In column after column, book after book, Khushwant Singh wrote about himself, laying bare cosy details of his life, his marriage, his wife, sex, the many women he bedded or wanted to bed, his penchant for his evening peg, emphasising the many ways he'd transgressed conventional or moral sensibilities.

In large part, this reputation that Khushwant had was a self-constructed myth, a literary device that many successful columnists have used before him, of creating a persona that was part truth, and large parts fiction.

For Khushwant, ironically, was a really nice man to know — notwithstanding an anthology of his best works being titled Not A Nice Man To Know — a gentleman of the old school, a man, his friends remember, of extraordinary generosity and zest for life; eccentric, no doubt, but also extremely disciplined and dedicated to the life of letters he'd chosen for himself. Stories abound of each of these traits among his friends and even people who'd met him just a few times.

dna correspondent Iftikhar Gilani remembers the elaborate lunch that Khushwant, then well into the 80s, laid out for him and his family in 2003, after his release from Tihar Jail, where he'd been incarcerated under the Official Secrets Act (the case was withdrawn by the government). "We sat with him for over two hours and he spoke to my children, my wife, even gifting her a book on butterflies and birds that he signed," Gilani remembers.

Many such tales of his generosity spring up almost accidentally through his writings. For instance, one article on the people he respected and admired has a delightful anecdote about how he lent Manmohan Singh Rs2 lakh in 1999 so he could hire taxis for his election campaign in south Delhi.

It's instructive to know that the man, now facing all round flak at the end of his second term as prime minister, went back to Khushwant days after he lost the election and returned the money — he hadn't used it, he said.

This anecdote, like so many others involving Khushwant, underlines one other thing — how pivotal he was to Delhi's power circuit, even after he'd long ceased to be an active player either as a politician, or a journalist. His influence was not just because he wrote a very popular weekly column in a widely read newspaper in town or that his father Sir Sobha Singh built large parts of New Delhi.

Malvika Singh, in her recent book on Delhi, Perpetual City, uses the term 'First Families of New Delhi' to describe Khushwant's family — and in a very real sense, it was. But over time, the family's advantage of being an early arrival was greatly expanded and cemented through long friendships with mates from school and college, professional connections and acquaintances.

Not that the generosity was not tinged with an eye for the petty ridiculousness of human behaviour. For instance, in Women and Men in My Life, he writes about how Shiela Ram, the wife of industrialist Bharat Ram of Delhi Cotton Mills, made a long-half-hour call from his flat in Paris to her husband in England — those were the days of prohibitively expensive international calls.

When she'd finished, she turned around and said, 'I would like to pay for the call but I know you won't let your sister pay for it.' "The brother-sister business cost me dearly," Khushwant comments wryly, recounting another instance when she picked up some old Mughal miniatures from his house saying, 'If you are my brother, you give this to me.'

Khushwant wrote about women a lot, and he knew some of the most interesting women of the past half-century. It's easy to accuse him of misogyny but, to be fair to him, he wrote about women as he did about men, with an unsentimental clear-sightedness that pierced through carefully constructed vanities. Take his much-maligned piece on Amrita Sher-Gil whom he'd met in Mashobra, where she lived and where his parents kept a house: "...she proceeded to tell me why she had come to see me. They were mundane matters....She wanted to know about plumbers, dhobis, carpenters, cooks, bearers, etc., she could hire in the neighbourhood. While she talked I had a good look at her. Short, sallow complexioned, black hair severely parted in the middle; thick sensual lips covered with bright red lipstick; stubby nose with black-heads visible."

His life was high drama. Or perhaps it seems so from the way he narrated it, in the confessional mode — with himself as, sometimes, its protagonist and, sometimes, bemused spectator.

Honesty — it was a byword for Khushwant's oeuvre, and he turned the cold light of truth with as much uncompromising brutality on himself as he did on others. In his book, Absolute Khushwant, he writes, "I've been with many women over the years. I've never worried about infection or sexually transmitted diseases. You don't think of all this while making love. You just go for it", etc. But that's quintessentially Khushwant — full of contradictions, and yet honest, in a bluff, earthy way.

It was evident in his avowed agnosticism, which did not, however, detract from his keen enjoyment of the shabads. He also wrote three highly-regarded volumes on Sikh history. But when it came to politics, the apparent contradictions of his views got him into controversy. His differences with Indira Gandhi and LK Advani are well known. He began on good terms with them and then turned against both — the former over the desecration of the Golden Temple in Operation Bluestar and the latter over the rath yatra that unleashed a fervour of religious fundamentalism. Even his views on the Emergency bespeak a curious equivocation. Khushwant, then editor of Illustrated Weekly of India, was perhaps the only editor to speak out in favour of the Emergency. However, in later life he wrote that he had "no idea then that it could and would be misused and abused".

The one thing he continued to be steadfast about, perhaps, was his admiration for Sanjay Gandhi, however much it isolated him among his fellow liberals. "He could be a real charmer. He had been good to me.

He put me in Parliament. Even Hindustan Times — it was he who called up Birla and told him to give me the editor's job," Khushwant wrote in 2010.

It takes a certain courage of conviction to make such an admission. And courage was the quintessential flavour of the legend that was Khushwant Singh.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

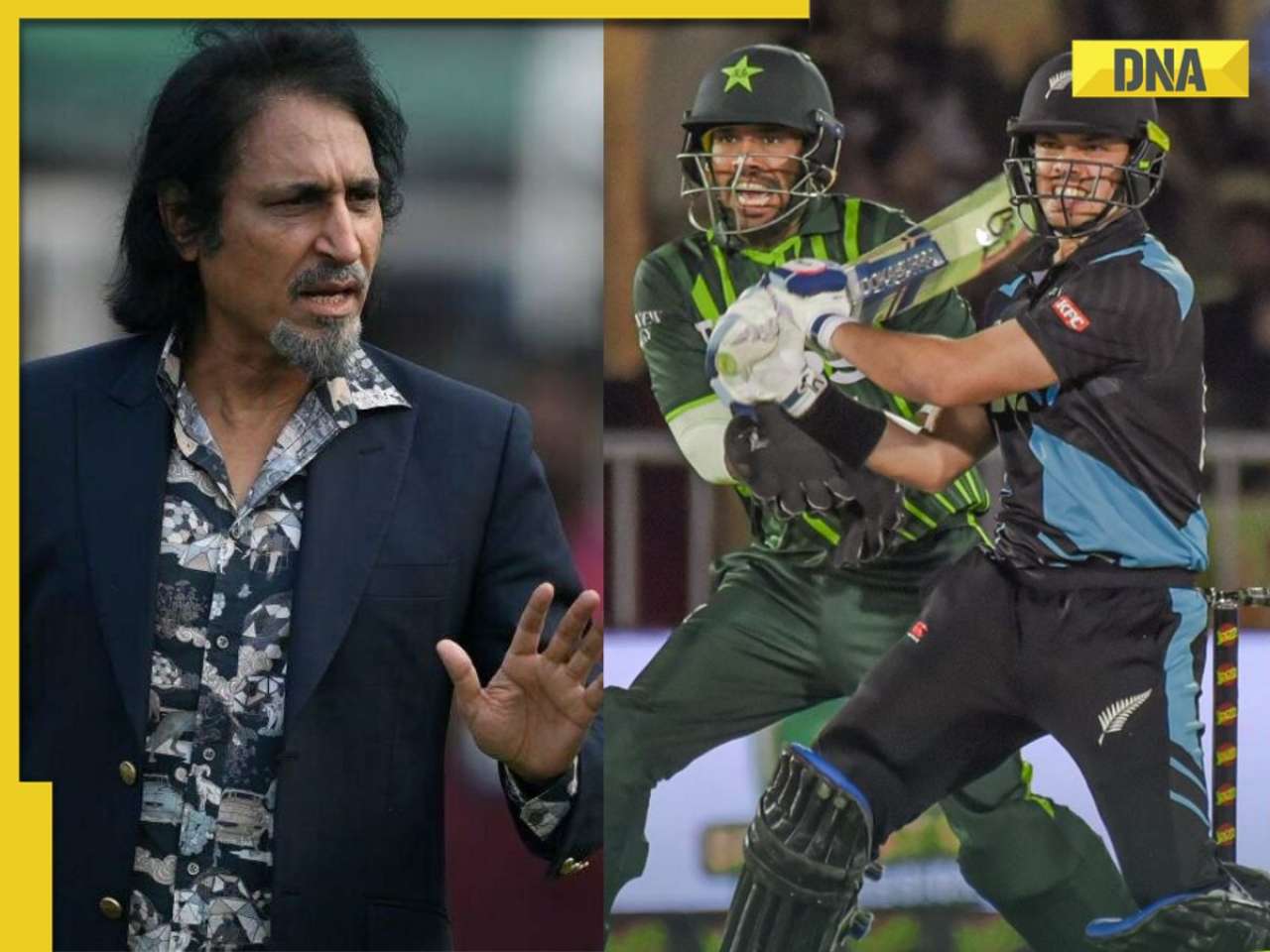

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

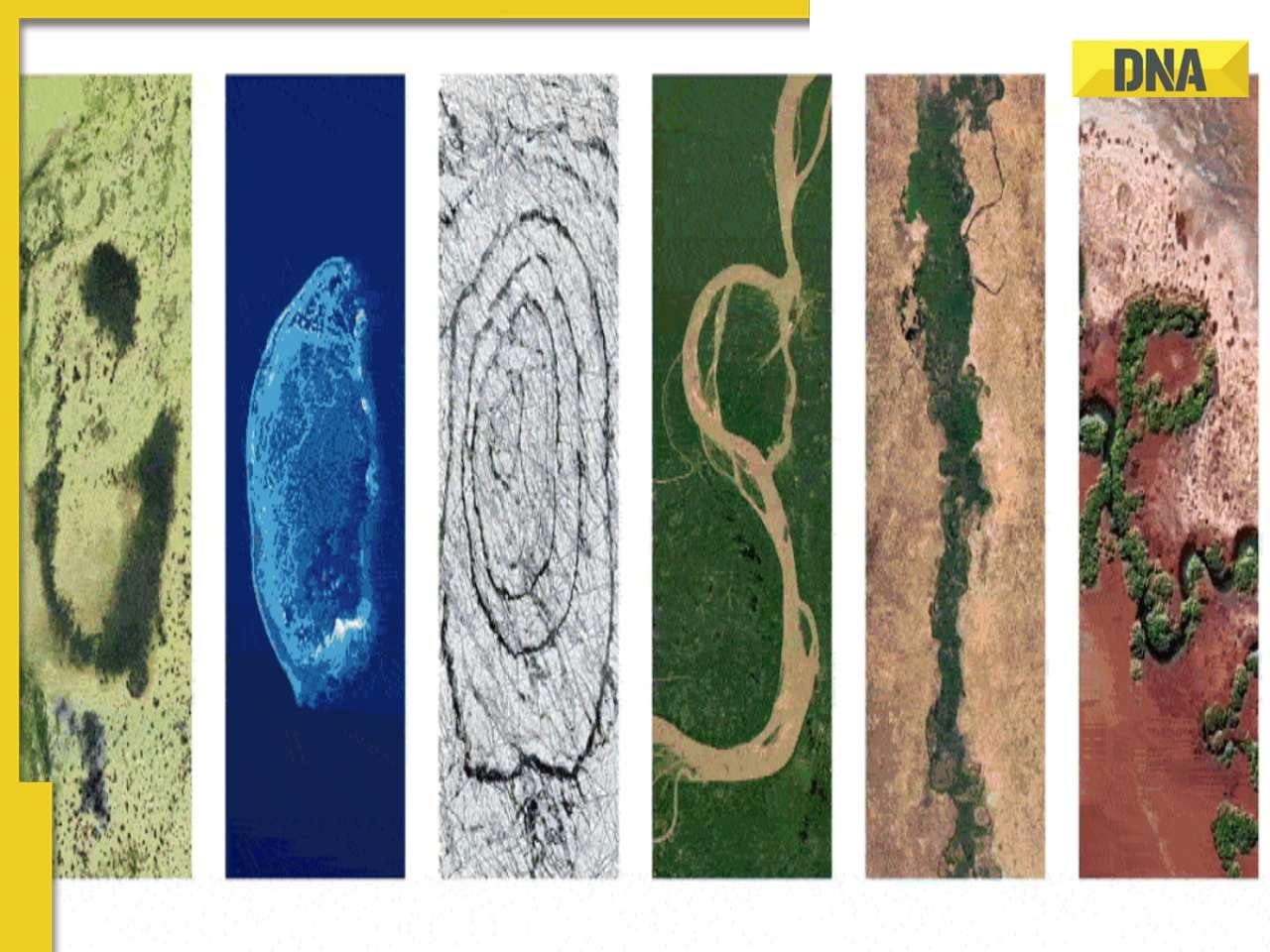

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)