It seems that the rich tradition of combining functionality and aesthetics is all but lost in the India of today. Yogesh Pawar finds out why in this requiem for the 'skills of India'

Towards the southern end of Worli sea face in central Mumbai is an installation of a huge laman diva, the traditional Maharashtrian lamp. The laman diva, said Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis while unveiling the logo of the first Make in India Week recently, has "great relevance in our culture as a symbol of auspicious beginning, peace, prosperity, growth."

But that wasn't why a busload of Japanese tourists stopped to take pictures last week — their cameras and phones were in fact positioned to capture the thick, ugly cable descending from the light pole across to power the CFC lamps atop the installation, which has been designed by Nitin Desai of Lagaan, Jodhaa Akbar and Devdas fame.

"We thought it was done deliberately and that the cable was part of the installation," laughed Futoshi Tajima, a Kyoto resident struggling with his limited English. The engineer with one of Japan's largest electronic majors kept gesturing to ask why the cable couldn't come from under the installation.

Embarrassing design malfunctions like this or even the fire at the Make in India cultural function that saw the stage reduced to cinders may be forgotten with the passage of time. But they have put the spotlight on the sorry state of craftsmanship and skills in a country that boasts of a rich tradition of perfection in the field for millennia, say experts.

Pradyumna Vyas, director of Ahmedabad's National Institute of Design (NID), is shocked. "Have you tried getting something basic as a table's broken leg repaired, a leaky washbasin fixed or the house painted?" he asks. "It's appalling how hard it is to find someone to do simple things. And expecting it to happen without a disaster or two, and getting both functionality and aesthetics right is like asking for the moon itself."

Isn't this the country that has architectural wonders like the Kailasa temple in Ellora near Aurangabad, the Nataraja temple at Chidambaram, the shaking minarets of Sid Bashir mosque in Ahmedabad and Agra's tourist magnet, the Taj Mahal? "The traditional craftsmanship used to be a familial legacy handed down to generations. Exceptionally skilled craftsmen enjoyed patronage of royalty and rich traders and this allowed them to singularly focus on bettering their craft. Artisanal quality that we sing paeans to comes from such support and patronage," points out Vyas.

Running crafts aground

Over 400 km away in Madhya Pradesh's Maheshwar town on the banks of the Narmada, where the matriarch queen of the Holkar family Ahilyabai brought weavers from Varanasi, Surat, Irkal and Chennai to start the local Maheshwari textile tradition, 60-year-old Arvindbhai Kumar says he wants to give up weaving. "None of my sons have learnt it fully. They mock me when I pester them. They say they'll earn far more working in garages or eateries. Though it hurts me that the family legacy will be lost, I see their viewpoint."

In the last month alone, three weavers have committed suicide due to debts. That Maheshwari and Chanderi saris sell for a fortune is not just ironical but also a tragedy. "Unlike earlier, when we sold directly to people, we are now forced to sell to traders, middlemen who have linkages with big emporia and designers. When there is such a big line of people in between, you can imagine what must trickle in. Any voice of protest is quickly stifled by the cartels who will boycott you. Many of our looms and workshops too are mortgaged to these very cartels."

Dignity of labour

Back in Mumbai, 600 km from Maheshwar, the disregard for dignity of labour finds an echo in Vile Parle. "People who go to Thailand and Bali bring back baskets and wicker work for which they are willing to pay big money in dollars. But here you should see how they will drive a hard bargain, denying me even the price of the material," says Jayantbhai Prajapati, who runs a small shop near the Cooper hospital. He cites the instance of a well-known filmmaker, who calls him to fix bamboo strip curtains every alternate year. "They own luxurious cars, have servants to take care of three dogs and live in a palatial bungalow in Juhu but refuse to pay me even Rs500 more than the rate charged two years ago. 'Bamboo ka hai na, sone ka nahin,' they say."

Sociologist-activist Tulika Das, who works in the Samata Nagar slum in Kandivali where Prajapati lives, says she's baffled by both the sheer injustice and the huge number of people against whom it is perpetrated by those in the same position a few years ago. "I've met people who work as drivers or peons with people whose lifestyles are rising rapidly. But that doesn't translate into proportionately fair raises for the people working for them," she laments. "Incidentally, these are the same people who quote the French economist Thomas Piketty's work on wealth and inequality to point out the difference in quality of life between them and the filthy rich."

According to Das, the middle class' apathy and its failure to recognise traditional skills as being equal, if not more important than the new ones, is unfortunate. When a weaver or diamond setter is not given the same respect as someone with a flair for software, it pushes the best people out of what they see as menial, thankless professions. "This vacuum is being filled by rejects who are not good at anything else like academics. Unwillingly forced into a job they detest, they can never bring an artisan's passion to it. This sets into motion a vicious cycle of shoddy work, negative feedback and poor pay, which a huge chunk of India's working population finds itself trapped in," says Das.

The mismatch between what is taught in academic courses and what is needed for employability only makes this more problematic. The findings of a 1999 study by Dr KC Datta (who headed TISS' Personnel Management & Industrial Relations department) had reflected that this had led to a lot of red faces and outrage 16 years ago. Today, the situation has worsened because the job market has changed drastically, says Datta. "Yet, look at how little what we teach children in school and college has changed."

Changing ecosystems

NID's Vyas, who is also member-secretary India Design Council, says even the timeline of events has a role to play. Grassroots ecosystems, where weavers, potters, blacksmiths and others were able to peddle their skills and wares within the village, worked perfectly for hundreds of years when everyone was interdependent. "In fact, Mahatma Gandhi envisaged this as the ideal that India should go back to ('India lives in her villages'). But by then, the clock had moved far ahead, especially after the industrial revolution when it all became about cheaper, faster goods, products and services. Since liberalisation, when we moved from being a manufacturing economy to a service-based one, the complete disconnect with the faceless woman/man at the end has only increased."

Whether it's at the grassroots level or the upper echelons, almost everyone agrees that the government needs to work more on people-intensive ideas than logistics, technology and money-intensive ones, which will only help further line the pockets of the rich. Das nails it when she says: "Till we figure that out, Make in India will never be written in the past tense. It'll remain something that only Alisha Chinai's done."

India unemployment Rate 1983-2016

Unemployment rate in India decreased to 4.90% in 2013 from 5.20% in 2012. Unemployment rate in India averaged 7.32% from 1983 until 2013, reaching an all time high of 9.40% in 2009 and a record low of 4.90% in 2013. (Unemployment rate in India is reported by the Ministry of Labour and Employment)

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

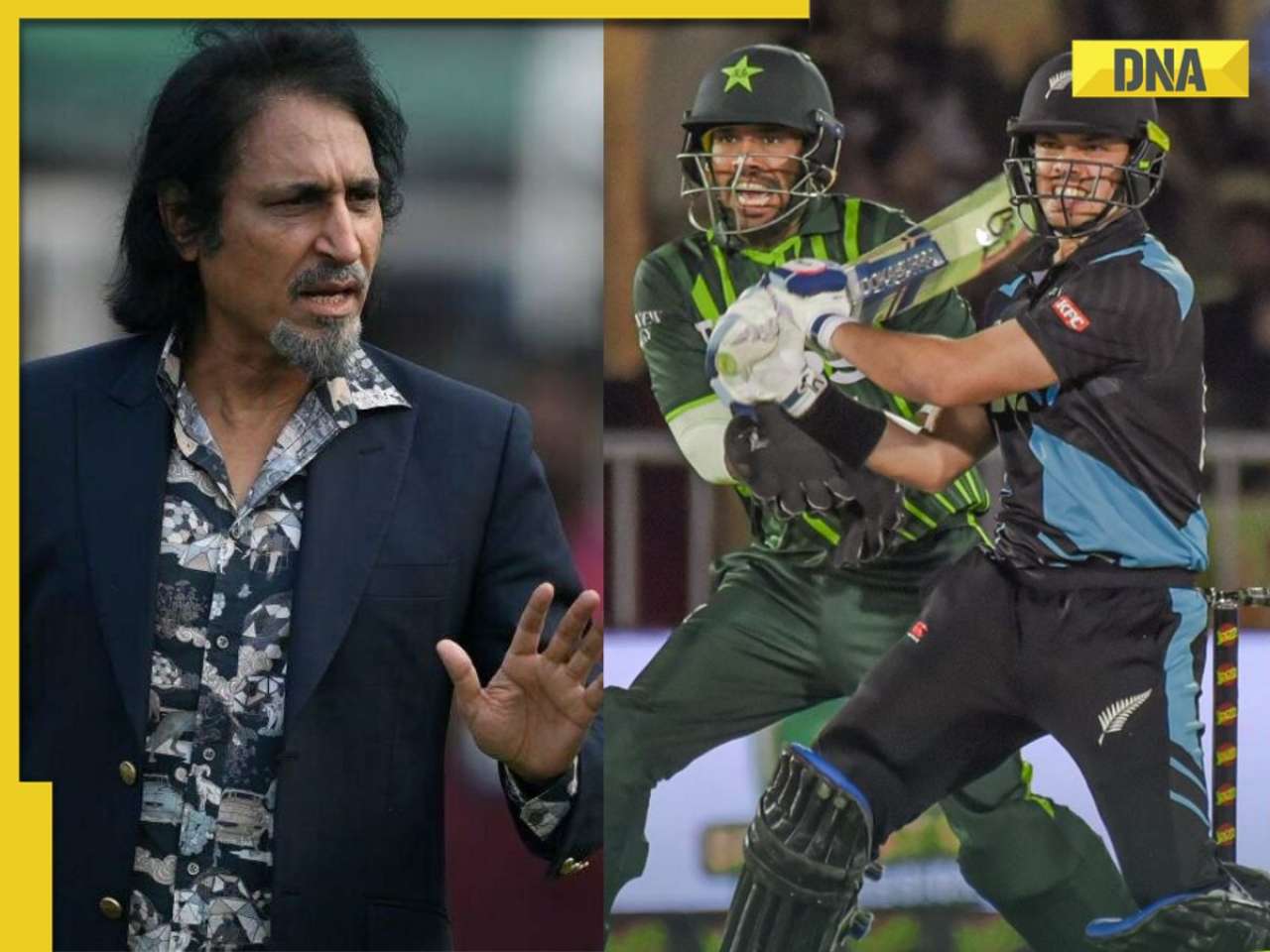

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

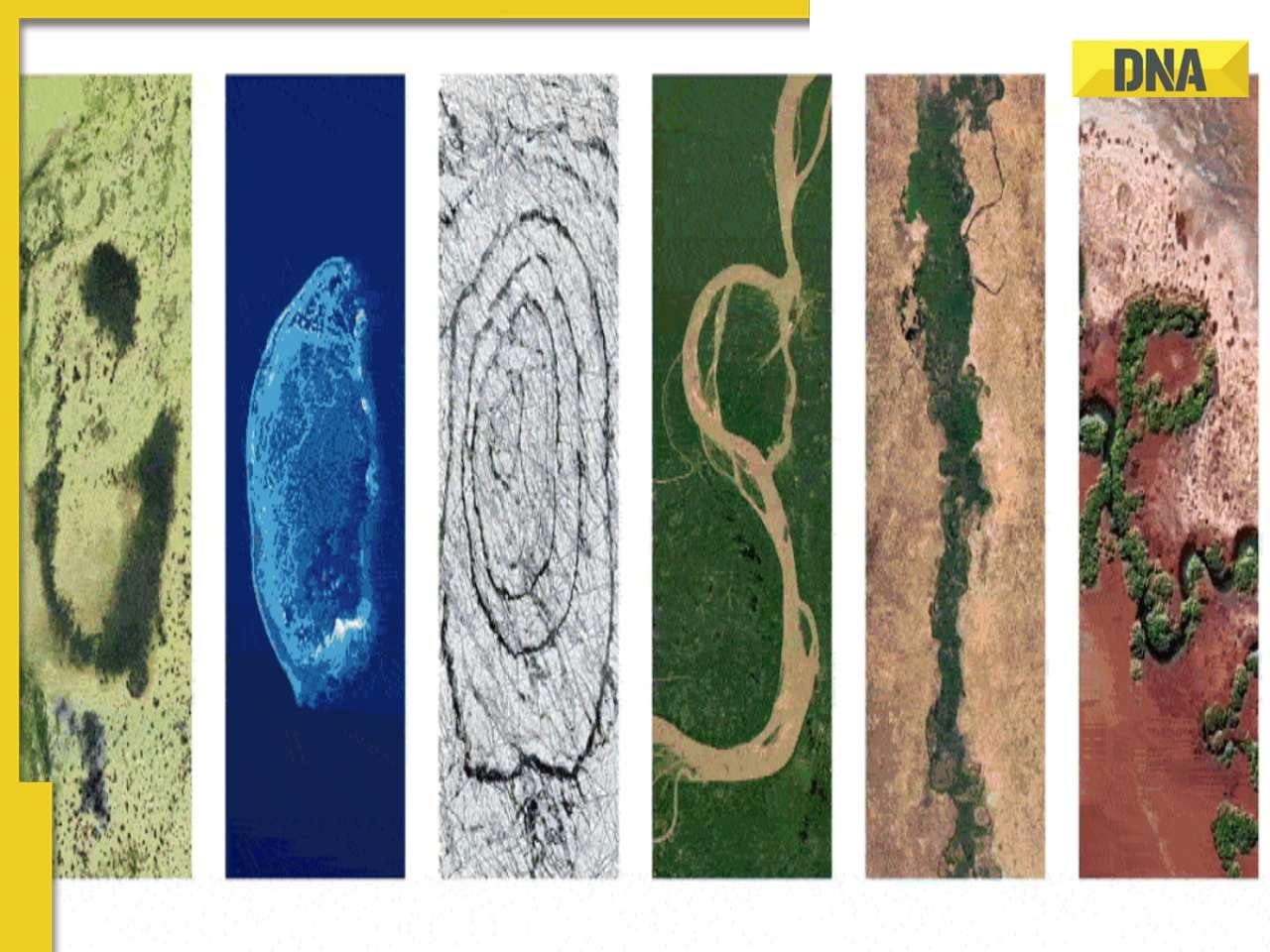

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)