Childhood friends Mary Kom and L Sarita Devi are the iron ladies of Indian boxing. Both have done the country proud at the Asian Games in Incheon. Chander Shekhar Luthra traces the arduous paths of the bravehearts from Manipur

If not for the 'ray of hope' called boxing, MC Mary Kom and L Sarita Devi would have lived in darkness — quite literally. Hailing from the insurgency-hit state of Manipur, where the spectre of death, fear and uncertainty looms large over commoners, these brave women of Indian sport have infused a new energy and given the youth the power to dream.

Now a mother of three, Mary grew up in a village called Kangathei, located 20km from Imphal, the state's capital. Born to jhum (slash and burn agriculture popular in the Northeast) cultivators Tonpa and Akham Kom, Mary helped her parents by caring for her younger siblings (two sisters and a brother). Electricity was unheard of in the region. The fight for survival was as hard for the Koms as it was for the millions in the Northeast. Lack of basic facilities, the menace of drug addiction among the youth and the growing insurgency in the region were a stark reality the Koms had to contend with.

Mary's neighbours were Sarita and Dingko Singh. It was Dingko who gave hundreds of underprivileged children in the region hope by winning a gold medal at the 1998 Asian Games in Bangkok. As a young girl, Mary was one of them. And even after all these years, she has not forgotten the pain and hunger of those days.

The tattoo of a boxing glove on her left shoulder narrates the story of Sarita's life, and her dedication to the sport. Sarita and her six siblings had to drop out from school for want of money. It was only after she got a job that things started moving in the right direction.

Pain inside the ring

Ironically, the man who has coached both the leading ladies of Indian boxing was initially sceptical of coaching Mary and Sarita because of their frail bodies. But the determination and grit shown by the girls floored him and he took them under his wings. "They came with a dream. Not of becoming world champions, but of helping themselves and their families overcome poverty," recalls L Ibomcha Singh, talking about how his wards embraced the sport.

After the struggles of their early lives, Mary and Sarita endured pain in the boxing ring; the girls trained at the same centre where Dingko had trained for his Asiad gold medal. But the physical pain didn't bother them.

Knowing too well that only a medal-winning performance would fetch them a good and permanent job in their home state, they kept fighting without caring about those innumerable punches they had to take during camps and competitions.

"You can never imagine the pain of going to sleep hungry," Mary had told this reporter. "If you don't have a livelihood, you will struggle all your life. And getting a government job is probably the most difficult thing in life."

Fighting for glory

Mary is 32. And today, she trains harder than ever before. Ever since women's boxing became an Olympic event in 2012, the rules of the games changed. During Mary's heyday, there were just five or six quality boxers in the world. But the Olympic bout in London, where Britain's Nicola Adams gave her the hammering of her life in the semifinal, made Mary realise that time was running out. Even before the Asian Games began, Mary knew this was her last chance to win a medal at the continental games. She was aware that beating Pinky Jhangra, her younger rival, at the trials would be as tough as winning a Games medal. Jhangra had beaten Mary at the trials held prior to the Commonwealth Games.

Ditto with Sarita. It was only earlier this year that Sarita, like Mary, resumed her boxing career after becoming a mother. It's tough to resume training when you know that your baby needs you more than anything else. But that's when her, who despite her failing health, accompanied Sarita to Delhi for camps to help out with the baby.

Sarita wanted to make a point this time around. "I want to give him gold," she had told dna after a gruelling practice session. "I want to set an example that I can be a good boxer and a good mother too. I'm not neglecting him and spending most of my free time playing with him," she added.

Besides, a gold medal in Incheon could well have compensated for all those moments of unhappiness when she was being treated unfairly by the Indian Boxing Federation (the body that regulated the sport before the newly-formed, Boxing India). Time and again, she was forced to move up to a higher weight category in order to accommodate her more celebrated friend, Mary.

But while Mary rose to glory, Sarita's dream was shattered. The 29-year-old left the Incheon Games Village in tears, distraught over the judges' decision to declare Korean Park Li-Na a better pugilist in the ring that day. But the gutsy girl refused to accept the bronze medal, saying "she deserved either silver or gold".

Official indifference

Even as her husband went around borrowing money to pay the required $500 to lodge a protest against the judges' decision, India's Deputy Chief De Mission Kuldeep Vats chose to stay away. Soon after, International Boxing Association (AIBA) officials soon ganged up against Sarita. The Indian Olympic Association (IOA) officials then pressured Sarita into tendering an apology. "If not, you will be banned for life," they threatened her. Left with no choice, Sarita said sorry.

Back home, a death-like silence prevailed after Sarita was denied her biggest-ever medal. Her younger brother, Rakesh Laishram, summed it up: "After going through such struggles in life, it made all of us so sad to watch Sarita cry on TV after that bout. The last time I felt so sad was when my brother died. She deserved to win that particular bout but they (AIBA) stole her chance of entering the final."

So why did IOA and Boxing India (BI) fail Sarita during her most difficult time. It's common knowledge in sport circles that BI officials are trying to save their skin. After all, the body has only got temporary recognition from AIBA. "Indian sport is never about sportsmen. It is about the officials, who run the various federations like their fiefdoms. When was the last time an official sacrificed his seat to save a sportsperson?" said a boxer, requesting anonymity.

Role models for millions

By winning a gold and reluctantly settling for a bronze, these Manipur pugilists have given an impetus to the contact sport not only in India but across the region. Quick to read the signs, AIBA is hoping to cash in on Mary's popularity by launching the World Series Boxing league for women in the immediate future.

Now, 17 years after she first entered the sport, Mary boasts a trophy cabinet like no other. An Olympic bronze, an Asian Games gold and five World Championships later, she's a different person from the one who obstinately rejected the post of a sub-inspector in Manipur Police because she believed a world champion deserved better.

If Kom is now a Superintendent of Police, then a promotion for Sarita, now a deputy SP, could well be in the offing. But it remains to be seen if Sarita escapes a ban. Whatever the future has in store for these two iron ladies, millions in India look up to them.

![submenu-img]() First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..

First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..![submenu-img]() Apple iPhone camera module may now be assembled in India, plans to cut…

Apple iPhone camera module may now be assembled in India, plans to cut…![submenu-img]() HOYA Vision Care launches new hi-vision Meiryo coating

HOYA Vision Care launches new hi-vision Meiryo coating![submenu-img]() This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...

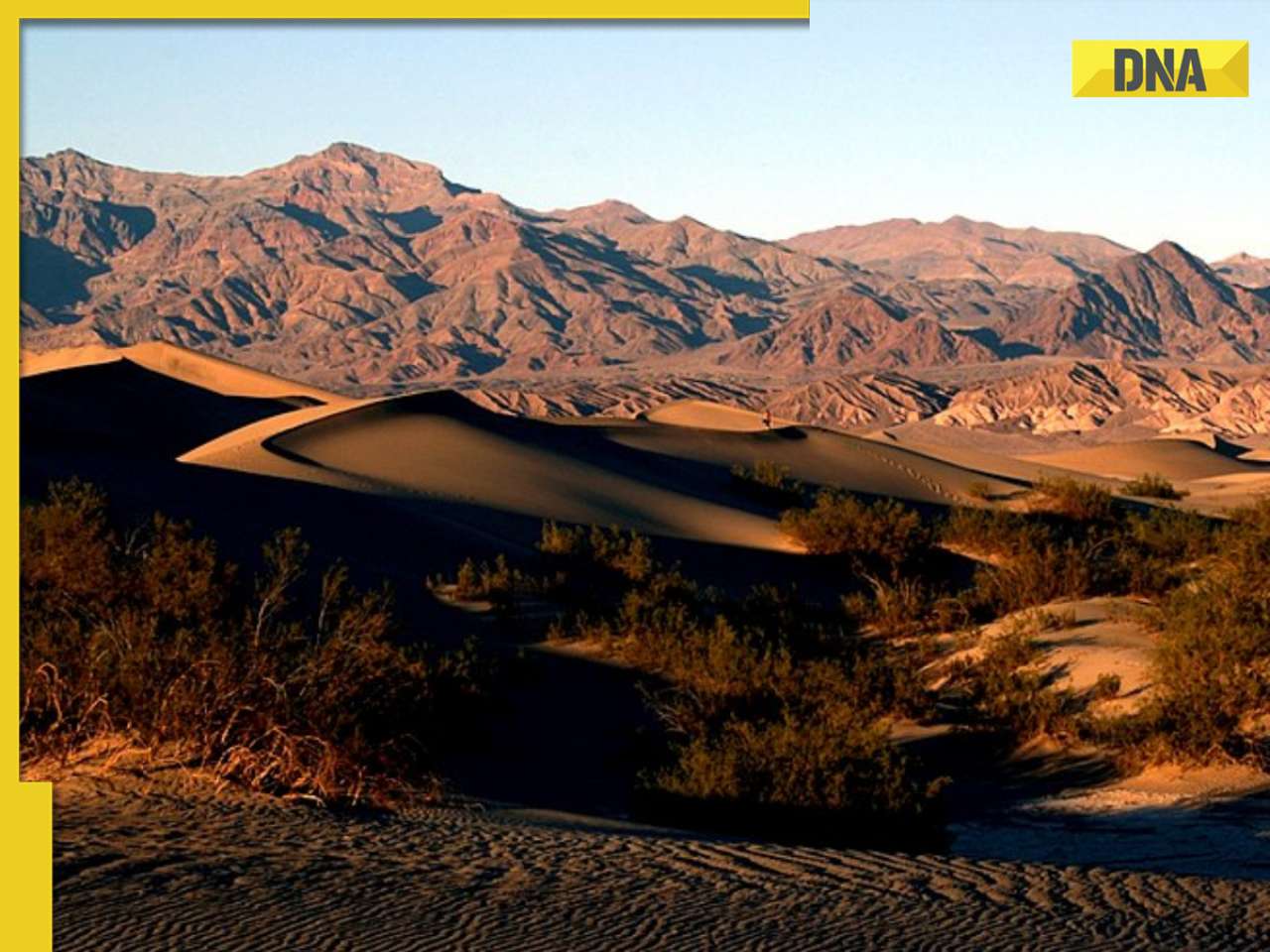

This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

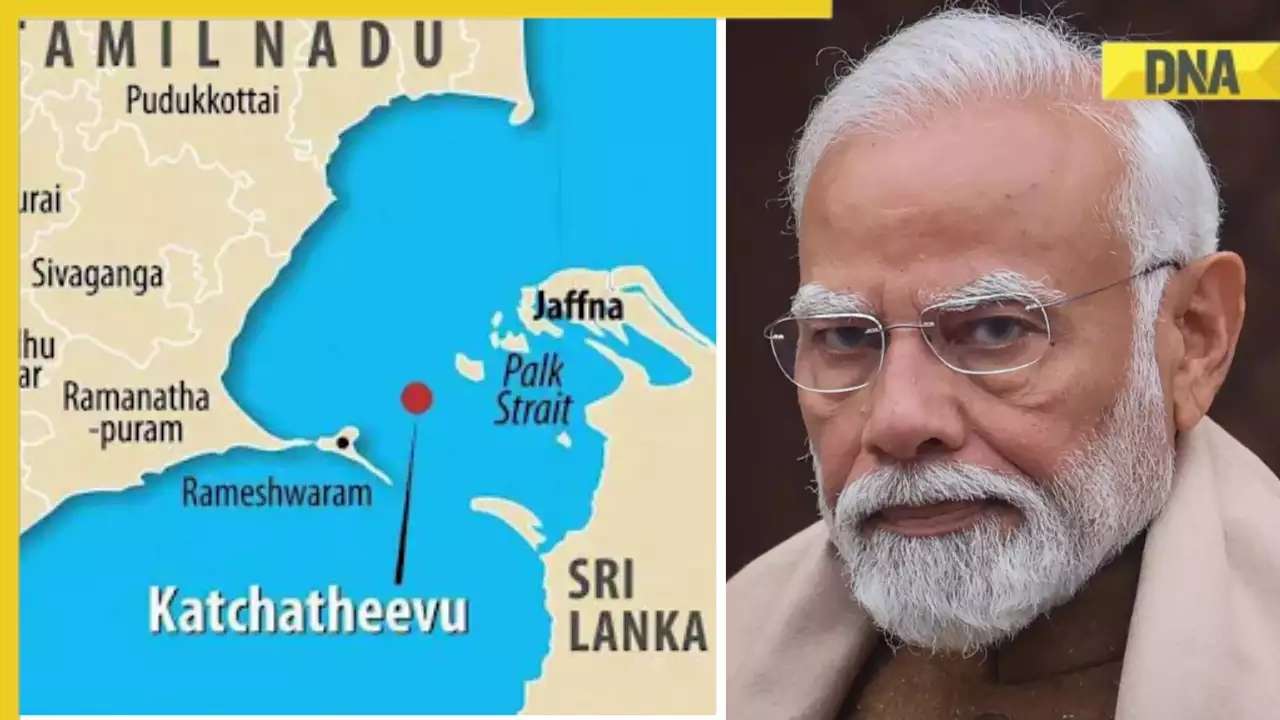

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..

First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..![submenu-img]() This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...

This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...![submenu-img]() Salman Khan to return as host of Bigg Boss OTT 3? Deleted post from production house confuses fans

Salman Khan to return as host of Bigg Boss OTT 3? Deleted post from production house confuses fans![submenu-img]() Manoj Bajpayee talks Silence 2, decodes what makes a character iconic: 'It should be something that...' | Exclusive

Manoj Bajpayee talks Silence 2, decodes what makes a character iconic: 'It should be something that...' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Meet star, once TV's highest-paid actress, who debuted with Aishwarya Rai, fought depression after flops; is now...

Meet star, once TV's highest-paid actress, who debuted with Aishwarya Rai, fought depression after flops; is now... ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR

IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR![submenu-img]() GT vs DC, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs DC, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Delhi Capitals

GT vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'I went to...': Glenn Maxwell reveals why he was left out of RCB vs SRH clash

'I went to...': Glenn Maxwell reveals why he was left out of RCB vs SRH clash![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here

Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

)

)

)

)

)

)

)