That the Naval Mutiny was short-lived and has become virtually an unknown episode in the post-Independence era is a crying shame. It is, nonetheless, a remarkable story and that deserves a more prominent place in British-India history, writes Pramod Kapoor, as he walks us through the brief but fierce event

A few years after India's independence, Britain's former Prime Minister Clement Atlee was in Calcutta on a semi-official visit. During a banquet at the Governor's House, Justice PV Chakraborty, former chief justice of the Calcutta High Court, leaned across and asked Atlee how much impact Mahatma Gandhi's quit India movement had on hastening Britain's exit from India. Atlee's answer was "minimal,'' adding that it was the unrest in the Indian defence forces, particularly the mutiny by naval ratings, that forced them into leaving India earlier than planned.

For most Indians, that reference would be confusing. The mutiny they know about and recorded in the history books happened in 1857, and was called the Sepoy Mutiny. The one Atlee referred to took place in February 1946, in Bombay, and is a largely ignored and unknown event despite it being so serious in terms of the security threat it posed, involving 2,000 Indian naval personnel, the loss of some 300 civilian lives, and seizing of armories on British ships with their guns trained on such iconic structures such as the Gateway of India, the Taj Hotel and the Yacht Club. Now, at the end of its 70th anniversary, it needs to be resurrected and remembered for the incredible bravery and defiance shown by the ratings, all young men between 17-24 years old, who dared to face the might of the British Empire and played a major role in the British advancing the date for the transfer of power.

Few can believe that for an incredible five days, these ratings (enlisted members of a country's navy), took over the naval ships moored in Bombay harbor, took down the British flags and replaced them with Indian flags, and had the British Empire in a panic, with flurries of telegrams to Whitehall, furious debates in the House of Commons and House of Lords, panicky requests for reinforcements and battle ships ordered to sail to Bombay from nearby ports. Inspired by the heroism shown by the ratings, Bombay citizens poured out onto the streets in support, burning and looting British-owned shops.

The saga began on Navy Day, December 1, 1945, when a group of ratings belonging to HMIS Talwar, a shore establishment (now Badhwar Park) in the naval dockyard area in Bombay, decided to test their resolve and commitment to challenge the British naval forces in India. They were inspired by the charged political atmosphere and, in particular, disturbing reports from the INA trials taking place at Delhi's Red Fort. The initial group, calling themselves Azad Hindi, consisted of around 20 ratings and the first phase of their plan was to strike work. They were enough reasons to do so, starting with the humiliating mass demobilization of Indian naval personnel after World War II, despite the heroism and sacrifice they had displayed while fighting alongside British and Allied forces. There was also the supercilious treatment by British officers, discrimination against Indians in living conditions, and the poor quality of food they were served on a regular basis.

December 1, 1945, was the ideal day to literally test the waters. It was to be the first time in the history of the Royal Indian Navy that civilians had been invited to board the naval ships and shore establishments to witness the pomp and ceremony. The minute preparation for the ceremony was over and the British officers left, the Azad Hindis got busy. The next morning, HMIS Talwar the shore establishment in Colaba Bombay, was littered with torn flags and slogans like 'Quit India,' 'Down with the Imperialists' and even 'Kill the British' were painted in large type on the walls of the barracks. The British were naturally enraged but no arrests were made due to lack of evidence.

But who were these brave young men? One was Telegraphist RK Singh, who was inspired by Subhash Chandra Bose but believed in the Gandhian principle of open defiance and was the first to submit his resignation as a mark of protest. In the defence forces a soldier can be dismissed, relieved or given premature retirement. Singh insisted on resigning. He was summoned to the office of the Flag Officer Bombay, (FOB). There, he argued with his seniors, threw his Royal Indian Navy (RIN) cap on the floor and kicked it. As a mark of disrespect to the crown and the British Raj, it was the ultimate crime. He was immediately arrested and sent to Arthur Road jail in Bombay. His named was promptly removed from navy rosters. Neither does he find mention in the history of the freedom movement in India, even though his act of defiance was no less than any freedom fighter.

His action inspired Lead Telegraphist Balai Chandra Dutt, 22, who had left the comfort of a Bhadralok family in Bengal to join the navy. Dutt would play a leading role in the events of February, 1946, which was when the other ratings staged their mutiny. On February 2, the visit of Flag Officer Commanding, Royal Indian Navy (FOCRIN), was announced. He was scheduled to visit HMIS Talwar, the second biggest signal school for the navy across the British Empire. Despite the extra security, BC Dutt who was on duty between 2-5am, managed to write seditious slogans like 'Quit India' and 'Jai Hind' and paste pamphlets below the dais erected for the occasion. He was caught with a bottle of gum and chalk in his hands and seditious literature was found in his locker. He too was arrested but his action made him a hero to the 20,000 ratings who joined in the uprising that would rattle the British Empire.

On the night of 6/7 February, Azad Hindis deflated the tires of the car belonging to their commanding officer FW King, and scrawled the same slogans on the paintwork. Commander King flew into a rage on seeing his car and stormed into the barracks. Defying naval custom, none of the ratings stood up or saluted. Seeing this, he shouted 'Get up you sons of coolies, you sons of Indian b***hes, Sons of bloody junglees' . It was the last straw. From now, the mini-revolt would gather steam and become a full scale uprising or a Mutiny in military terms. On the morning of 18 February, Azad Hindis joined by a large group of ratings on HMIS Talwar, refused food and declared a hunger strike. Being telegraphists they relayed the news immediately. Within no time, the news of their defiance reached all ship and shore establishments around the major ports of Bombay, Karachi, Visakhapatnam, Madras, Calcutta, Thane, and as distant as Bahrain, Singapore and Indonesia.

Eventually, the uprising would involve 20,000 ratings, 78 ships and 20 shore establishments. The British were taken by surprise and before they realised the extent of the mutiny, the brave young sailors had taken control of the armoury on most of the ships and establishments, forced the officers, mostly British, to beat a hasty retreat, pulled down the British flags from all the ships and replaced them with flags of the Indian National Congress, Muslim League and Communist Party of India. Having gained control of the ships, they pointed the ship's guns at the Yacht Club, Gateway of India and the Taj Mahal hotel, buildings that signified the pride of Britain in India. They used this as collateral against any possible use of retaliatory force by the British.

In the course of a few days, they had the British authorities on the run. For one entire week, Bombay resembled a city at war. Hundreds of civilians joined in, leading to widespread loot, arson and even deaths. Mill workers united with railway workers to bring the city to a grinding halt. The British rushed in troops and additional forces with mixed results. Asked to open fire on the mutineers, soldiers of the Maratha brigade refused. The British used other forces to fire on the ratings, and it led to close to 300 deaths. This was now a full-fledged mutiny and inevitably, political intervention would be required.

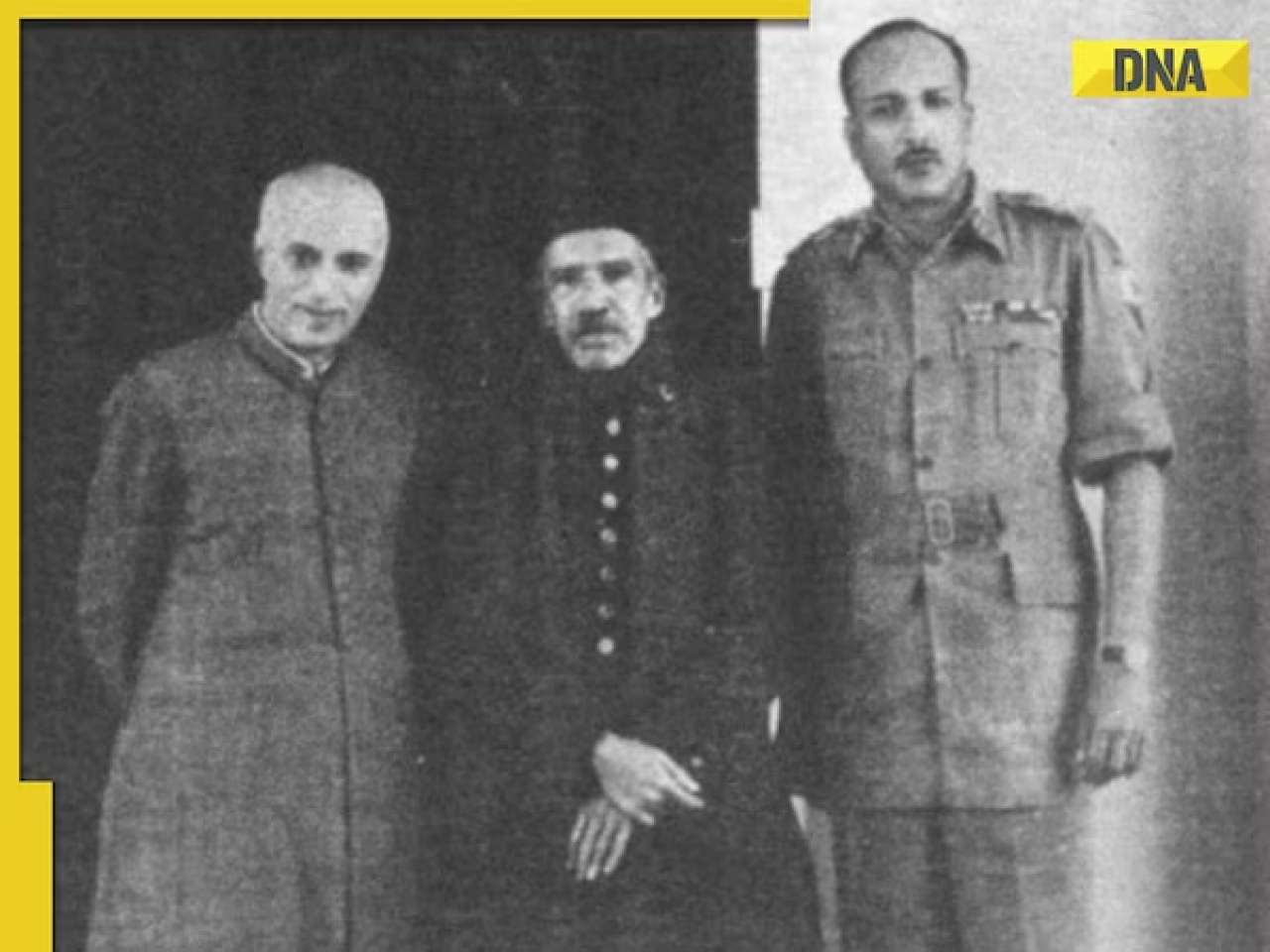

The politicians were divided on the issue. The Communists supported the mutiny. Independence activist Aruna Asaf Ali addressed the ratings and pledged support. The Congress saw some disagreement on the issue between Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel. Nehru initially supported the mutiny and arrived in Bombay against Patel's wishes and met the ratings. On the other hand, the Muslim League under Jinnah appealed to Muslim ratings to abandon their strike. Gandhi was totally opposed to the mutiny and put Sardar Patel in charge of sorting out the issue.

It was hotly debated in the council house (Parliament) in Delhi and the tremors reached Westminster in London. There were angry exchange of telegrams between offices of Prime Minister Attlee and the Viceroy of India Lord Wavell. The British government ordered seven ships including HMS Glasgow, its most powerful warship in the Indian Ocean to sail full steam from Trincomalee in Ceylon to Bombay to crush the mutiny. Admiral Godfrey, head of naval forces in India, threatened to destroy the Royal Indian Navy. Royal Air Force made threatening sorties over the Bombay harbour.

On Gandhi's advice, Patel invited the newly formed Naval Strike committee lead by senior Telegraphist MS Khan and Madan Singh for discussion. Talks went on for several hours and Patel assured them that there would be no victimization. The Strike committee met with the ratings to discuss the terms. All night they argued, disagreed and shouted at each other and eventually wept like children. At 6am on February 23, the senior ratings carried white flags to their respective ships as a signal of surrender. Many had tears in their eyes yet they held their heads up high. They had composed a surrender document the last few lines of which read: "Our strike has been a historic event in the life of the nation. For the first time the blood of the men in services and the people flowed together in a common cause. We have not surrendered to the British. We have surrendered to our own people. We in services will never forget this." The surrender document was said to be drafted by Mohan Kumarmangalam, the Communist leader.

The denouement was tragic and a blatant betrayal of the promises made by the politicians. Almost 1,000 ratings were arrested and sent to various camps, a few were given jail terms. A majority were escorted to railway stations, handed a one way ticket and sent home for good. Gandhi said about the mutiny: "…they (ratings) were thoughtless if they believed that by their might they would deliver India from foreign domination." BC Dutt, the hero of the uprising, would later write a book on the subject and in the last chapter, he writes: "The aftermath of a revolution is determined by the enormity of the change affected by it. The Indian revolution is itself an example, for despite the presence and influence of Mahatma Gandhi, blood did spill."

Pramod Kapoor is Founder, Publisher, Roli Books. His book '1946: The Unknown Mutiny' will be published later this year.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

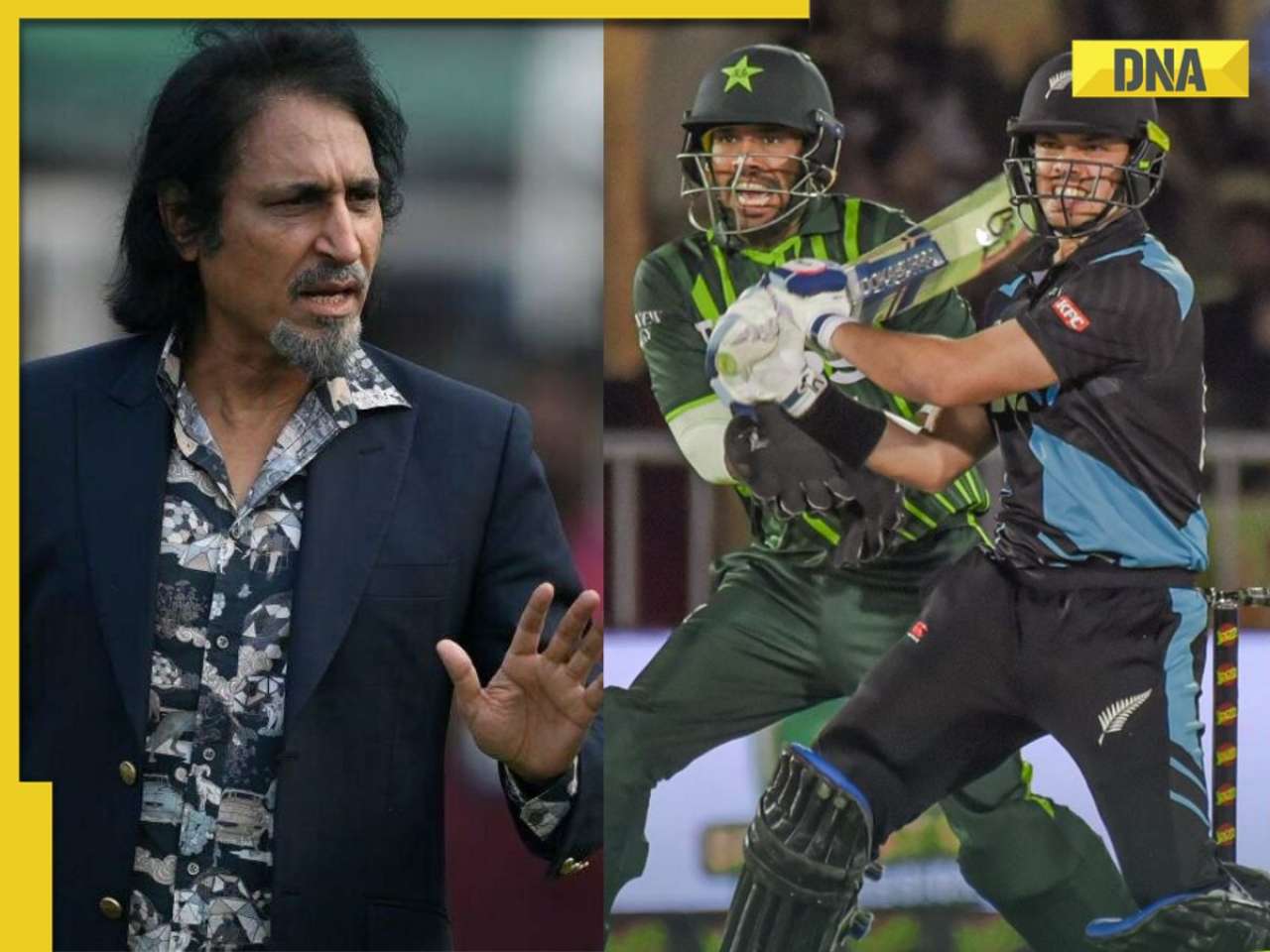

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

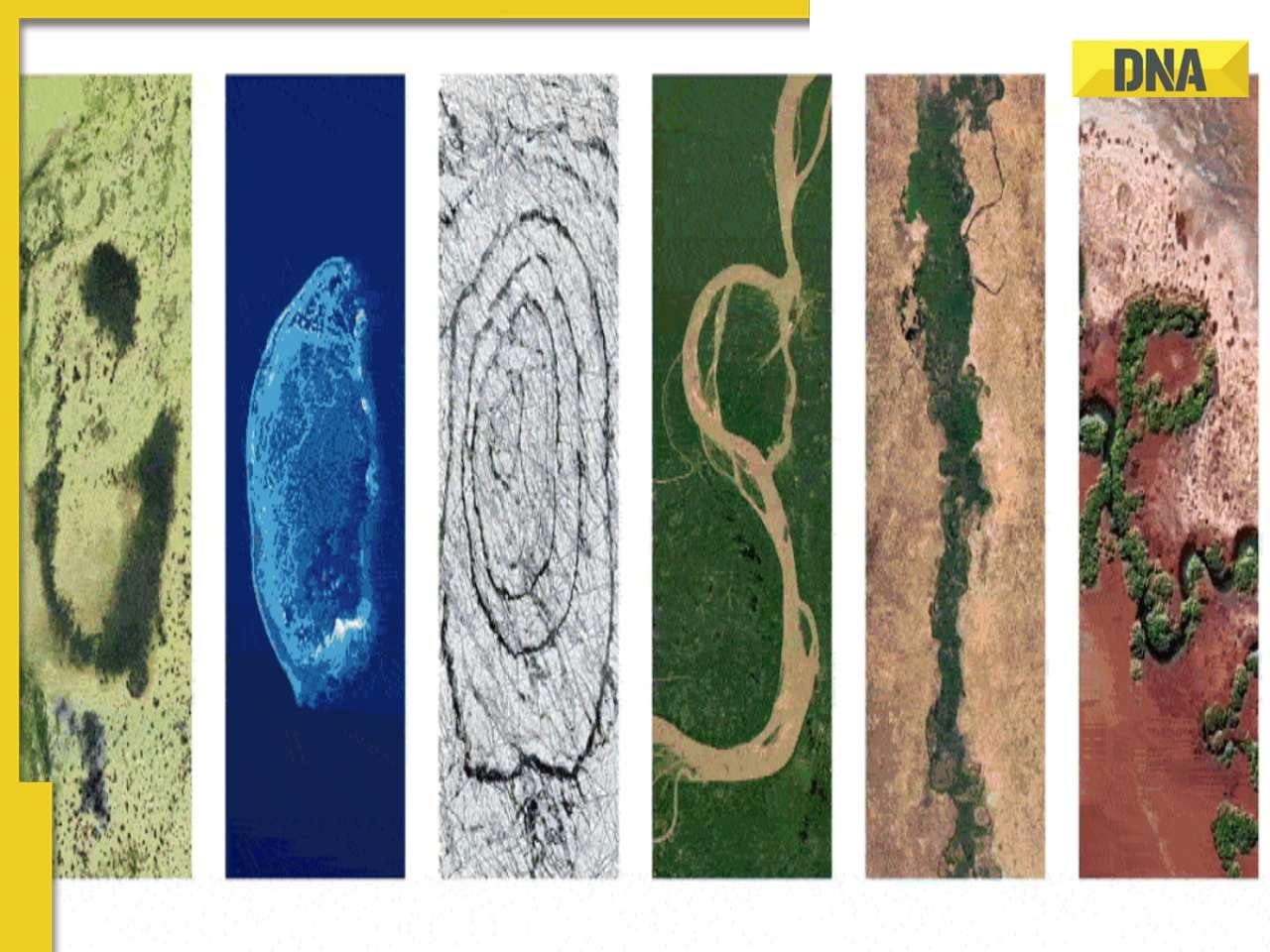

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)