As the debate about what pushes the young towards radicalisation gathers momentum with the rise of the Islamic State, Yogesh Pawar speaks to young Muslims who are shunning not just radicalisation but the religion itself.

Fakeer Mohamed Althafi speaks so softly that you have to strain to hear him. The 32-year-old physiotherapist from Tamil Nadu says he’s been an introvert since childhood and loves blending into the background. At the bachelor’s pad which he shares with a trio of peers in midtown Mumbai, he insists that no more details about his address be given. “If someone found out where I lived,” he explains, “they could come attack me or worse.”

And no, Althafi is not a controversial political figure/activist. So, considering he admits to being no more than “a regular bloke”, what is he so scared of? Just this -- five years ago, this native of Ramanathapuram told his family that he no longer believed in the fundamental tenets of Islam. “I stopped being a believer. I know the word apostate sounds funnily anachronistic, but I’m not saying this lightly.”

Isn’t that borderline paranoid? “I wish it were,” Althafi smiles wryly. He recalls how T J Joseph, a professor of Malayalam at Newman College in Kerala’s Thodupuzha town had his hand cut off at the wrist as punishment for allegations of blasphemy. As the radical fringe of organised religion becomes more vocal and extremist in its views, there are many other instances, cutting across countries. “The deadly assault on the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo, a French newspaper that satirised religion, or the hacking to death of several bloggers in Bangladesh (Ananta Bijoy Das in May, Washiqur Rahman Babu in March and Avijit Roy barely a month before that) for openly supporting atheism may seem far away, but the threat here too is very real and close,” says Althafi.

When he confessed his atheism to his horrified family, his eldest brother reminded him that the penalty in Sharia law for apostasy is capital punishment. His family was ready to forgive him if he remained Muslim. “They wanted me be a religious hypocrite. I can’t do that. I don’t mind the qawwalis, pathani suits, the biryani and the phirni but how could I pretend to follow a faith I simply didn’t feel.”

***

Over 2,000 km away, Selina Bi Sheikh of Motijil village in Murshidabad district of West Bengal is angry. It has been two months since she was stripped and brutally beaten allegedly for converting to Christianity. She doesn’t mince her words when asked if she minded being named. “Why should I be ashamed? Ask the local Muslim extremists who have resolved to ostracise me till I return to Islam that question,” she says firmly.

It’s almost funny, she says, that her opponents find a 54-year-old widow who lives with her two young sons threatening. “I’m not allowed to buy even soap or toothpaste from the local shop or the grocer.”

Though it means having one of her sympathetic neighbours fetch water for her from the village well, she says she will not give up Christianity. “Why can’t I choose?” she asks defiantly... a defiance which has seen several complaints registered against her at the Murshidabad police station for “disturbing peace and harmony.”

***

Sherbanoo, a 28-year-old Bohra banker from Pune, is being accused by her mother of doing the same to the family. “It has been nine years since I opposed the clergy in our mosque,” remembers Sherbanoo. “After my genitals were forcibly mutilated when 19 and this was sought to be given a religious rationale to keep me quiet and compliant, I developed an aversion for everything Islam. A brief stint at the Cardiff University on an exchange programme gave me the strength to tell the clergy what they’re practising is not Islam but unbridled

misogyny.”

Expectedly, what she calls “the loonies and their threats” came fast and thick. “What I hadn’t prepared for was the way they manipulated my parents and family. When my brother joined my father in beating me up for ‘shaming the family’, I left home and began living by myself.”

Doesn’t she miss family? “I do. See, in Islam you’re only part of the community group. There’s no individual identity. It is like one would be lost without the collective. Having found my independent voice, going back to my folks would mean becoming part of the same claustrophobic reality I've turned my back on.” She feels the creation of an umbrella organisation on the lines of the Council for Ex-Muslims of Britain would help a lot in reassuring others like her to come out.

Althafi, Selina Bi and Sherbanoo aren’t alone. Though the number of Muslim non-believers is on the rise, not everyone is leaving the religion. At a time when the radicalised are willing to travel across the world from as far as Britain and Australia to enrol as warriors of the Islamic State to kill non-believing kafirs (infidels), perhaps wisely so.

“The mob baying at the doorstep is not the biggest risk ex-Muslims face. Loneliness and isolation of ostracism from loved ones, the stigma and rejection prevents many ex-Muslims from going public with their apostasy,” says Dr Simon Cottee, author of a new book The Apostates: When Muslims Leave Islam.

A broader and long-standing interest in deviance and transgression saw Cottee - a faculty member of the School of Social Policy, Sociology & Social Research, University of Kent - research Islamic apostates. “From the perspective of Islam and many Muslims, apostasy is a profoundly deviant, since it involves a rejection of the very foundations of Islam. Apostasy is more than criticism; it is renunciation. And people of the faith take this personally since their belief in Islam is so intimately tied to their core identity. As one of my interviewees put it to me,‘People get very emotional about it. It’s not just that you’re criticising Islam. You’re actually criticising its very foundations and people take it as an attack on their identity, not just their belief’.”

“Attitudes need to change,” says Cottee. “There has to be a greater openness around the whole issue. And the demonisation of apostates as ‘sell outs’ by both left-liberals and reactionary Muslims must stop. People leave Islam. They have reasons for this, good, bad or whatever.It is a human right to change one’s mind.”

He further adds, “Because they had once known the ‘truth’, their subsequent rejection of it is all the more unsettling and confusing for true believers. ‘The apostate,’ wrote the classical Muslim jurist al-Samara’i, ‘causes others to imagine Islam lacks goodness and thus prevents them from accepting it. But that is not why apostates arouse disquiet among Muslims. That happens because Muslims find them confounding. Because if one person can be persuaded to leave Islam, then why not all?”

Touchy subject

Cottee admits it's a subject many avoid. “Few touch this subject, although there is a keen sociological interest in conversion to Islam. I think this reflects the liberal and radical biases of sociology. Sociologists don’t want to offend Islamic sensibilities by studying themes unsettling to Muslims – this could be one explanation for the neglect. Or maybe it’s because they fear being called Islamophobic. It doesn’t reflect well on sociology, which has become a moral and intellectual wasteland.”

This is echoed by others like Imtiaz Shams, who runs a group called Faith to Faithless, which aims to help Muslim non-believers speak of their difficulties. The 26-year-old’s strong YouTube presence and several of his well-attended talks at universities across the UK have left him at grave physical risk. “Nobody likes to be in the firing line, but I had to do this because no one else was.”

Like Shams, Pakistani-Canadian writer-musician-physician Ali A Rizvi who is working on his book, The Atheist Muslim, often gets trolled on social media for his views. "Is it extremists that are corrupting Islam, or is it moderates that are sanitising it?” he tweets, questioning the moderate Muslim who says s/he doesn’t believe in misogyny, murder, or homophobia. “Why then revere a book that endorses them?” he asks. “The dissident Muslim/ex-Muslim is always caught between the right's bigotry and the left's apologism.” According to him, it should be acceptable to criticise Islam as long as this does not amount to demonising all Muslims.

In fact Dr Cottee likens leaving Islam to the coming out for gays in countries where homosexuality is still criminalised. “The fight for the right to be recognised in both cases comes at the often prohibitive cost of shame, rejection, intimidation and very often, family expulsion.”

Those who disagree

Some like relationship coach and sensitivity trainer Altaf Shaikh question what he calls “notion” of apostasy. “I use the bigotry and intolerance against Islam to help fortify my faith,” says this Mumbai resident who survived the 1992-93 riots by the skin of his teeth. “These ‘apostates’ are taking the stand they do, because of ignorance.”

According to him, Islam is facing two crises from within and without. “The ill-informed radical voices tend to give their own twisted interpretation to scriptures and using that to justify everything from wars, misogyny to human rights excesses. On the other hand, there are those who are using this to further their ‘otherising’ agenda for Muslims. As the persecution and discrimination gets stronger to the point of vilifying an entire people, this has led to a backlash of sorts with misguided youth often becoming easily influenced by the shrill radical call-to-arms voices.”

Imtiyaz Jaleel, TV journalist-turned All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul Muslimeen MLA from Central Aurangabad in Maharashtra, echoes this sentiment. “The radicalisation among Muslims can't be seen in isolation. The negation of the community’s aspirations by both the saffron parties and the so-called secular ones is what needs to be seen along with that narrative.” According to him, “Asking questions from within the fold is understandable and can be welcomed. From without there is always the lurking suspicion of hidden agendas coming into play.”

Not only Islam

"While its true that apostasy continues to be criminalised by only 19 Muslim majority countries - 11 of which are in the Persian Gulf - Islam isn't the only one concerned with the phenomenon," explains socio-cultural historian Mukul Joshi. "This has been the case with all proselytising religions historically. Christianity too frowns on what the New Testament twice refers to as the 'wilful rejection of Christ by a practising Christian." According to him some of the human rights excesses in the past under the Vatican's watch had to do with apostasy. "Classically Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism welcomed apostasy and many of their canonical texts are replete with debates and arguments that support this," he explains and adds, "Unfortunately current times have seen hardening of stances all around with bigotry and intolerance becoming the dominant sentiment of our times. Its saddening that some political and religious outfits in these religions too are now beginning to talk of annihilation of non-believers."

He is quick to point out how often the denunciation of a faith itself takes on a zeal bordering on the religious. “The shrillness on the other side then only finds a match on this side too. Any real understanding will require the complete abandonment of the shrill by both sides. Only then can they talk and find a way of working with/around each other.”

Did someone say, easier said than done?

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

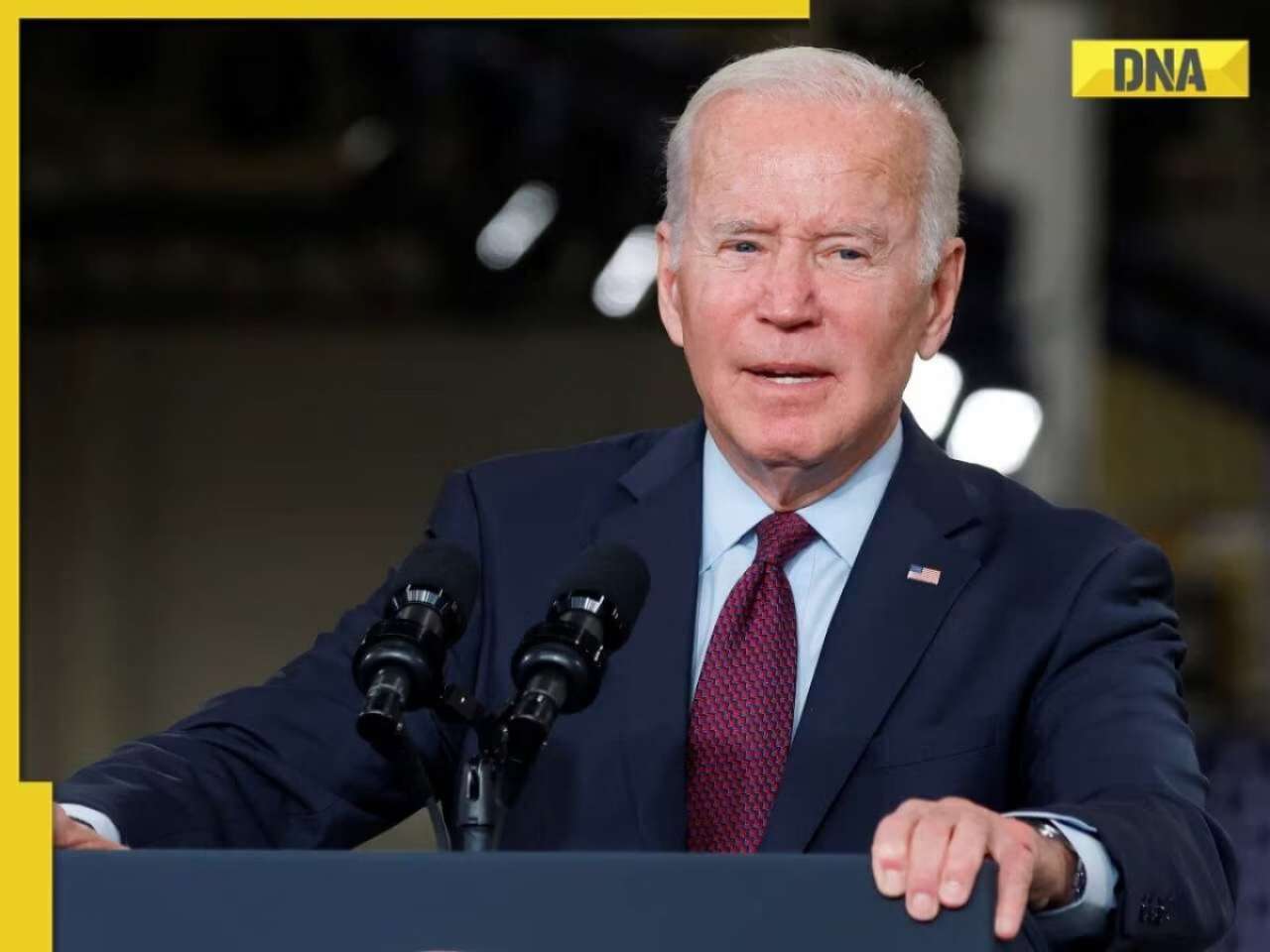

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)