The story of 'Mountain Man' Dashrath Manjhi moved a nation to tears, but Yogesh Pawar delves deep to find that millions in rural India still grapple with lack of grassroots health infrastructure, basic amenities, and most of all – malnutrition

Barely a month to the release of Ketan Mehta's Manjhi – The Mountain Man, based on the real life story of a poor contemporary Shah Jahan, Dashrath Manjhi, who toiled for 22 years to break a mountain for love, the trailer has garnered nearly four lakh hits in less than a fortnight. But the buzz about how the film could work with both classes and masses, is generating little excitement in the Dalit tola off Gahlaur village in Bihar's Gaya district where Manjhi's family lives. "My father toiled to break down a mountain for 22 long years with a only chisel and hammer breaking down a 25 foot tall and 30 foot wide mountain reducing the distance from Atri to Wazirganj block in our district to barely one km from 75. While others are benefiting from his work with movies and tv shows even now, we're worried about where the next meal will come from," complained Bhagirath Manjhi. "Aamir Khan promised to help us in March 2014 when recording his show but no real help came."

In a cruel twist of fate, though his father broke down a mountain which came between his mother Falguni Devi's access to healthcare leading to her death in early 1959, 56 years later this has done little to improve access to health care for the village. Last year his wife Basanti Devi who had developed gynaecological problems died on April 1st barely a month after the family had recorded a Satyamev Jayate episode. His 19-year-old school drop-out daughter Lakshmi who is herself struggling with a rasping cough, angrily remembers her mother. "We tried to reach Aamir Khan's office but there was no response. His staff kept saying they'd get back even when I pleaded that I don't have money for the shraadh ceremony."

While repeated attempts at reaching Aamir Khan Productions for reaction drew a blank, Bhagirath asks, "How will just having a path through the mountain help? We couldn't afford medicines and the doctor's fees." Both Bhagirath Manjhi and his wife Basant Devi made Rs 1,000 a month for cooking the midday meal at the local primary school. Since her health began failing in 2013 she couldn't even move out of their hut. The family had to then make-do with only half its income. His daughter in law Lakshmi recounted borrowing money from neighbours to take make three trips to the nearest government hospital in Gaya. "But they would either not have working equipment and medicines or doctors. Just going back and forth left us with a debt we're still repaying. All we could do was use home-remedies every time she complained of discomfort or pain and await her death."

Ketan Mehta hopes his film will help highlight the plight of the region he calls "one of the most backward and poor" in the country. "After over six decades of Independence, it's shocking to see people there still living like they would a 100 years ago. There's no electricity. When we used to climb the mountain for our shoot, the moment the sun went down, the region would be enveloped in pitch darkness for as far as we could see. Not just Manjhi's village, but several others nearby are abject poor. You can't find any grown-ups because they've all left in search of work, only old men and women and young children remain. Unsurprisingly, its a landscape which has a strong presence of Naxals."

Mehta too questions why development has merely come to mean multi-lane highways, big dams, malls and multiplexes and laments how little has changed for the poor, from Jeevo in his debut Bhavni Bhavai in 1980 to his biopic on Dashrath Manjhi. "Growth has come to mean a greater concentration of wealth in the hands of the fewest of the few. The skewed nature of our development model has to change if this country has to move to holistic development and growth."

Bhagirath's comment nails it. "Poor like us may break one or two visible mountains but what does one do about the invisible ones?"

Nearly 1,800 km away in Madhaliwadi village of Shahapur tehsil barely a two-hour drive from the country's financial capital, in Thane district, Dilip Laxman Mundola and his wife Mukta should know a thing or two about the 'invisible mountains.' Last monsoon, their daughter Swati (who would have been five now) starved to death. This year, already, their son, Kailash, 4, and 6-month-old daughter Sarika have been diagnosed with severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Their condition, so serious that they they had to be taken to the local primary healthcare centre (PHC). "Kailash can't even walk and has to be carried," says Mundola of his emasciated son who is barely 6 kg.

But Kailash and the Sarika aren't the only ones starving in this Thakar adivasi village. The anganwadi (government-run mother and child care centre) register of the village (which has a population of 300) shows that 27 children in the 0-6 age group are critically malnourished!

Its a story that repeats itself not only in the remote interior Korku villages of Melghat in Amravati district but in the Palghar, Thane and Raigad districts of Maharashtra - where 45,000 children in the 0-6 age group die of malnutrition every year - all of which are well connected with the bustling cities of Mumbai and Pune thanks to multi-lane highways and railway lines which run through them. "Apart from the ease of getting around this has not translated into any real change for the way the adivasis in these areas live. The roads and railway lines only serving as a cruel reminder of how development zips past without being bothered about them," laments activist Shiraz Balsara of the adivasi advocacy group Kashtakari Sanghatna, who has been working with the tribals in Jawhar, Mokhada and Dahanu for over three decades.

"Not that rural hospitals and primary health care centres are any shining examples of great facilities, but health is not only about institutionalised healthcare. The conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems like the economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies and political systems shaping the conditions of daily life are equally important. For as long as these root causes aren't addressed, intervention amounts to knee-jerk reaction. That's exactly where most government welfare schemes and their implementation falls and fails."

In a bid "to curb malnutrition which sets the stage for debilitating health lifelong," the Maharashtra government spends Rs. 300 crore yearly to provide kids with "micronutrient-fortified, energy-dense" food (like chikkis, which have come under the scanner following the recent scam) under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). Ironically a study by Support for Advocacy and Training to Health Initiatives (SATHI) last May found the project a waste of money and the food supplied being not up to the mark.

Apart from freshly prepared khichdi and dal given at anganwadis, the government gives upma, sheera or chikki as take home ration (THR) under ICDS. The SATHI study found that THR's use and efficacy claims were falsified. The food barely has any nutritional value. Conducted in Pune, Nandurbar, Gadchiroli and Amravati, the study found children and their parents preferred cooked food to instant upma packets that are distributed as THR. The most damning finding is that the extent of both moderate and severe malnutrition is almost double in areas where THR is given, compared to where cooked food is given to children.

Most children in the study complained that THR was inedible. Over 79% of the respondents said they feed it to animals or use it as bait for fishing. At least 11% found it so bad that they threw it away. Over 69% of the respondents said the upma tastes bitter, 22.4% said it was salty and 58% said it was stale. While a government resolution (GR) claims every 16.3g of THR should have 567cal of energy. But when mothers heated it after adding water, it was found to weigh 7.5g with 130cal of energy. The study, which monitored 2,110 children in 15 villages, also found that the supply of THR was both irregular (once/twice a month) and inadequate (less than 60% were getting it at all).

Dr Arun Gadre of SATHI underlines, "Ideally, children should get freshly cooked nutritious food... Despite being one of the wealthiest states in the country, almost half of Maharashtra's children are undernourished, according to the government's own statistics." Pointing out how more children die of mild or moderate malnutrition (33,000) than of severe malnutrition (12,000), he said, "This makes monitoring anganwadis much more important. The international trend is for every 3-4% increase in per capita income, the underweight rate should decline by 1%. But that is not happening in India."

Echoing him is doctor and health activist Dr Ravindra Kolhe, who has worked with adivasis for nearly 30 years. "In 2006, the state's Infant Mortality Rate (IMR), which used to be 200 per 1000 children, came down to 40 per 1000 children. But instead of reducing further, it has now gone up to 66 and is climbing." According to him, this is a direct outcome of the pathetic state of service delivery systems. "Instead of strengthening grassroots health infrastructure, like PHCs and rural hospitals, the government spends more on specialised high-cost healthcare. This kind of abdication of social responsibility of the state where TB, safe delivery and malnutrition go unaddressed is why we are in such a mess."

Seems like a tall order? Surely not tougher than the mountain Dashrath Manjhi broke...

Pre-pregnancy deficits in Indian women more common than in women hailing from African countries: Study

42.2% of pre-pregnant women in India are underweight compared to 16.5% of pre-pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa. In both regions, women gain little weight during pregnancy, but because of pre-pregnancy deficits, Indian women end pregnancy weighing less than African women do. Despite being from relatively wealthier families, Indian children are significantly shorter and smaller than African children. These differences begin very early in life, suggesting that they may, in part, reflect differences in maternal health.

Source: Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, February 2015

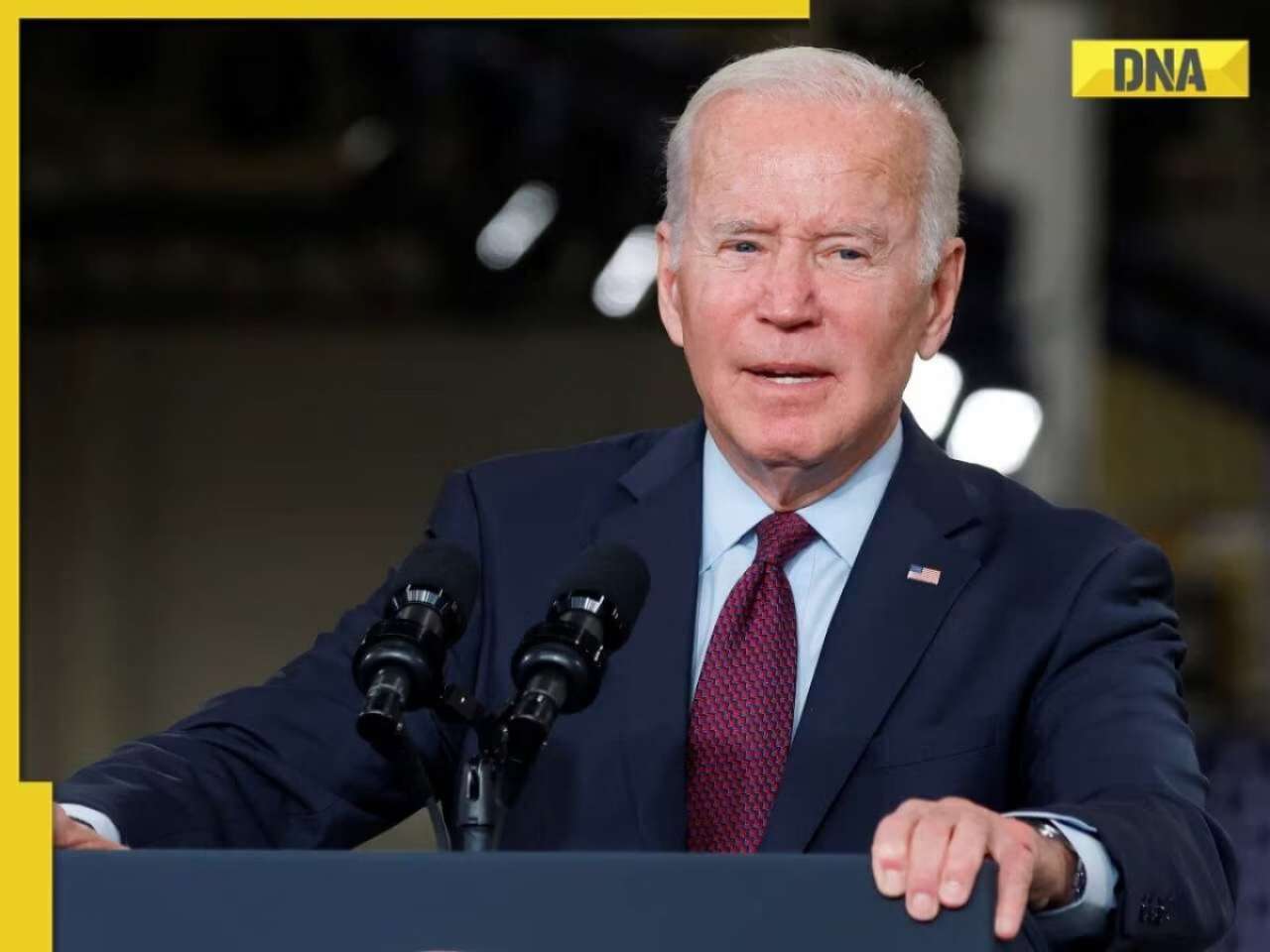

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)