A film on the ancient Jain practice of Santhara, or death by starvation, puts the fundamental conflict between religious rights versus the law at the forefront of debate. Is it suicide or soul cleansing, hoary tradition of ritual murder? Should a modern, secular state intervene? Yogesh Pawar examines the many legal and ethical dimensions of the issue

A steady drumbeat, heartbeat or simply the lashes of a whip? Its none of these but the waving of improvised paper fans, fanning a gnarled, emaciated septuagenarian. Reduced to just skin and bones, Sadhavi Mainibai can be heard breathing through her mouth, her eyes struggling to blink. This disturbing visual of Mainibai’s Santhara or Sallekhana - the controversial Jain practice, where a person gives up food and drink abstaining till death by starvation - stays with the viewer long after the 25-min documentary is over.

Reel vs real

This winner of the best script award at the recently held Bangalore Shorts Film Festival-2015 by Mumbai-based journalist-filmmaker Shekhar Hattangadi has brought the focus sharply onto this religion, law and constitutional secularism intersect. Its brought vigour to the churn in the ongoing debate over the centuries-old practice around since Lord Mahavir, the 24th and last Tirthankara who established the current tenets of Jainism in 400 BC. Over the centuries, thousands of his followers have embraced this feature of Jain orthodoxy.

But what about a subject many call “morbid” could have attracted any film maker? Hattangadi, a visiting faculty at two Mumbai law colleges explains, “Santhara for me is a classic example of the challenge that all faith-based societies face as they adopt modern, secular norms of governance, and the challenge is to reconcile individual freedom and personal liberty as well as a minority community’s religious rights on the one hand and, on the other, with the need for state intervention in matters of religion,” and adds, “While my film explores dimensions of this law-religion conflict by focusing on the spiritual, ethical, medico-legal and sociological aspects, I'm essentially interested in what happens when a traditional religious practice/ritual violates modern law?” He emphatically underlines his neutrality of approach. “This is the reason why I have not only interviews of litigants and their representatives involved in a PIL calling for a ban on the practice, but also legal luminaries on the other side of the debate apart from religious and community leaders.”

Abuse & coercion?

Despite its historical and religious significance, Santhara has of late come to face opposition by activists who demand its abolishment citing abuse and coercion. As someone responsible for the petition in the Rajasthan High Court, human rights activist and Jaipur based lawyer Nikhil Soni, should know. A native of Churu district in Rajasthan – with the reputation of the world’s Santhara capital for its highest per capita incidence of the practice in recent history - Soni says for years he quietly watched many such fasts-unto-death.

That was till September 2006 when Soni heard that one, Bimla Devi was being coerced into Santhara by her family. “Diagnosed with terminal cancer, the elderly Bimla Devi was too weak and depressed to protest as her relatives went about publicly announcing ‘her decision’ to undertake Santhara. And, in her final hours, when Bimla Devi began screaming in a last-ditch effort to get food and water, her cries were drowned out by loud bhajans sung to the accompaniment of high-decibel percussion.”

He remembers being shaken to the core. “Bimla Devi’s case convinced me that Santhara is, suicide masquerading as a religious practice wrapped in the mantle of hoary tradition. At its worst, Santhara came across as nothing but ritual murder, devised to rid a family of the economic burden of caring for its elderly who were seen as burden on the family budget.”

As he unsuccessfully tried to get the police to save Bimla Devi, he resolved to scale up his fight to save others from what he calls “being sacrificed” in the name of Santhara. “I filed a writ petition against the practice in the Rajasthan High Court calling it ‘a social evil’ that should be deemed an act of “suicide” — and therefore illegal — under Indian law. My petition demands that practitioners of Santhara be prosecuted under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code for ‘attempt to commit suicide’ and their supporters — who encourage it by venerating them as ‘spiritually elevated’ beings — charged with abetting this crime.”

Community Support

Community insiders place the conservative estimate to about 200 Santharas every year in India, which the 2001 census says has 4.3 million Jains. Although many insist though the Jains in India are actually between 6-8 million, many end up being counted as Hindus due to ignorance or supremacist homogenisation.

These numbers indicate how Soni’s petition has pitted him against the might of one of the wealthiest communities in India with sharp battle lines as both camps are unwilling to budge even an inch in their argument. “While Soni’s petition invokes Right to Life under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, the Santhara advocates, interestingly use the same Article to argue their side,” smiles Hattangadi. “The Right to Life, they argue, is meaningless without the corresponding right to stop living or the right to die. The same Article, they underline, also grants a person the right to personal liberty in such matters.”

Many like Jain studies scholar Manish Modi actually think that the hullaballoo over Santhara has more to do with larger right-wing Hindu plan to homogenise all minorities. "They have done this to all minorities and are trying the same with the Jain community too. The huge majority which swept in the current dispensation to power in the general elections last year has only emoboldened them."

Stances like these have been bolstered considerably by the active support of retired High Court judge Pana Chand Jain who not only seeks the protection of at least three other constitutional provisions, but also the endorsement of an international covenant. In his interview in the documentary he dwells on Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution which allow followers of all faiths to freely profess, practise and propagate their religious faith; and the freedom to manage their religious affairs. “Mindful of the country’s ethnic and cultural diversity, Article 29 guarantees citizens with a distinct culture, the right to conserve the same,” he points out and adds, “Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights — of which India is a signatory - says: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; [and the right] to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

Judiciary thinks otherwise

As if this weren’t complicated enough, the judiciary thinks very differently on this issue. While Santhara followers evoke the Constitution and international covenant, Soni has the weight of judicial opinion firmly on his side of the right-to-die debate {Maruti Shripati Dubal v State of Maharashtra (1986) and P.Rathinam v Union of India (1994)} which respectively held that “if destruction of one’s property or its deliverance to others for a cause or no cause is not an offence, there is no reason why sacrifice of one’s body for a cause or without a cause or for the mere deliverance of it should be regarded as an offence” and that Sec 309 of IPC was “unconstitutional and hence void.” This ruling by a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court ruled in Smt Gian Kaur v State of Punjab (1996) that “the right-to-life is a natural right embodied in Article 21, but suicide is an unnatural termination or extinction of life and therefore incompatible and inconsistent with the concept of right-to-life.” Emphasizing the sanctity of human life, the Court, in over-ruling both Dubal and Rathinam, was categorical that “by no stretch of imagination,” can “extinction” of life be read to be included in “protection” of life.

All eyes are now on the Rajasthan High Court. Will it accept the Supreme Court’s precedent in Gian Kaur and outlaw Santhara? Will such a decision ‘hurt’ religious sensitivities of nearly 6 million practising Jains worldwide, for whom the centuries-old ritual holds a pride of place among their sacred traditions? Justice Jain seems to have already anticipated this eventuality. He argues, “Santhara can’t be called “suicide” by no stretch of imagination. It is no where remotely an act of extreme desperation fuelled by anguish.”

The Christian view

“A Christian sees the human body as a God-given ‘temple of the human soul’ and hence beyond the realm of wilful and deliberate destruction, a devout Jain views that same body as a ‘prison of the human soul,’ the fulfilment of whose needs corresponds to the accumulation of bad karma,” points out Jain who quickly adds, “The Indian Penal Code, which forms the bulwark of criminal law in India, was incidentally drafted by Lord Macaulay, a devout Christian.”

Others like Digambar Muni Amoghakirti of the Nandishvaradvipa Jain Mandir in Mumbai’s far northern suburb of Borivali points out how for every 100 who approach him for undergoing Santhara only 4-5 qualify. “The person has to be willing to relinquish food and drink voluntarily after calm introspection, with intent to cleanse her/himself of karmic encumbrances and thus attain the highest state of transcendental well-being.” His senior Muni Amarakriti too says that the person seeking Santhara should have his family back the decision. He said he goes by prescribed signs in Jain scriptures. “If a person has blackening of tongue and nails, if the ear lobes are darkening and feel cold to touch, if the person can’t see himself beyond his chest, then we know,” he said remembering a case from last week. “He showed all these signs but said he is diabetic and can’t give up food. I told him to get rid of the idea of taking Santhara and pray instead.”

This doesn’t wash with Soni who likens the practice with Sati. “Most of the ‘victims’ are women — elderly widows with relatives keen to see them gone,” he charges.

Celebrating Santhara

A charge denied vehemently by Raju Baid the grandnephew of Delhi-resident Suvatidevi, 69 who breathed her last after four days without water on July 4th. “Why should we be sad? We respect and celebrate her decision to depart on her own terms after cleansing her soul,” Baid insisted, “In choosing to go the way she did, she has brought name and fame to our family.”

Santhara-supporters also baulk at the idea of any comparisons with the hunger strikes by Mahatma Gandhi during the freedom struggle, activist Medha Patkar during her agitation against anti-people, pro-dam government policies or even Manipuri civil rights and political activist Irom Sharmila who has been off food since November 2000 demanding a repeal of the draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). “Those are politically-motivated decisions to take on the state or political foes,” underlines Muni Amoghakirti. “The Santhara seeker doesn’t want anything. S/he is at peace. He doesn’t want to live nor does he seek death.”

While writ petitions, by their very nature, tend to jump the line in court ahead of regular suits, many have expressed dismay at the slow progress of the anti-Santhara petition. Many feel the court fears that legitimising Santhara would open the proverbial Pandora’s box. “Not only will this give the pro-suicide lobby a handle, but queer the pitch further for the embattled Section 309 (Attempted suicide) of the IPC,” points out Hattangadi who adds, “Any ruling against the practice would, on the other hand, mean re-looking at some key Articles of the Constitution relating to religious autonomy.” According to him, “Nikhil Soni v Union of India & Others will undoubtedly be a landmark case.”

But this isn’t the first time an Indian court will decide between conflicting constitutional provisions concerning religion. In 1958, the Supreme Court in M H Qureshi & Others v State of Bihar took on the issue of a ban on cow slaughter [Art 48] impinging on Muslim festivities during Bakr-Id [Arts 25, 26] and on the fundamental right of butchers to carry on their trade [Art 19(1)(g)]. Only this time, the issue is decidedly more sensitive, and its consequences far more profound: it involves the extinguishment of a human life.

In these frenzied times of religious intolerance and knee-jerk opportunism, all eyes will be on the bold judge who wouldn’t flinch in the line of duty.

![submenu-img]() Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins

Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins![submenu-img]() Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'

Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'![submenu-img]() India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat

India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat![submenu-img]() Vellore Lok Sabha constituency: Check polling date, candidates list, past election results

Vellore Lok Sabha constituency: Check polling date, candidates list, past election results![submenu-img]() Meet NEET-UG topper who didn't take admission in AIIMS Delhi despite scoring AIR 1 due to...

Meet NEET-UG topper who didn't take admission in AIIMS Delhi despite scoring AIR 1 due to...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Tanvi Hegde? Son Pari's Fruity who has worked with Shahid Kapoor, here's how gorgeous she looks now

Remember Tanvi Hegde? Son Pari's Fruity who has worked with Shahid Kapoor, here's how gorgeous she looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Kinshuk Vaidya? Shaka Laka Boom Boom star, who worked with Ajay Devgn; here’s how dashing he looks now

Remember Kinshuk Vaidya? Shaka Laka Boom Boom star, who worked with Ajay Devgn; here’s how dashing he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

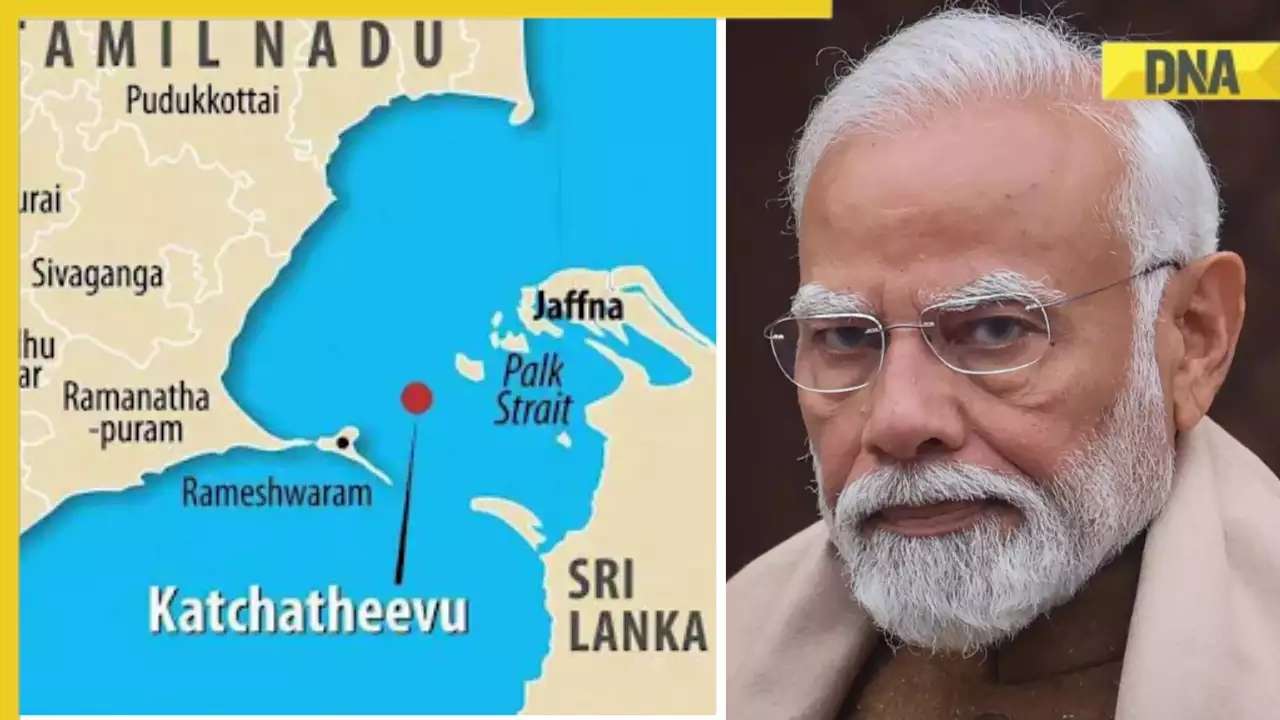

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Reason behind caused sudden storm in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur

DNA Explainer: Reason behind caused sudden storm in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur![submenu-img]() Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins

Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins![submenu-img]() Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'

Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'![submenu-img]() India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat

India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat![submenu-img]() This film has earned Rs 1000 crore before release, beaten Animal, Pathaan, Gadar 2 already; not Kalki 2898 AD, Singham 3

This film has earned Rs 1000 crore before release, beaten Animal, Pathaan, Gadar 2 already; not Kalki 2898 AD, Singham 3![submenu-img]() This Bollywood star was intimated by co-stars, abused by director, worked as AC mechanic, later gave Rs 2000-crore hit

This Bollywood star was intimated by co-stars, abused by director, worked as AC mechanic, later gave Rs 2000-crore hit![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

RCB vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Sunrisers Hyderabad ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Phil Salt, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 8-wicket win over Lucknow Super Giants

IPL 2024: Phil Salt, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 8-wicket win over Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Why are Lucknow Super Giants wearing green and maroon jersey against Kolkata Knight Riders at Eden Gardens?

IPL 2024: Why are Lucknow Super Giants wearing green and maroon jersey against Kolkata Knight Riders at Eden Gardens?![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Shimron Hetmyer, Yashasvi Jaiswal power RR to 3 wicket win over PBKS

IPL 2024: Shimron Hetmyer, Yashasvi Jaiswal power RR to 3 wicket win over PBKS![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)