Does the decline in the worship of Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, over Laxmi, the Goddess of wealth, reflect a materialistic society’s quest for money and power? In the build-up to the soon-to-begin Navratri festival celebrating Devi, Yogesh Pawar ponders questions of transfer projections and patriarchal constructs as he speaks to believers and analysts.

Does the decline in the worship of Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, over Laxmi, the Goddess of wealth, reflect a materialistic society’s quest for money and power? In the build-up to the soon-to-begin Navratri festival celebrating Devi, Yogesh Pawar ponders questions of transfer projections and patriarchal constructs as he speaks to believers and analysts.

Ya kundendu tushara haara dhawala, Ya shubhra vastravarta

Ya veena varadanda mandita karaa, Ya shweta padmasana |

Ya Brahma Achyuta Shankara – prabhrutibhir devaha sada poojita

Saa maam paatu Saraswati Bhagavati nihshessa jaddya apaha ||

(The one who is pure white like the Jasmine, has the coolness of the moon, the brightness of snow and shines like a garland of pearls, the one covered in pure white raiments/ Whose hands are adorned with the veena (a stringed musical instrument) and the boon-giving staff, as she sits astride a pure white lotus/ Always adored by Gods like Brahma, Achyuta (Vishnu), Shankar and many others / O Goddess Saraswati, protect, awaken and deliver me from my ignorance)

The rising sun’s rays cloak the room in a lovely red hue. Incense sticks work their magic as ankle-bells keep time even as the tanpura notes fill the air. Leading Kathak exponent and guru Acharya Ganesh Hiralal Hasal of the Jaipur gharana joins his students in Mumbai’s Kandivali in a prayer to the Goddess of learning, an uncommon choice of composition (by one of the holiest saptarishis, the sage Agastya) for a dance class.

“The Goddess of learning - Saraswati is one of the most ancient in the Hindu pantheon, yet in today's times when it comes to worship, apart from the obligatory puja every year she's largely forgotten. That is why when we do the Mangalacharan invocation in the beginning I deliberately choose this prayer,” he remarks, on the sidelines, later.

Why do most works invoke Lakshmi and not Saraswati? He laughs. “Its not like that. But in an era when everybody is in a mad rush chasing money, many feel the blessings of the Goddess of Wealth are all that matters,” and continues with a tinge of sadness, “People perhaps its felt that once you have money, all else will follow, a mark of the Kaliyuga we live in.”

He points out how there are many beautiful compositions in the scriptures in praise of Saraswati. “But if not as the wealth-showering Devi even audiences want to see Her as a slayer of demons armed to the teeth, like Amba, Durga, Chandi or Kali.” According to the septuagenarian dance guru, this is merely a transfer-projection of the way society sees women.

“If she brings dowry or other material gifts, she gets respect. But if she wants her due otherwise, she has to fight for space. Look around you. A subdued, mellow woman is often seen as little more than a push-over and disregarded by everyone around. Perhaps why, a contemplative Saraswati in her white raiments, lost in the music of her veena doesn’t have the same resonance as other fiery Goddesses, the Mother Manifest, strong, powerful, at once, fierce and fearsome.”

He admits though, that dance too, shows this preference for the fiery, in choice of themes. “When you are on stage, powerful demon-slaying can be more appealing than tranquility and peace. The former can be interpreted through more dynamic mudras, abhinaya and pure dance and lends itself to more dramatic presentations. Unfortunately this hunger for the loud and the desire of artistes to feed that hunger have become a vicious cycle of sorts.”

***

Across the city, traffic is picking up at its busiest node, the Haji Ali dargah circle. A few metres away, the Mahalakshmi temple is already crowded. “Namastestu Mahaamaye Shripeetha Surapoojite/ Shankha Chakra gadaahaste Sri Mahalakshmi Namostute. (I bow down at Thy Lotus Feet/ Thou art the destroyer of delusion and the source of all prosperity/ who is worshipped by all the Gods/ who holds in her hands the conch shell, the discus and the club/ Oh, Mahalakshmi, I bow down to Thy Lotus Feet), chants Breach Candy resident, Jatin Shah, 48 who unfailingly worships here in the morning, propitiating the Goddess with a coconut, jaggery and flowers. “I deal in stocks which in a sense is Lakshmi. If not here, where else will I go worship?” he asks offering us prasad. He talks about the strict nine-day fast and rituals he’ll observe for Navratri in honour of the Goddess.

Narayan Prabhudesai, 76 the priest who performed the puja for Shah, has been listening in to the conversation. He decides to join in. “If it weren’t for the Goddess Mahalakshmi where would the country’s financial capital be?” he asks and recounts how the then Governor of Bombay William Hornby wanted to unite, what were essentially seven islands cut off by the sea, into one. Accordingly, work on building an embankment to block the Worli creek and prevent low-lying Bombay from being flooded at high tide began in 1782. “After portions of the sea wall of the embankment collapsed twice, the chief engineer, a Pathare Prabhu, dreamt of a Godess Lakshmi statue in the sea off Worli. After a search recovered it, a temple was built in 1784 and the idol was installed.” Sure enough, the embankment has held to date. “Its all Her blessing,” grins the toothless Narayan quickly underlining that he too is from the same community as the engineer.

***

Nearly 1,500 km away in the north, Dr Radheshyam Tiwari a doctorate in Hindu mythology from Benares laments this change in the outlook of the land. “Earlier, across the subcontinent, knowledge, wisdom and scholarly pursuit were treated with utmost regard. It was not seen as a means to an end but something that people pursued with devotion... just for the love of it,” he points out. “Today we have moved so far away from Saraswati. This, when scriptures suggest, she’s Lakshmi and Durga’s elder sister. Symbolically this means both wealth and empowerment, can be yours, once you acquire knowledge. Unfortunately in a commercial world we’ve turned this whole idea upside down. Look at our billionaire thug-politicians...” he trails off in disgust.

He however wonders if the discomfort over Saraswati's story may also have something to do with why she’s almost a brush-over. “According to the Matsya Purana once Lord Brahma created Satarupa (another name of Saraswati) from his own body he became enamoured with her. To avoid his amorous gaze, she kept shifting from once place to another. Yet Brahma pursued her. He created five heads to see her all time. Finally she gave in and agreed to become his consort. The questions this will raise about incest may be a reason why Saraswati is kept on the margins.” According to him, this is typical of Indian hypocrisy on issues like incest.

Tiwari also talks about how Saraswati worship endured the rise and spread of both Buddhism and Jainism all through the third century BC. “As Buddhism moved from its earlier Theravada school to Mahayana, many elements from Hinduism were adopted and integrated. Significant among them, Gods and Goddesses in the Hindu pantheon, who had been around for millennia. In fact if you see some of the early Buddhist mandalas, along with various divinities of Mahayana Buddhism one unfailingly comes upon Goddess Saraswati in the south-west of the innermost circle, between Brahma and Vishnu,” he explains and adds, “As the Mahayana Buddhist texts went over the Himalayas to Nepal, Tibet, Java, China and eventually Japan, its amazing to see how the Goddess began finding mention in Buddhist imagery there too. For example in Tibet, she’s called Vajra-Saraswati and wields a thunderbolt (vajra) while in Japan, she becomes the Goddess Dai-Ben-Zai-Ten or The Great Divinity of Reasoning Faculty.”

***

From the banks of the Ganges, to that of the Tungabhadra in the south, this concern over decline in Saraswati worship and hence pursuit of knowledge for its sake is echoed by priests at the Sringeri matth. It is here that Adi Shankaracharya who revived Hinduism around 800 AD installed the Goddess Saraswati (or Sharada) at the first matth he established in what is now, Chikkamagalur district of Karnataka. “He was one of our most learned and in direct communion with the divine. Why do you think he installed Saraswati and not any other Goddess?” asks temple priest Ananda Swamy, who admits, people have forgotten that and only look for and follow scriptures that talk far more about other Goddesses. “By the medieval era, Saraswati stopped mattering after the first stage of life brahmacharya (as a student). Later on from grihastha (family), vanprastha (retired) and even sanyas (renunciation), all that people think of is Lakshmi,” he scoffs.

Contrasting the quiet of the temple town, with that of a Kolhapur, Maharashtra, known for its iconic Mahalakshmi temple, Swamy says. “The throng of devotees, looking to be bestowed with riches, may’ve led to Kolhapur becoming a centre of commerce and trade. But the contemplative quiet of the hills around Sringeri where one can sit in the temple courtyard and hear the gurgling of the river is beyond compare.”

***

Back in Mumbai, cultural historian Mukul Joshi points out how even Lakshmi does not escape masculinist patriarchal constructs. “It sounds very nice to hear when men talk of their wives saying, ‘Yeh toh mere ghar ki Lakshmi hai (She is the Lakshmi of my household).’ But from early Raja Ravi Verma paintings, just see how Lakshmi's feet are kept well-hidden. Even now people believe that if Her feet are free she’ll move taking all the prosperity along. In fact around Western Maharashtra when people talk of someone being filthy rich the colloquialism they resort to says, ‘tyaana kaay kami, Lakshmi pay tutun gharat padliye tyaanchya. (They scarcely have any needs, Lakshmi’s broken her leg and fallen in their house.)’ This gives you an idea of how men transfer-project their idea to control women onto the Goddess as well.”

In fact Joshi insists that the spousification of Goddesses was “a clever latter-day masculinist ploy” to link greatness of Goddesses to their spouses. “In the process many of our ancient stand-alone Goddesses of fertility and strength were pushed aside. This made way for the mainstreaming of spouses of the triumvirate of the Hindu pantheon – Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh.” He also points out, “In keeping with the matrilineal tradition which was norm of the land, many tribal and dalit still worship such Goddesses as single entities without a mandatory spouse being appended,” but quickly adds, “The twin juggernauts of Brahminisation and masculinisation however, are quickly destroying these traditions, which should in fact, be celebrated.” He admits though that practices like animal sacrifice and other occult practices associated with the worship of the some of these standalone deities has also helped push many away from them.

In parting, Hasal nails it. “Women either get treated like Goddesses and are kept on a pedestal or are seen as mere objects of lust. Till they aren’t seen as equals, our Goddesses will also not be unshackled from this masculine paradigm,” and hopes, “Perhaps it will indeed happen in the future and Saraswati will get her rightful place again.”

We can only join in that prayer.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

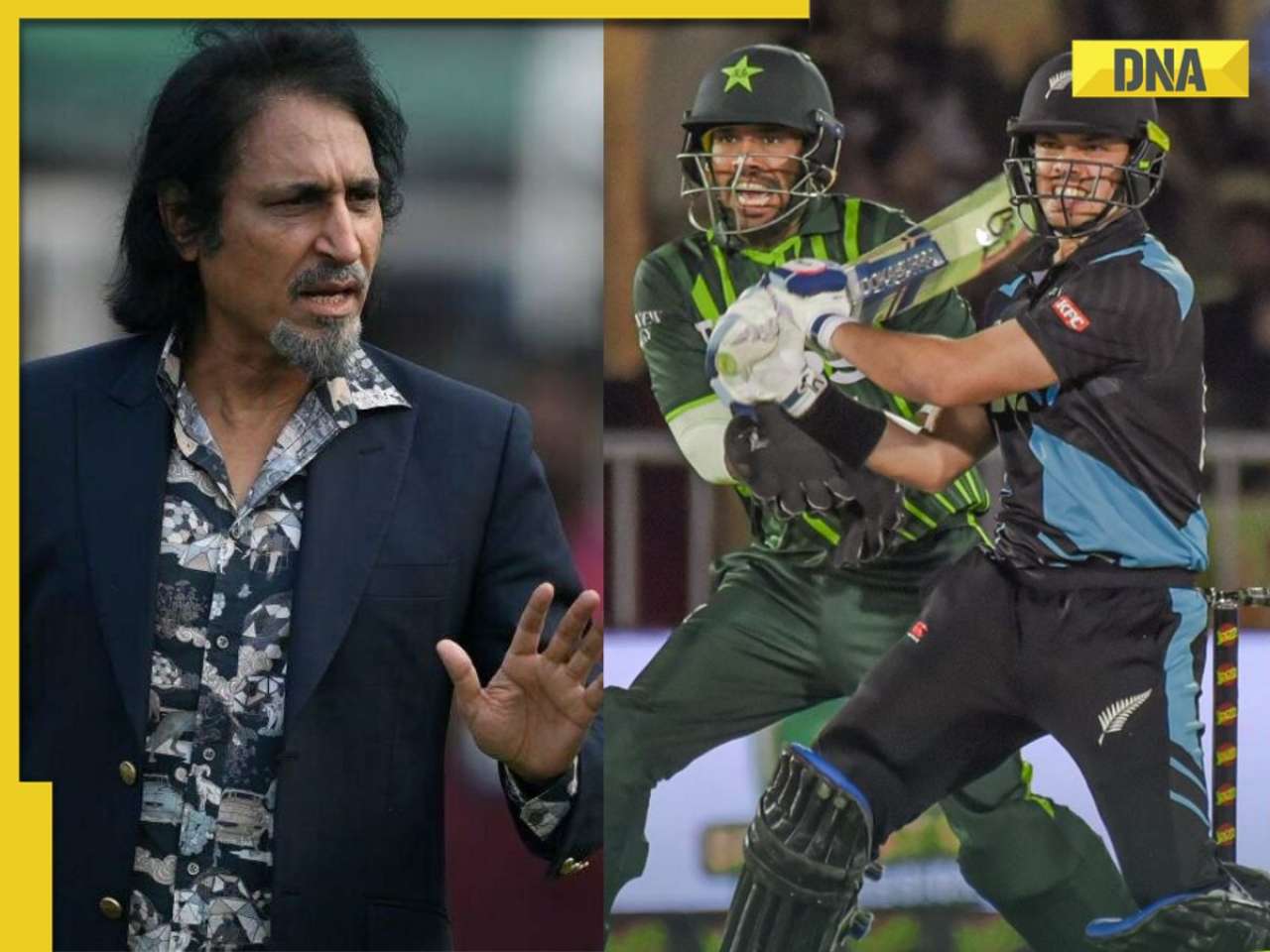

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

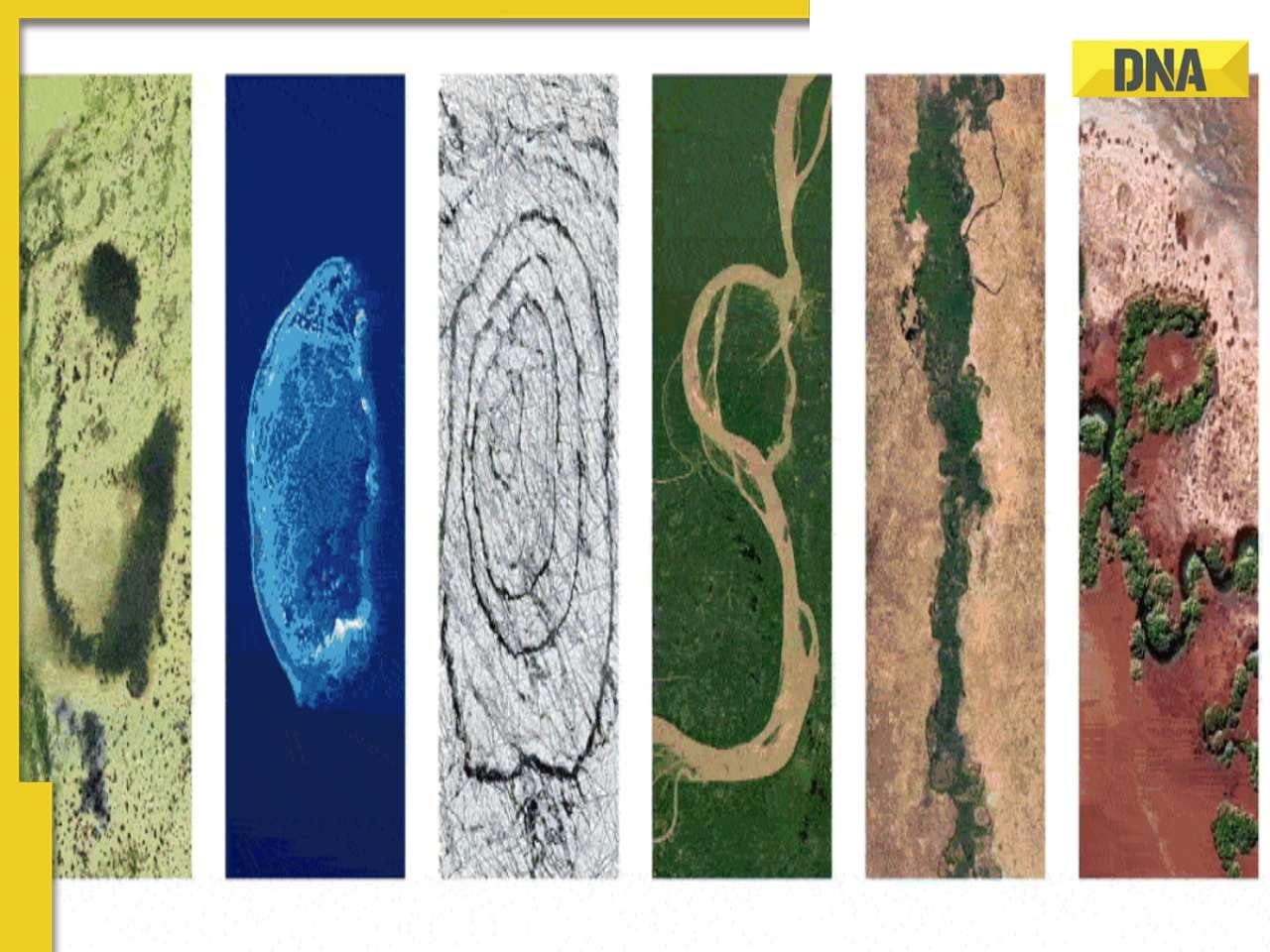

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)