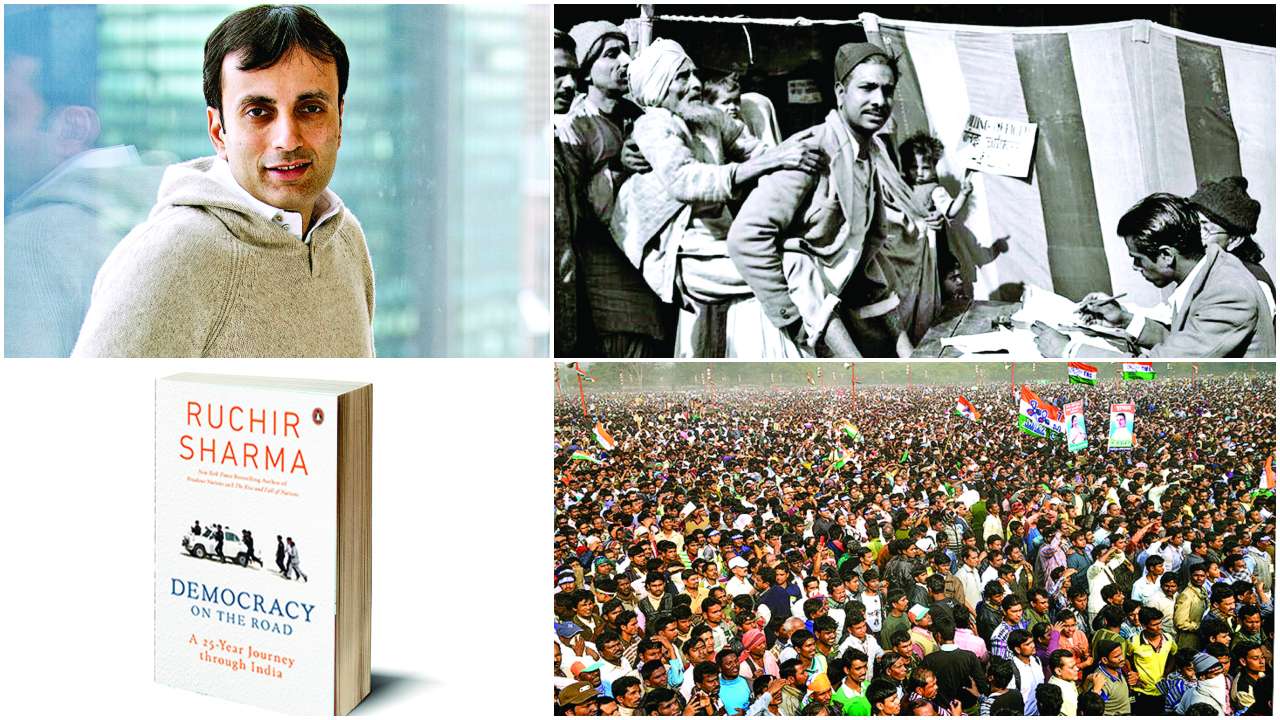

Book: Democracy on the Road: A 25 Year Journey through India

Author: Ruchir Sharma

Publisher: Penguin Allen Lane

Pages: 352

Price: Rs 699

Indian investor Ruchir Sharma has previously written the Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of change in a Post-Crisis World, and Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles. Money and economics apart, Sharma takes a keen interest in Indian politics. As a young boy, he spent his early years in the small town of Bijnor in Uttar Pradesh, which is “by far the most political state of India”. Having been on the road throughout the country across constituencies chasing election campaigns for more than two decades, Sharma wrote Democracy on the Road on the eve of the landmark general elections to offer an “unrivalled portrait of how India and its democracy work”. Edited excerpts from the interview:

I think that the caste lines run deep in our country. In the last few years, polarisation has increased. Now, it has become even more difficult to have a reasoned debate with two sides of some issues. I’m asked what issues will dominate the election, but fact is I’m not sure if they will at all because people will vote the way they want to. Voting blocks are quite secure along caste and religious lines.

They are necessary, but not a sufficient condition to win the elections. You need to get that equation correct to win. I mention towards the end of the book that there are about six factors or so that determine an election. [For instance] U T Khader, a local politician from Mangalore, made an insightful comment saying that winning an election in India is like passing a series of six tests. And you need a minimum scoring grade of 35 per cent each. That’s how difficult it is to win an election in India. There are six parameters: caste and religion, family connections, how much money you’re spending on the campaign, the welfare schemes you have introduced, what is your perception as far as corruption is concerned, and then development.

Unfortunately not. Winning an election in India on the basis of development is very difficult, if not impossible. Elections here are hard-fought and winning them on the back of development is just a hassle in this country. Yes, there are places where development has made a big difference such as Bihar (a state where development played a big role in the last 10 years), but it is one of the six factors that help you win or lose an election. Because even in a place like Bihar, which is arguably the most transformed state in this country, Nitish Kumar cannot win an election based on just development – and needs a caste coalition – because his [party’s] vote share never really goes beyond 20 per cent. His own personal vote share is only 3-4 per cent of the caste that he belongs to: the Kurmis – even for someone like Nitish Kumar, who is the most transformational CM possibly in this country in terms of what he has achieved with his 10 years in Bihar.

If you introduce a welfare scheme for one community, the other communities begin to feel left out. So one of the insights that were offered to us was by leader Kamal Nath, when we met him last year, was that if you do a welfare scheme, it needs to be done for everybody but if you do it for a particular community, everybody else begins to feel left out. And then there is the whole issue that I address very extensively in the book is that we keep announcing one welfare scheme after another, and now we have more than a 1000 schemes and how these schemes ever tend to work? Because final [intended] person doesn't get as much benefits as was promised initially. For instance, a minimum support price a farmer is supposed to get, doesn't get that minimum support price because of the fact that the state bureaucrat or the person from the FCI from whom he goes to collect the minimum support prices gives him a big runaround; if he goes to deposit a cheque, it is not encashed in time.

I end the book on a very optimistic note: basically saying why democracy is thriving in India compared to other countries in the world. Despite the fact that the odds may be against you – the ruling party may seem to have more money power, media power and/or better organisational skills – the fact that we’re having such a competitive election and that the opposition, in the last one year, has been able to mobilise its resources and galvanise the truth, is a very telling statement about this country and how things function. The opposition has been able to galvanise itself and use its power given how competitive this election is shaping up to be.

The importance of coalition – that’s the reality of India. If you trace the history of Indian democracy, every time one leader gets too powerful, the opposition typically tends to galvanise against him. That’s a reflection of this country’s nature, culture, DNA – whatever you want to call it. Because in 1977, the opposition came together to unseat Indira Gandhi. The same thing happened again with Rajiv Gandhi after his landslide victory in 1984. Then against Vajpayee in 2004 when the alliances came together.

Expectations are always going to be unrealistic in terms of how things were. In this country, leaders are much more effective at a state level than at a national level.

In India, the greatest transformation has happened at a state-level. You basically have a dynamic leader who has worked for the state. In fact, even Modi when he was in Gujarat, Nitish Kumar in Bihar, Sheila Dixit in Delhi, Shivraj Chauhan in Madhya Pradesh: they all lost eventually [except Modi], but you can argue that for 10-15 years, they did a lot for the state in terms of the transformation that they had done. I feel it benefits the citizen when you have more devolution of power to the state, so they can carry out their reforms.

It is shaping up to be a super competitive election. A year ago, it seemed like Modi coming to power was a mere certainty. Today, there has been a dramatic change in that. Modi may still come back, maybe the BJP might come back but with a different leader, or maybe the Congress-led government like 2004. I will be coming back for my 28th election trip in April to try and find that out.