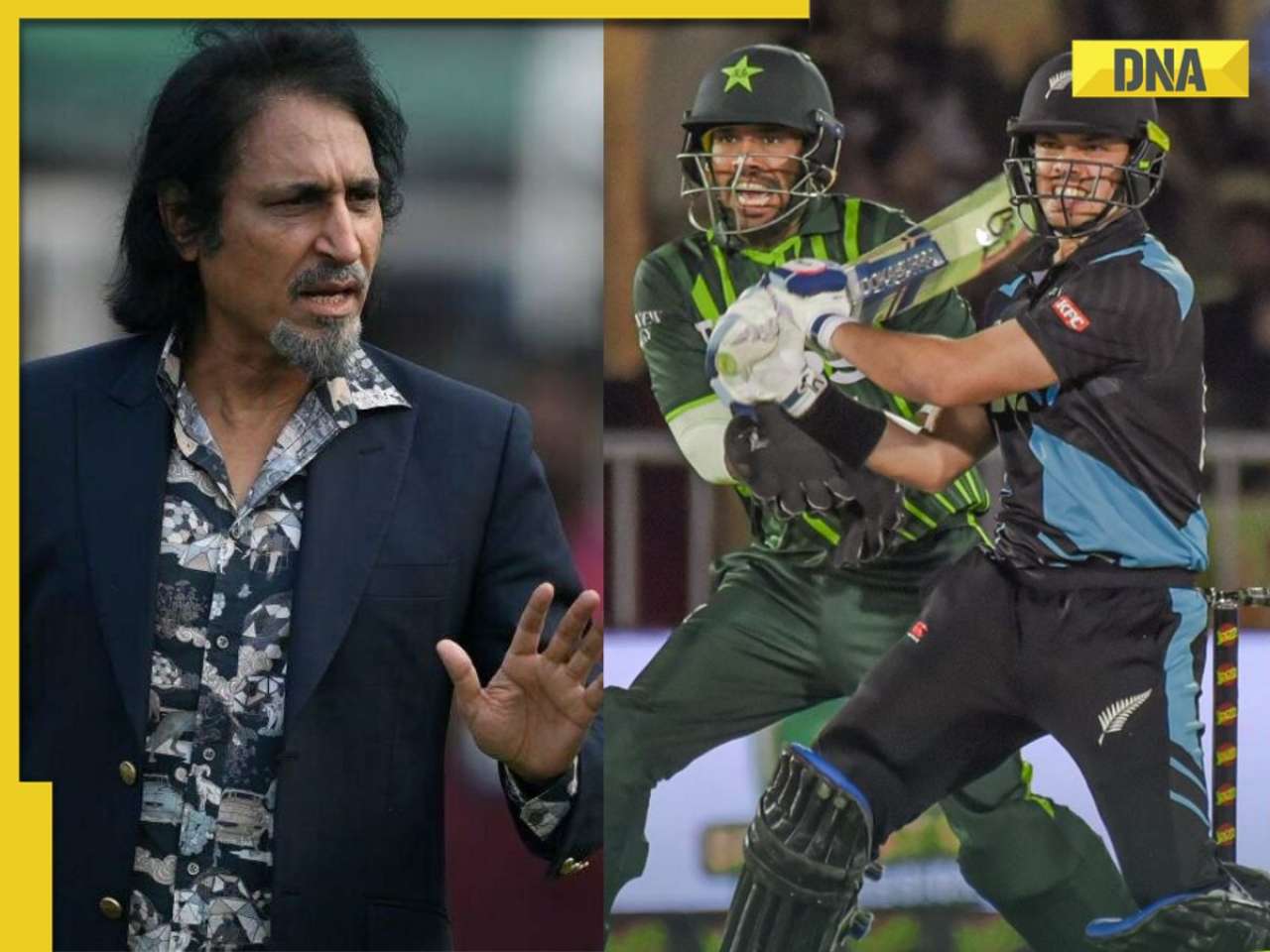

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

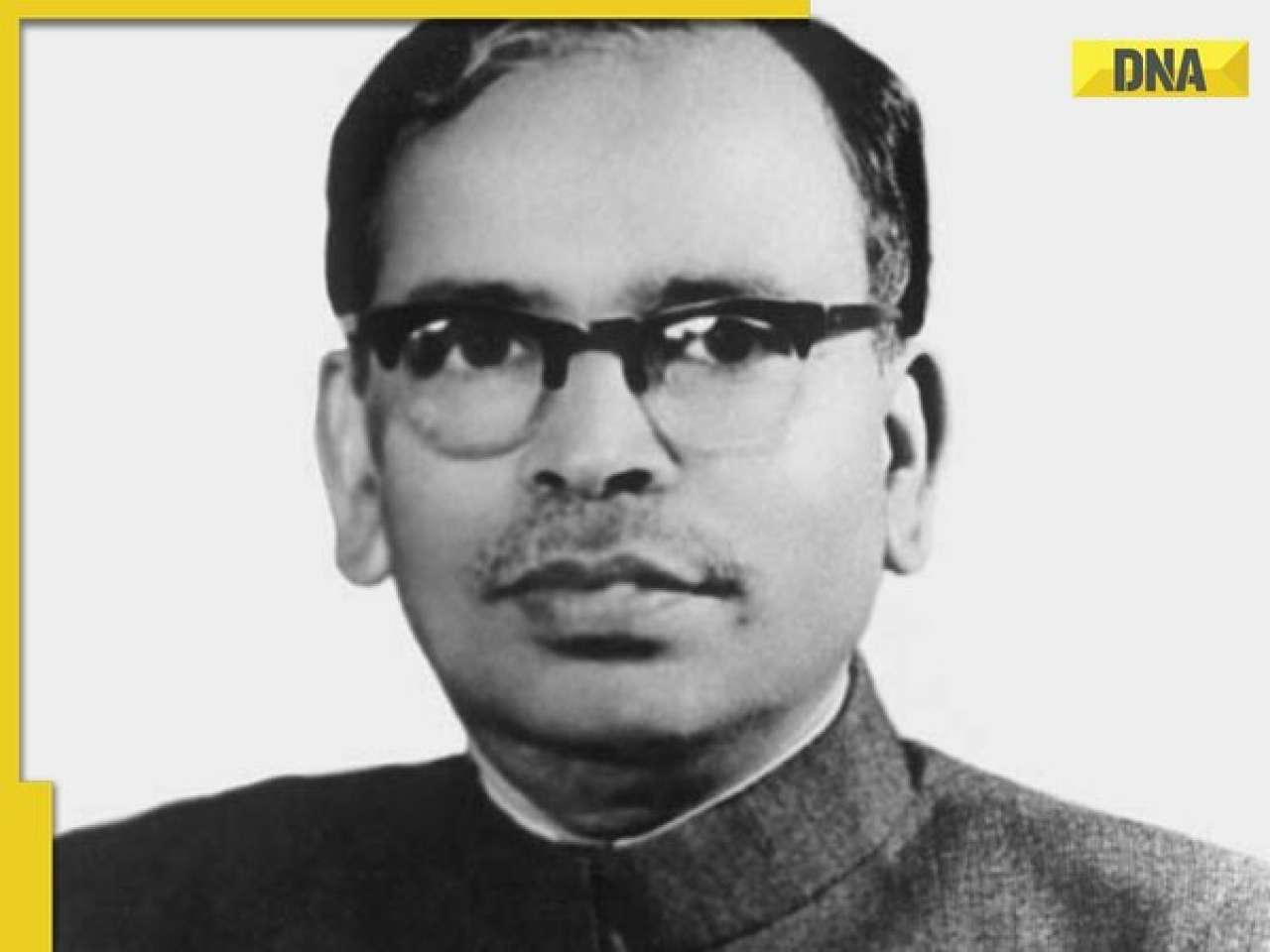

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

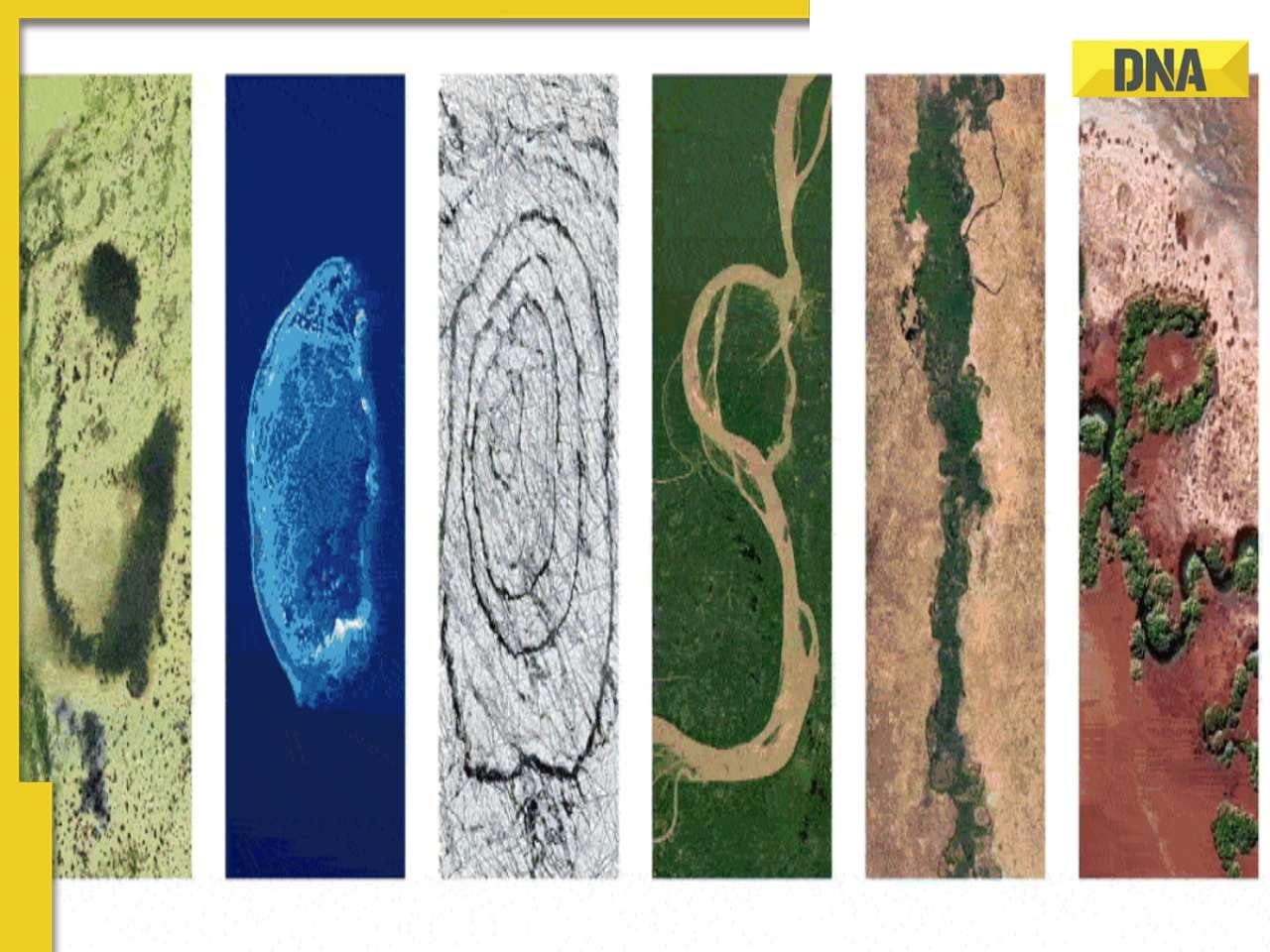

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)