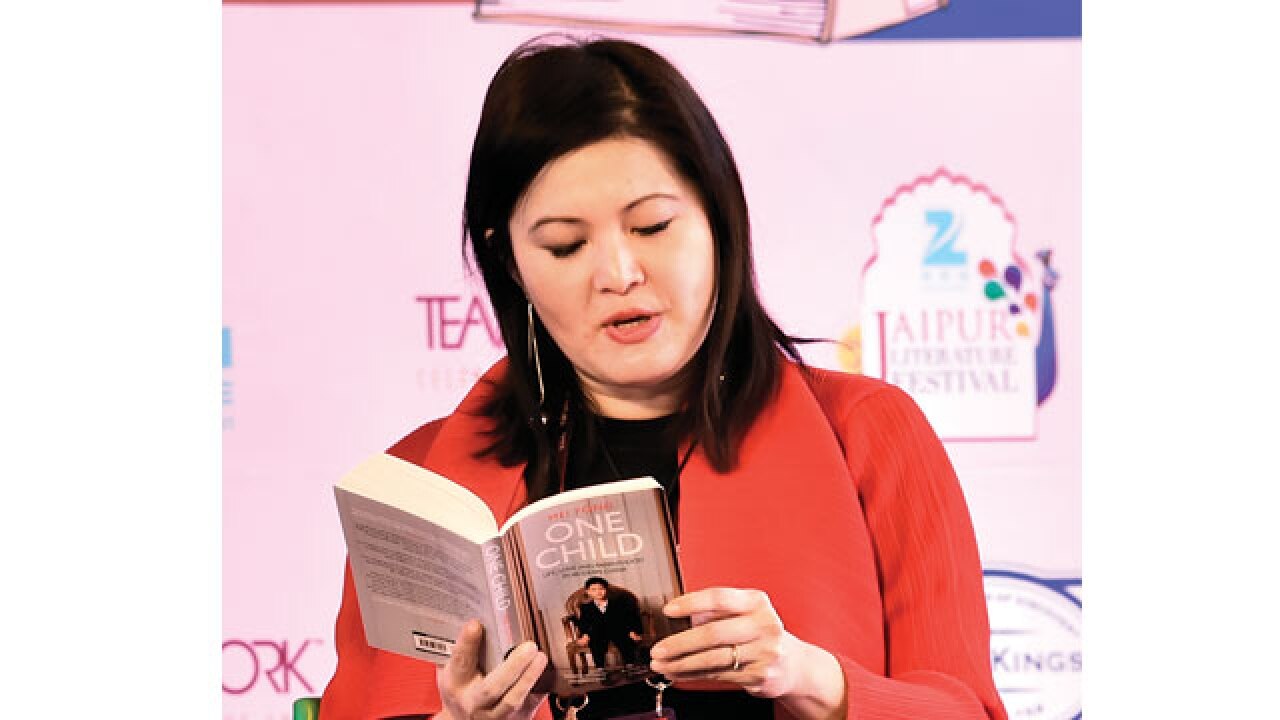

Pulitzer Prize winner Mei Fong's One Child: The Story of China's Most Radical Experiment hit the stores just around the time the Chinese leadership announced reversal of its one-child policy in October 2015. The Malaysian-Chinese-American journalist's 2015 book is a trenchant critique of the government's disastrous social experiment that left the population, particularly women, scarred and disillusioned. Edited excerpts from an interview:

One of the most enduring impacts was few males and fewer females. After 30 years of one-child policy, you have 30 million men, which is about the population of Canada, and not enough women.

The second impact was China's big greying population. By 2050, the senior population would be bigger than the population of Europe. It's not exactly the function of the one-child policy. The problem is the size of the working-age population to support senior citizens is much smaller.

China may be the world's second largest economy in terms of size, but in terms of per-capita GDP basis, it's lagging behind Scandinavian countries. China is going to get old before it gets rich. There will be more people enjoying retirement benefits than those working.

It had affected women at many levels. There were forced abortions. There were women who wanted children and had to give them up. In some cases, the children were shipped abroad for adoption.

It isn't going to be easy. The government is exploring the possibilities of increasing more benefits for couples going for a second child, but nothing to the level that we see in Scandinavian countries. To increase birthrates, China would have to undertake some very expensive measures, and its economy can't afford that. We have to keep in mind that falling birthrates is a global trend.

I was a correspondent in China and Hong Kong for about seven years, and after leaving the Wall Street Journal, I spent three years researching for the book.

I can't get a Chinese publisher because censorship in the last four years has been particularly tight. Those people who can publish it in Hong Kong and Taiwan in Chinese language are equally scared because of what happened last year in Hong Kong – a series of kidnappings of booksellers. When I realised I wouldn't be able to get a Chinese publisher, I decided to commission a translation into Chinese and release the book on the Internet in PDF (Pre-Download Format). I did it deliberately because I didn't want the Chinese authorities to trace the download back to the readers.

I spent $10,000 for translation. To cover my costs, I have put up a virtual tip jar via crowdfunding platform GoFundMe. Another real cost is I wouldn't be able to go back and work in China. The authorities won't let me.

I want to encourage more authors to take to self-publishing. If your stories are real and true and important, you just can't sit back and wait for things to happen.