I think recipe writing has become formulaic and over-concerned with timings for frying onions or amounts of parsley when really, these should encourage people to trust their judgement, taste and see how long it takes and how much you need. They should tell them how to smell and taste and look at the colour," says food anthropologist and writer, Claudia Roden.

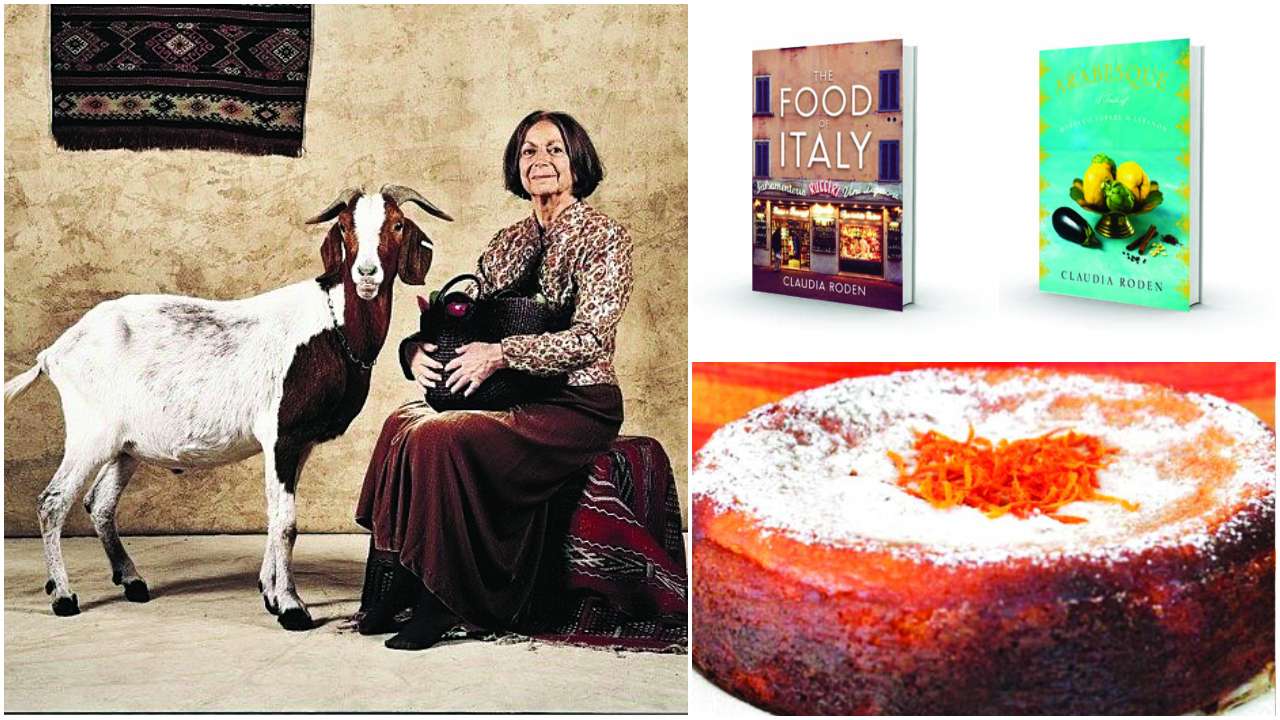

Roden should know. After all, the 83-year-old Cairo-born London-based has authored 20 cookbooks; her first was out in 1968, and her next will be out soon. This authority on Mediterranean and Middle-east cooking is known for her documentation of recipes that include the origin, history and evolution of the dish, anecdotes around it, and method of serving or eating it. She's won six Glenfiddich awards, Premio Orio Vergani (Italy), Versailles Award (France), and Prince Claus Award (Holland) for cultural achievement, was inducted into the Cookbook Hall of Fame by the James Beard Foundation, among other laurels.

But Roden's career goals were never about food. Understandably so, as the women of her rich Syrian Jewish merchant family never cooked. She became Egypt's backstroke swimming champion at 15, schooled in Paris and then at London's Saint Martin's School of Art vying to become the next Diego Rivera – Frida Kahlo's painter-muralist ex-husband. Then President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal, he banished the Jews and the whites, including Roden's parents, who fled to London to join her in 1956. Roden had to trade her art dreams for a job at the airlines.

Her parent's home became a pit stop for exiles from Egypt, Iran and Turkey before they made a fresh start elsewhere. These exiles would often compare recipes, evaluate who cooked it better back in the motherland they could no longer return to. Salivating at memories was their only succour.

Moved by their tales, she began asking them for recipes and wrote them down. In fact, her sister-in-law's grandmother, then visiting from Italy, gave her the first recipe, which is now world-famous and synonymous to Roden. It's a Sephardic [from Spanish Jews] orange-and-almond-cake; a moist, flourless dessert made from juicy oranges pureed whole with their peels and seeds. To it, Roden, at times "adds a tablespoon of orange blossom water and serves it with orange slices or a scented whipped cream."

In time, Roden fashioned into a serial recipe-collector, a willing recipient of dying/to-be-lost food traditions. "For decades, wherever I went researching for food, I made a point of asking everyone I met what their favourite food was and how they cooked it. I have discovered many new ways and little tricks, especially by watching people cook."

One highly amusing trick told to her, which she told 'The New Yorker' in a 2007 interview, was the accurate way to measure flour: 'Press your earlobe. See how it feels. When the dough feels like your earlobe, it's the right consistency.'

While it's easy to pile on the lard in a profession like hers, Roden, at 83, is thin, sprightly, with her kohl eyes still wide and curious. Shunning latest trends is a major reason. Her second secret is her own writing, which is why she consumes a lot of fruits, vegetables, pulses, grains and nuts, also fish but little meat. "Writing about food has affected my eating habits. I mainly write about the cuisines of Mediterranean countries so I use mostly olive oil instead of butter for cooking, although I have not cut out butter when it is important in a dish. It's important to have variety because ingredients have different nutrients and vitamins and you should aim at having as many as possible," she advises, sagely.