The challenge for makers of fine Scotch whisky is to be innovative while at the same time staying rooted to the tradition that is their biggest selling point. Playing around with the casks in which whisky is aged can be one way to do this.

The whisky creation team of any iconic distiller in Scotland has to perform a fine balancing act. They can’t afford to dilute their brand and yet neither can they let it go stale. So they innovate just that much to produce a little twist every now and then. Most of these twists have to do with the cask in which the whisky is aged, because it’s the wood that accounts for 60% of the flavour of a whisky, according to David Blackmore.

He should know, because he works off and on with the creative team of Glenmorangie, makers of some of the finest single malts to come out of

Scotland.

To show me what he meant, he talked me through four malts, all clearly related to one another, and yet each one distinct. The first to be sniffed and swirled about on our tongues was the aptly named Glenmorangie Original. This had simply been aged 10 years in casks made of White American Oak, which had previously contained American bourbon.

What? A premier Scottish distiller using hand-me-down American casks?

David assures me this is by design. Apparently the sourmash that gets turned into bourbon in these leased out casks takes out the harsher tannins from the highly porous white oak. Two or three years of this and the casks are ready to impart their vanillins and other mellowed flavours to their new Scottish occupants.

If bourbon provided the starter, it’s wine that the creative team turned to for some divergent finishes to the original single malt. The second snifter I picked up, for instance, had the Glenmorangie Quinta Ruban. This one had been matured a further two years in barrels already used for Portuguese port wine, giving it a sweeter, richer flavour than the original, and a darker hue too.

Similarly, the Lasanta in the third snifter lay in American white oak for 10 years before being poured into Spanish sherry casks. The result was just that little bit spicier and less fruity than the Quinta, which made this my pick of the evening. The last one was called Nectar, because it had been extra-matured in casks treated with a dessert wine from Sauternes in France.

A lot of trial and error went into finding the right wine casks which would enhance the flavours of the single malt without corrupting its essence.

Not all experiments have happy endings. In fact very few do. David remembers with particular distaste a Brazilian cherry wood that was once tried as a substitute for the American white oak. “I realised why we use oak. The whisky that came out of that cherry wood cask smelt and tasted just like boot polish,” said David. Glenmorangie Cherry Blossom, they could have named it, but of course it never got bottled.

What next? Over our second round of malts at Tote on the Turf in Mumbai, David and I started talking about the Japanese single malts that were carving out a niche in the global market with their distinctive flavours comparable to the best from Scotland. They use Japanese oak, which is also very good for maturing whisky, David explained, and a light seemed to come on in his head. What if Glenmorangie manages to bring out the best of American oak and Japanese oak in its whisky?

David dreams of the day when, as a retired gentleman, 12 to 15 years now, he would be able to raise a toast with a whisky of his own creation. Well, if it has any Japanese oak in it, he’d better be raising that toast to me.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

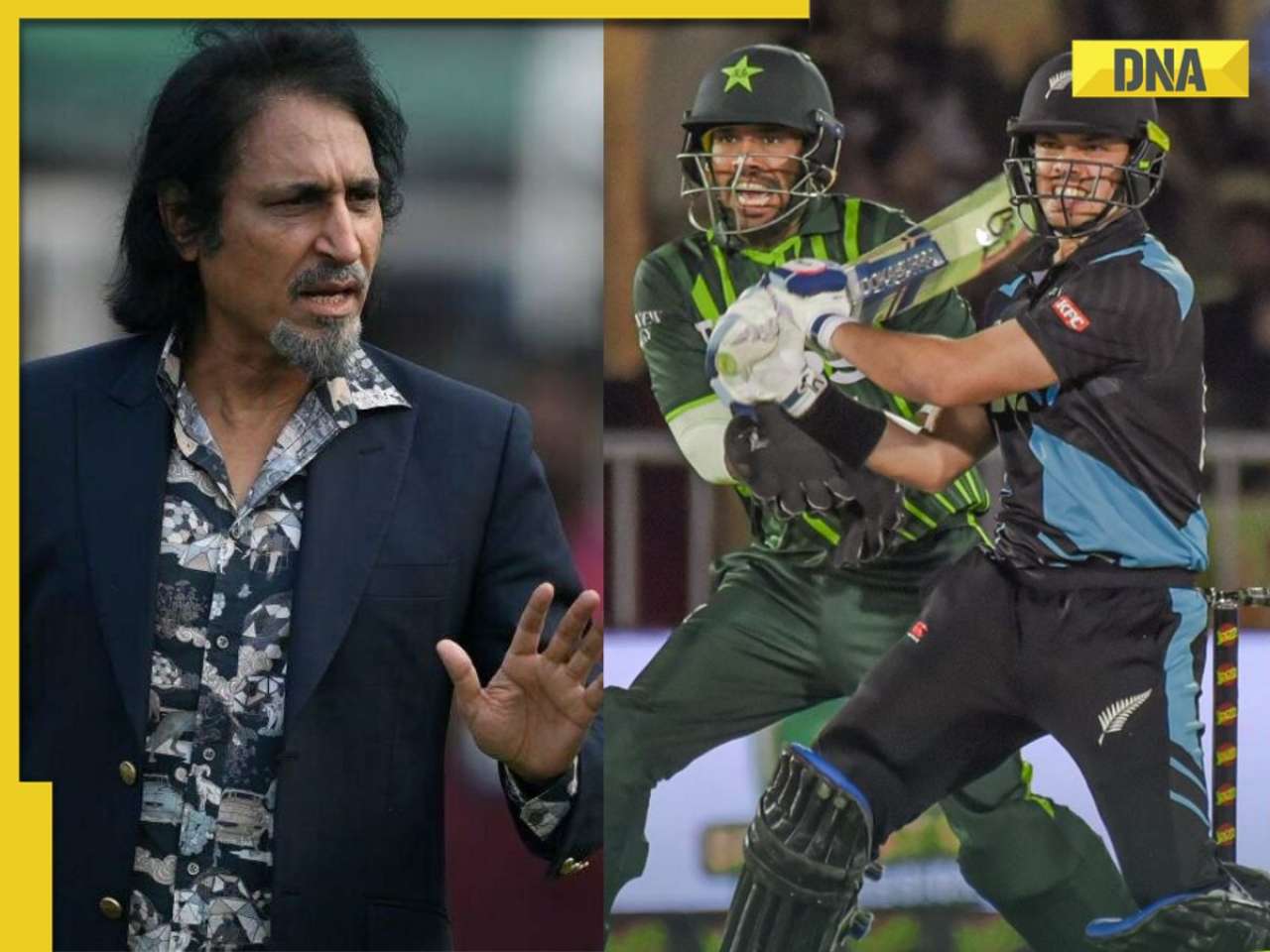

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

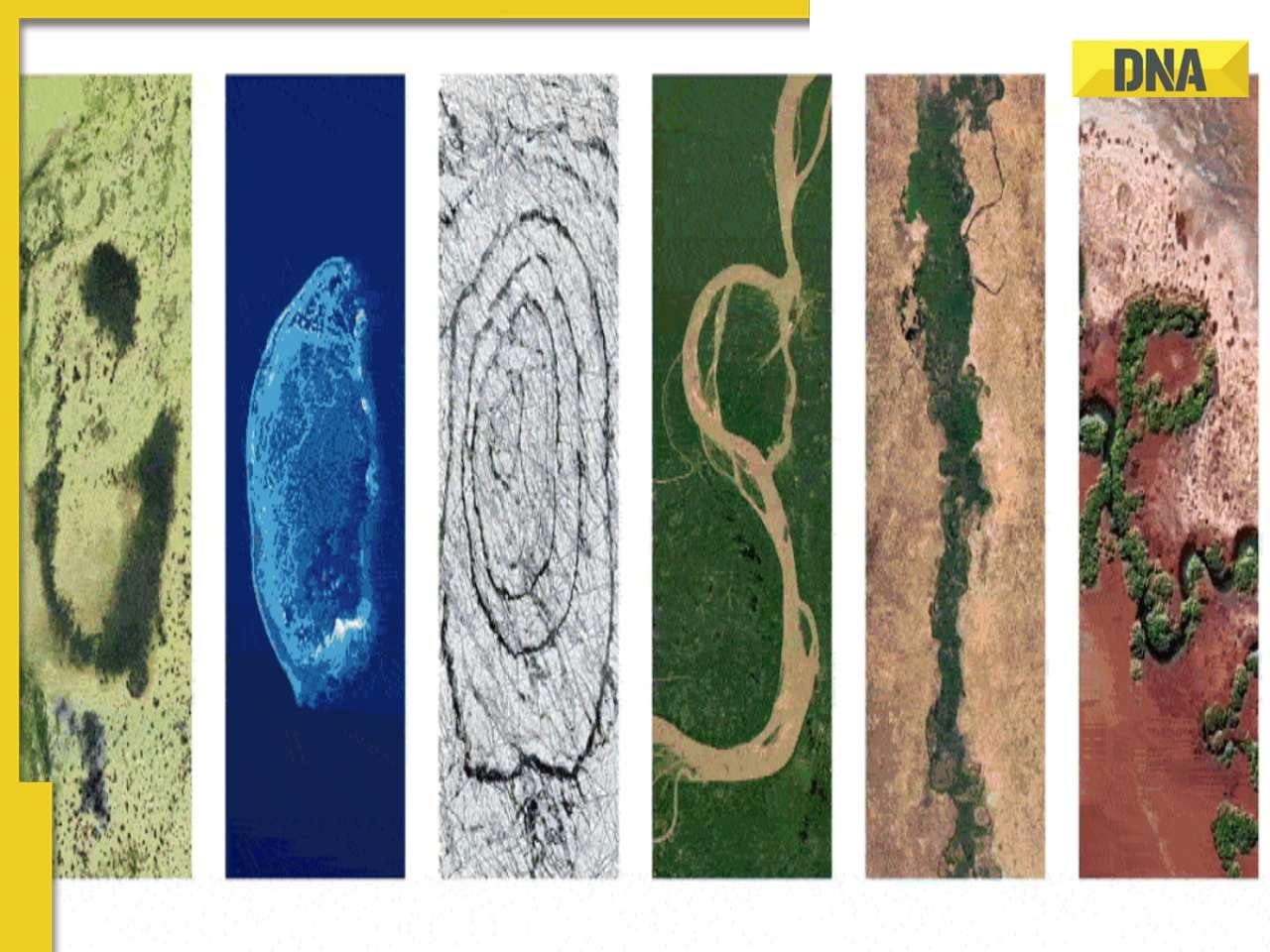

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)